Essay: #EndFGM

To write about Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C) for more than 30 years, as I have, is to invite all manner of fools and fuckery.

From my Egyptian compatriots who will spend more time denying the veracity of figures that say 87 percent of girls and women aged 15 - to 49 years in our country have undergone FGM/C, than asking why we still subject our girls to such brutality. With a population of nearly 100 million, that horrific percentage means that Egypt has the greatest number of women and girls who have experienced FGM/C of any country in the world.

To white women who are more horrified at FGM/C in my country of birth than other manifestations of patriarchal fuckery on their home turf because “saving” women somewhere far away is much easier of course than saving yourself by fighting like hell at home, e.g. the woman in Texas, the state which has now banned abortion, who asked me how she could help women in Egypt fight FGM/C.

To the cultural relativists who diminish or deny the danger and harm of FGM/C–and in so doing, also deny and diminish the tireless anti-FGM/C work of activists in Egypt and other countries where cutting happens–because they want to “protect” us from racists and Islamophobes, who in turn see misogyny only in non-western countries and who insist it is the sole property of Muslims, refusing to believe that in Egypt Muslims and Christians alike subject their daughters to FGM/C.

I do not write for them. I do not write for their ire or approval. I do not write for their conviction or their conversion. Fuck each and every one of all of the above.

87 percent of girls and women aged 15 - to 49 years in our country have undergone FGM/C. With a population of nearly 100 million, that horrific percentage means that Egypt has the greatest number of women and girls who have experienced FGM/C of any country in the world.

I write for the women I love who at the age of eight or nine were brutalized and butchered as their own mothers watched, sometimes helping to hold them down. Can there be a greater betrayal? And in the name of love! Yes, love. For those mothers do not hate their daughters. They have not forgotten being brutalized and butchered as their own mothers held them down. How could they? Nor the pain. But they understand, as their hearts smash to pieces, that patriarchy has deemed that without such butchery their girls are impure, sexually out-of-control, and unmarriageable. And so they cut away to make them complete. The irony of cutting, of mutilating, to make whole.

Egyptian feminist Nawal El Saadawi, who died last year, recalled her cutting at the age of six:

“I did not know what they had cut off from my body, and I did not try to find out. I just wept, and called out to my mother for help. But the worst shock of all was when I looked around and found her standing by my side. Yes, it was her, I could not be mistaken, in flesh and blood, right in the midst of these strangers, talking to them and smiling at them, as though they had not participated in slaughtering her daughter just a few moments ago.”

How does a girl who survives the barbarism of that cutting survive with her trust of anyone intact, especially after her own mother did not protect her but was there as a part of the pain? The trauma, the pain and the life-long consequences of having a part of or all of the external and visible part of the only part of the body designed purely for pleasure––the clitoris– all to appease that god of virginity.

In Egypt, most girls are subjected to type 1 and type 2 forms of FGM/C.

We hack away at perfectly healthy parts of our girls’ genitals because we’re obsessed with female virginity and because women’s sexuality is a taboo.

I first learned about FGM/C from a news article when I was about eighteen, soon after which I was told that many women of my extended family had been subjected to the horror when they were girls. My world came apart.

I was worried sick that I’d been cut and had somehow buried the memory. I checked my genitals in panic, not really knowing what would have been missing had I been cut, but worried nonetheless.

I have not been cut. I have spent the past 35 years obsessed.

Soon after I learned what the practice was,, what I can only describe as destiny led me to Dr Nahid Toubia, the first woman surgeon in her native Sudan and an anti-FGM activist. I was then an eager young feminist but I was unable to find the words to describe how heartsick I was that so many of the women I loved had been violated as girls through genital cutting.

Dr. Toubia helped me find the words. She would tell me about her delicate discussions with her own mother about her mother’s FGM/C, and when I asked her how I could be as delicate in my own conversations, she told me never to make the women we love feel like “freaks” for having been subjected to cutting.

Something that hurts so many girls and women is kept silent and taboo because it has to do with our genitals and with sex. The biggest obstacle in the global fight against FGM is the reluctance to talk about the practice and the ways it harms girls and women–physically and psychologically.

There is a scene in Egyptian novelist Sonallah Ibrahim’s “Zaat” in which the protagonist, the eponymous Zaat, a middle-class Egyptian woman, narrowly flirts with subjecting her daughters to genital cutting at her mother’s insistence. Zaat discusses her misgivings with her best female friends who dissuade her, reminding her of how their own cutting had ruined their sex lives with their husbands.

Why aren’t more mothers saying that? Why aren’t more women writers saying that loud and clear? Why does it take a male writer to remind women that our society is denying them the right of pleasure?

Because patriarchy gives men the power to decide if we deserve pleasure or not.

It is our right to enjoy sex. We have a right to pleasure. We own our desire and we have a right to express it freely. We must end FGM/C.

Egypt first banned FGM/C in 1959, and then permitted it again in some forms. When Egypt hosted the 1994 United Nations Population Conference, it was embarrassed by a CNN report that showed a cutting procedure, despite official claims that it was no longer practiced. The government then allowed “medical” genital cutting — in which the procedure is carried out in a medical environment or by a medical professional — until 2008, when a universal ban was imposed after a 12-year-old girl died the previous year during a procedure in a clinic. It seems we pay attention only when female genital mutilation kills a girl. Otherwise, we quietly ignore it.

In April 2021, Egypt toughened penalties for FGM/C, imposing prison terms of up to 20 years in a push to end the practice.

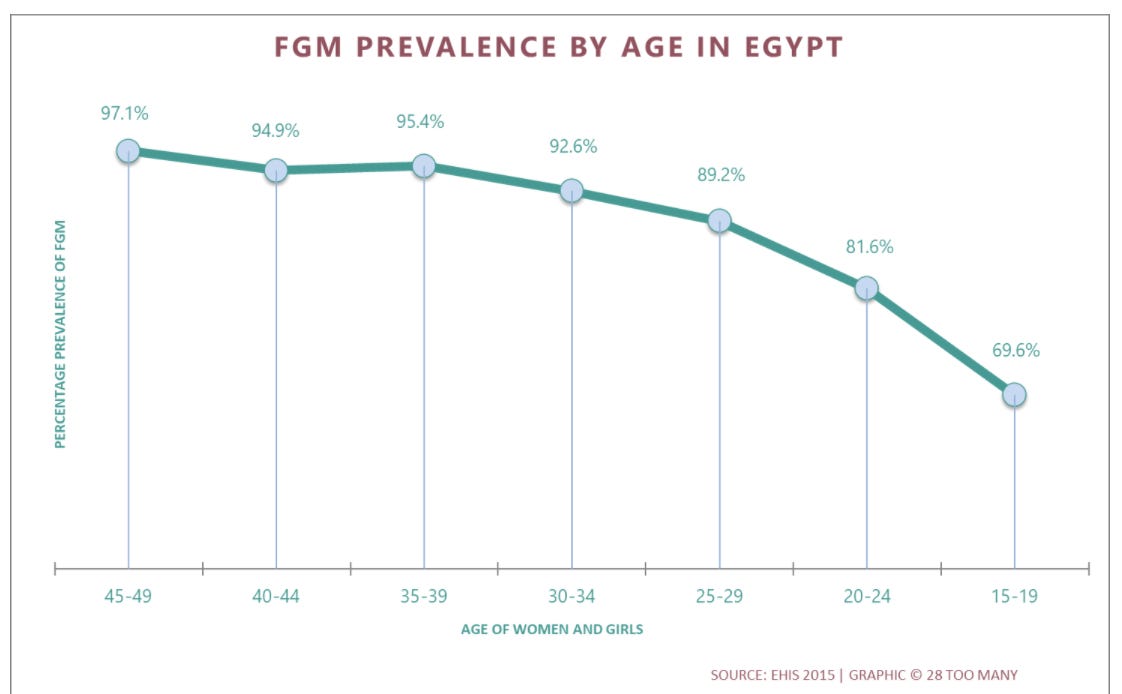

But still it persists. Has it decreased at all? At a tenaciously slow rate. A secondary analysis of data on Egyptian girls aged 0-17 between 2005 and 2014 concludes that the total percentage of girls who had already undergone FGM/C and those who were likely to undergo FGM/C before they reached 18 years of age fell from 69% to 55% in that period.

Breaking down the most recent data by age group shows that the prevalence for women aged 45-49 is 97.1%, while for the youngest age group this has fallen to 69.6%.

Because Egypt’s anti-FGM/C laws were seen as a result of international pressure, it created the appearance of an onslaught of neo-colonialism and racism againt tradition and culture–the bodies of women and girls, as always, serving as a proxy battlefield. That is the minefield that local anti-FGM/C activists must traverse. They have worked tirelessly for decades at an almost Sisyphean task.

What is especially alarming is the “medicalization” of FGM/C, in which the barbarism of the practice is whitewashed by the “respectability” as well as legitimacy from its being carried out by trained medical personnel. More than 75% of genital cutting in Egypt is performed in a clinic by medical personnel.

When I interviewed a 53-year-old survivor of the practice in Cairo for a BBC radio documentary in 2014, she told me, “It must be carried out, because that’s the way to maintain the purity of girls, to make sure that the girl is not out of control. We don’t care if it’s against the law or if they’re trying to stop it. We know doctors who are willing to continue and have done so.”

Laws are not enough. We need nothing short of a sexual revolution that centres our pleasure and liberation; a recognition that it is not enough to stand up to the State alone, as we did during our revolution in January 2011. We must stand up to patriarchy too. At the heart of any revolution are consent and agency, the unequivocal belief that I own my body–not the State, not the Church/Mosque/Temple, not the Street and not the Family. If is from that belief that we can all help in the fight against FGM/C by talking openly and unashasmedly about sex and our bodies, as these sexual radicals and revolutionaries have begun to do.

Sharing our stories is often the only way we get answers to things we’ve been too scared to ask. Once, during a conversation about FGM/C in Egypt that I intitiated with a consciousness raising group I led in Cairo ahead of February 6–the International Day of Zero Tolerance for FGM/C–a thirty-five-year-old woman asked me a question that was heart crushing in its simplicity.

“Am I normal? Will I be able to enjoy sex?”

Her cutting was done to her when she was eight at the behest of her grandfather and without the approval or knowledge of her mother, who was not at the house at the time.

I told her that the clitoris was like an iceberg, with the majority of the nerve endings deep in the body and not in the glans. I understood from her question that she had not yet been sexually intimate with another person and I told her that I hoped when the time came, it would be with a patient partner for whom her pleasure was important.

Today, I would also urge her to consult with Restore FGM, the first treatment centre for survivors of FGM/C in Egypt and the Middle East.

“We opened this center because we realized the demand,” Dr. Reem Awwad told France 24. “We have approximately 40 million women in Egypt who are victims of FGM and who have nowhere to seek treatment.” The center offers genital restorative surgeries, non-surgical therapies and psychotherapy.

And today, I vow to her and the 200 million women girls and women in Egypt and around the world who are survivors of FGM/C, that I will always fight to ensure that we, not patriarchy, own our bodies. Girls and women are forced to be cultural vectors; our bodies are the medium upon which culture is engraved–FGM/C is one of the earliest violations imprinted on the female body. And yet we are too often barred from authoring that culture that marks us.

Every day–not just this one day when we urge the world to remember yet another way that patriarchy hurts us–I will fight to ensure that we claim ownership of our bodies; no longer vectors, but authors of our liberation. And I honour the heroes of our liberation, such as these fellow African activists whose lived experience is vital.

It is our right to enjoy sex.

We have a right to pleasure.

We own our desire and we have a right to express it freely.

We must end FGM

Mona Eltahawy is a feminist author, commentator and disruptor of patriarchy. She is editing an anthology on menopause called Bloody Hell! And Other Stories: Adventures in Menopause from Across the Personal and Political Spectrum. Her first book Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution (2015) targeted patriarchy in the Middle East and North Africa and her second The Seven Necessary Sins For Women and Girls (2019) took her disruption worldwide. It is now available in Ireland and the UK. Her commentary has appeared in media around the world and she makes video essays and writes a newsletter as FEMINIST GIANT.

FEMINIST GIANT Newsletter will always be free because I want it to be accessible to all. If you choose a paid subscriptions - thank you! I appreciate your support. If you like this piece and you want to further support my writing, you can like/comment below, forward this article to others, get a paid subscription if you don’t already have one or send a gift subscription to someone else today.