What do we do with our restless hearts in these days of pandemic-induced lockdowns? Is there such a thing as nostalgia whereby we long not for a “normal” that advantaged only the few and fueled the inequalities that have made the pandemic a fucking disaster for the many, but for the times in our lives which stretched and strengthened that muscle we call our heart? I want to call it my feminist nostalgia.

What from the Before Time do we celebrate? Which of our memories make that muscle we call our heart remind us that it is not just blood that keeps us alive, but the song of love it conducts in our ears, multilingual, polyphonic.

Talking to my parents on the phone echoes that song. They speak to my siblings and me in Arabic and we reply in English. My parents, siblings and niblings - a gender-neutral term for nieces and nephews that I have learned from the great activist adrienne maree brown - were last together in November 2019. I miss them all terribly. That missing them, that longing for a loved one, is a leitmotif for my family.

And we have an anthem for it that filled our weekends in London back in the 1970s with nostalgia and longing so delicious, the high was sharper than anything sugar could deliver. It was a high reserved for the weekend, when my parents pressed play on a cassette tape of Abdel-Halim Hafez songs to stay connected to the country they had just left behind at 31 years old. One song in particular has always stayed with me. Sawwah.

I don't know and I struggle to imagine what it would feel like to have been born in a place, to grow up in it, to be educated in it, to begin your career in it, and where all your family and friends are, and then to leave it when you are 31 years old for a country you have never been to so that you can study for a PhD in a language you are just learning, with two young children 7 and 3 years old in tow.

My parents were on Egyptian government scholarships. They were not refugees uprooted by war or disaster or political persecution. To leave everything that makes up your world because you fear for your life is exponentially harder of course. I honour that.

I am thinking of another kind of exile; the exile of the heart.

Sawwah roughly means the wanderer. Someone who wanders, roams, is set adrift.

A refrain in the song has Abdel-Halim - or Halim as he is known - imploring "If my beloved finds you, tell me how he's doing. Tell me what is that foreign land (ghorba; another word deep with associations, meaning strange, foreign, weird) doing to the brown-skinned one."

I have known foreignness most of my life. My parents knew a rootedness I have never experienced. And Sawwah is a song addressed to them and others like them, wandering so far, with their roots so exposed, so vulnerable. In a strange land. In exile of sorts, exile of the heart, albeit a voluntary exile wherein your children remind you that you are in that strange land, the ghorba, every time they speak to you in the language of that foreign land, which they learned so easily, and which replaced the language of your homeland so quickly.

Will we shake in joy and excitement when we can embrace again, post-pandemic? Are we ready for how overwhelming that moment of reunion will be?

Very soon after we arrived in London, my brother and I became fluent in English, in the way that young children absorb language like a sponge, innit? Our parents wanted us to remember Arabic and so would always speak to us in Arabic, a tradition which continues to this day.

We used to send cassette tapes to my grandparents back in Egypt because international phone calls were so expensive in the 1970s. Many years later, going through boxes at my grandparents’ home in Cairo, I once heard one of those tapes. As I marveled at the younger voices of my brother and me, rambling on about what we had done that week in our round London accents, I did not know if my grandparents understood a word of what we had said but I was sure they missed us and missed watching us grow up. And that too is part of ghorba.

And isn’t that what we all feel today - the ghorba forced on us by the pandemic?

We had lived with my paternal grandparents for 6 months while my parents settled in London. And then my brother and I left our grandparents and Cairo in June 1975, wearing almost our entire winter wardrobe because everyone was sure that London was freezing cold. England is cold and damp, right? We arrived to find it in the middle of one of the worst heat waves in years.

My brother was so excited to see our parents he was shaking. Just like he used to shake when our dad would return to Cairo from the military camp where all the doctors had been mobilized in Egypt in 1973 during the war with Israel. Sawwah was all of that. Shaking in excitement at being reunited with a loved one. Hearts in exile going home.

Will we shake in joy and excitement when we can embrace again, post-pandemic? Are we ready for how overwhelming that moment of reunion will be?

Now, I feel at home when I miss something, when I am roaming. I am at home in longing. When I was in Cairo, I missed New York City. When I am in New York City, I miss Cairo.

Sawwah the song is shorthand for my parents missing Egypt, missing their families and friends, missing who they were in Egypt and figuring out, caring for, nurturing who they were becoming in London.

“Tell me, how is life in the land of strangers (ghorba) treating my brown-skinned one?” Halim would ask. I imagined him asking about my parents, and at the same time, I learned to always miss something and roam, perpetual exile.

When I returned to Egypt 14 years later at the age of 21, I understood.

One day sitting in a taxi stuck in Cairo traffic, the opening chords of Sawwah came on the radio and I could barely see from the tears. It was as if my parents were there in that cab with me, pressing play on the cassette player of my exiled heart.

Now, I feel at home when I miss something, when I am roaming. I am at home in longing. When I was in Cairo, I missed New York City. When I am in New York City, I miss Cairo. There must be one of those famed German words for that feeling. I love the word Saudade, that feeling of longing, melancholy, desire, nostalgia; to yearn for something that has passed, never even existed, when you miss something you have never known. This is different. I am at home when my heart is in exile. My heart learned exile when I first left Egypt at age seven. By the time I was 33, when I moved to the United States I had lived in 4 different countries.

I had to wander in the ghorba that was the United States because the muscle that is my heart had to stretch and strengthen. I was driving toward myself

I moved to the U.S. in July 2000 with two suitcases and a husband waiting for me in Seattle. A year later, at the age of 34, I finally learned to drive and got my driver's license on the second attempt.

Two years after I arrived, I divorced the husband, packed my two suitcases into my car and spent 18 days driving across this new ghorba by myself. I did not want to start my new life in New York City after five hours on a plane. I had to wander; to become the Sawwah, the wanderer, of Halim’s song. I needed time to get to know America. Alone.

The day before I left for the drive, my brother was delegated by my family to convey their collective concern. "Mona. We know you're strong. We know this is a hard time. But you don't have anything to prove to us," he told me.

I understood that for someone who had been driving for just a year, an 18-day solo road trip across the U.S. was ambitious. And I also understood it was absolutely necessary. I had to wander in the ghorba that was the United States because the muscle that is my heart had to stretch and strengthen.

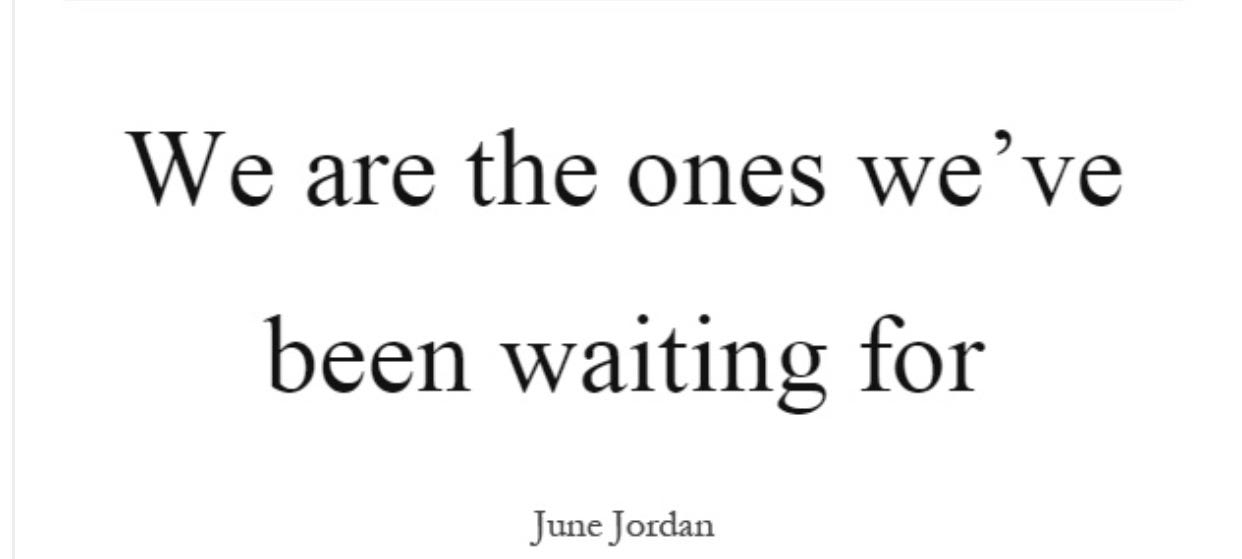

I was driving toward myself. June Jordan ended her Poem for South African Women in 1981 with words that I now have tattooed on my right arm next to a tattoo of the ancient Egyptian goddess Sekhmet: We are the ones we have been waiting for.

I was driving toward myself. I missed my family and friends, missed who I had been in Egypt and I needed an 18-day solo road trip to figure out, care for, and nurture who I was becoming in the U.S.

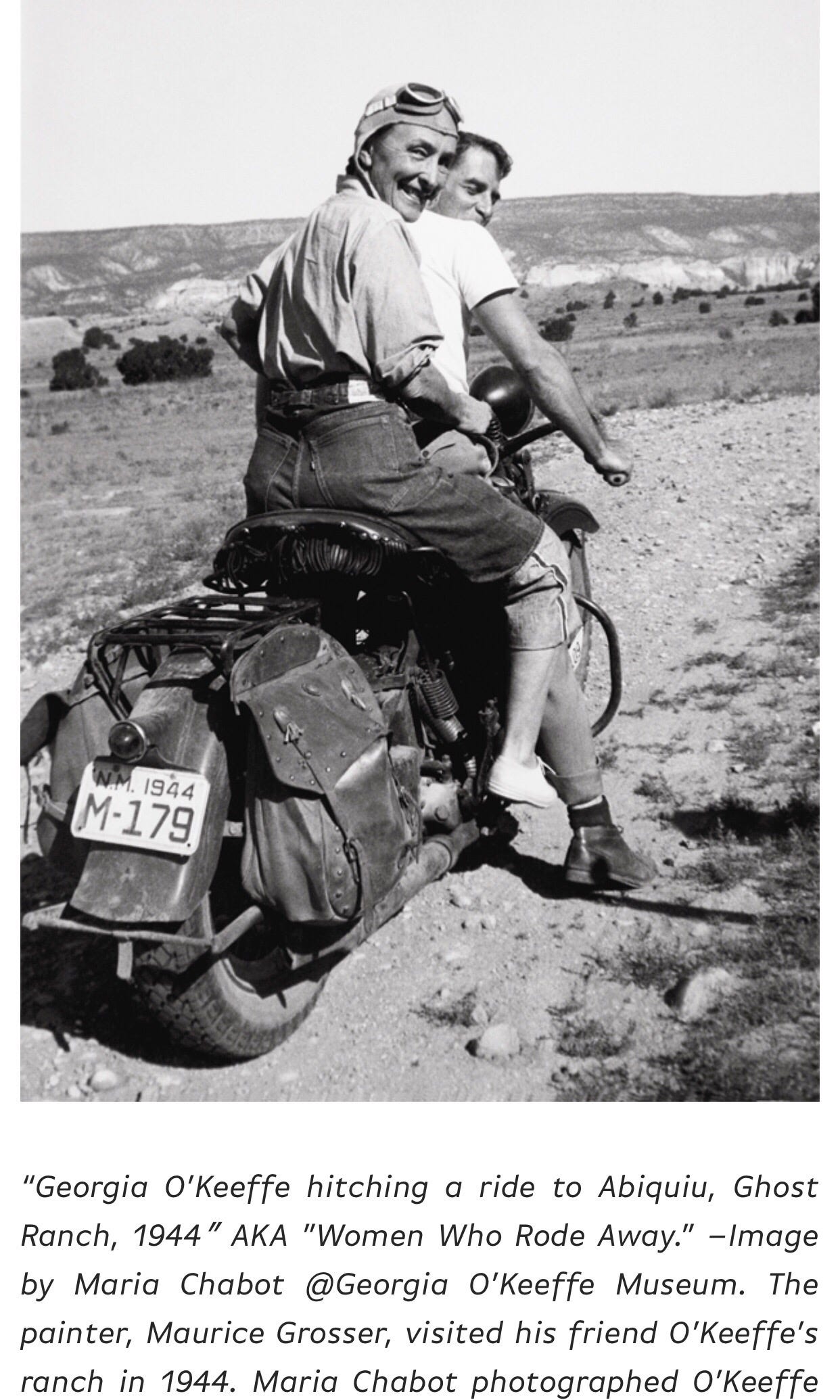

In Santa Fe, a stop I chose for Georgia O’Keeffe, at her eponymous museum, I saw a photograph by Maria Chabot of the artist hitching a ride to Abiquiu, Ghost Ranch, in 1944. It had been the image used for an exhibit of women artists which had featured O'Keeffe that was called ”Women Who Rode Away.” And there I found the theme of my solo road trip, most of my life, and a future memoir. I was a Woman Who Wandered.

I had never planned to ever move to the U.S. I had vowed never to get married. And yet in 2000 I did the latter, quickly followed by the former. When I left him, I knew there was only one city in the U.S. that could possibly contain my restlessness.

And I knew I had to drive to get there. I was both Thelma and Louise but I wasn’t going to drive off a cliff. I wasn’t done wandering. I had places to roam and patriarchal fuckery to fight.

Only NYC could contain my exiled heart because only in NYC could this brown-skinned wanderer be both at home and in ghorba, could feel the muscle she calls her heart soften as it continued to stretch in longing for other homes.

Are you exercising your heart in lockdown? Are you drawing on your reservoir of feminist nostalgia to keep that muscle you call your heart supple and ready to roam?

I spent three quarters of 2019 somewhere else - wandering, in the ghorba. Last year was mostly spent roaming: on tour in Spain promoting my first book, at a residency in Italy editing my second book and finessing the outline of the third one, turning Australia upside down by asking on live television how many rapists must we kill, promoting my second book at literary festivals in Nigeria and Canada, and getting goosebumps while keynoting in Soweto Theatre for the Abantu Book Festival.

I have spent three quarters of 2020 in lockdown, nudging and encouraging my heart to wander. Halim’s voice, as it did during those weekends in London, makes me long for what I’ve left behind and to miss already what is yet to come, and to be a Sawwah again.

Mona Eltahawy is a feminist author, commentator and disruptor of patriarchy. Her first book Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution (2015) targeted patriarchy in the Middle East and North Africa and her second The Seven Necessary Sins For Women and Girls (2019) took her disruption worldwide. Her commentary has appeared in media around the world and she makes video essays and writes a newsletter as FEMINIST GIANT.

FEMINIST GIANT Newsletter will always be free because I want it to be accessible to all. If you choose a paid subscriptions - thank you! I appreciate your support - you are helping me keep the newsletter free and accessible to all. If you like this piece and you want to further support my writing, you can like/comment below, forward this article to others, get a paid subscription if you don’t already have one or send a gift subscription to someone else today.

Sometimes I read one of Mona's essays before I begin a writing assignment, so I am freshly steeped in boldness, courage, owning my voice, remembering that my experiences flavor what I will write, no matter how "neutral" or "institutional" my words may appear.