Essay: How to be Dangerous

sudowoodo

Being dangerous is like daring yourself to shed skin. It’s as if the skin you once wore becomes too tight. You outgrow it because bravery is bursting your seams. You must go up a size or two because danger cannot be contained. And so there you are: shedding that skin!

Being dangerous is often synonymous with bombs, assassination, physical violence, threats to life–potentially useful tactics when the body politic is sick with fascism and authoritarianism.

And sometimes the politics of the body, specifically nudity–is the danger: to shed your skin by literally shedding your clothes.

Sitting naked in a room with seven strangers one night in Cairo in 2013 was one of the most dangerous things I’d ever done. None of us were clothed, let alone armed. Some of us passed around a joint, but no explosives or ammunition exchanged hands. But to the Egyptian body politic, our bodies were as dangerous as improvised explosive devices. Boom! The disruption and chaos of our “debauchery” were enough to blow up national security, family values, etc.

In her foreword to the foundational feminist anthology This Bridge Called My Back, Toni Cade Bambara set us the challenge: “The will to be dangerous…The work: to make revolution irresistible.”

I am not a nudist but for political reasons, I will try most things. And I understood that to be naked alongside seven strangers,, even inside a living room and not on the street, that night in Cairo was as powerful as that IED. I wanted bravery to burst me open. I wanted to short circuit my own protection mechanism. I wanted to blow the fuse that keeps my circuit from overloading.

As a writer, my body and my words are the cocktail in my molotov; the gasoline and the wick, ignited by danger, to firebomb the barricades that aim to contain me.

And I look to “uncontrollable” women, who teach me how to aim.

Being dangerous is like daring yourself to shed skin. It’s as if the skin you once wore becomes too tight. You outgrow it because bravery is bursting your seams.

I am proud when people tell me that something I wrote changed their lives. What an hounour to have had such an impact on someone’s ideas like that. What can I write now that would have such an impact on people, when fascism and authoritarianism have rendered the body politic sclerotic?

To be dangerous is to shake something foundational in a person.

When I first wrote about having sex before I got married, I thought “That’s the bravest I’ll ever be.” (In a column back in 2010 and in Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution)

When I first wrote about being nonmonogamous, I thought “That’s the bravest I’ll ever be.” (In The Seven Necessary Sins for Women and Girls)

When I first wrote about my two abortions, I thought “That’s the bravest I can be.”

When I first wrote about being queer, I thought “That’s the bravest I’ll ever be.”

It’s like shedding skin.

The absurdity of that: as preposterous as the danger posed by eight naked strangers sitting together, smoking a joint, and looking at more than each other’s eyes. .

I know the consequence of being dangerous to a dangerous dictator.

As a writer, my body and my words are the cocktail in my molotov; the gasoline and the wick, ignited by danger, to firebomb the barricades that aim to contain me. And I look to “uncontrollable” women, who teach me how to aim.

And yet, it’s always been the personal essays that made me pause, even for just a few seconds. Can I be that brave? There I am thinking this is the bravest and most dangerous I’ve ever been–by writing about sex with women as well as men, by describing the thrill of being naked with seven strangers in a living room in Cairo.

And then it doesn't feel enough. I outgrow it, I need more risk and vulnerability. I stretch and what once felt brave, feels insufficient. Bravery bursts my seams. It cannot be contained.

How brave must I be? How brave do I want to be? Is it a choice?

In Nawal El Saadawi’s novel “Woman at Point Zero” (a slim and unrelenting read--because patriarchy is unrelenting), Firdaus, a sex worker who is about to be put to death for murdering her pimp, tells the story of a life brutalized by a parade of misogynist and patriarchal oppressions.

“They said, ‘You are a savage and dangerous woman,’” Firdaus says. “I am speaking the truth. And the truth is savage and dangerous."

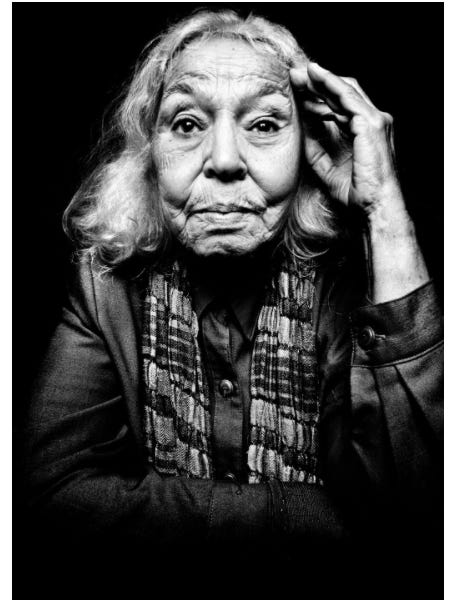

Dr Nawal El Saadawi soon after the January 25 Revolution © 2011 Platon for Human Rights Watch via The Guardian

Is being savage the same as being brave? When fascists and authoritarians make a mockery of truth, how much more savage and dangerous we must be!

What makes some people act and others observe? Why are some driven to act up while others remain passive? What drives one person to disobey and misbehave another to obey and behave?

We mostly all have a moral code so we usually know what’s strong and what’s right. So how come some see injustice and must consequently disobey, while others are quiet as long as it doesn’t hurt them personally?

Why do some disrupt injustice even when it hasn’t personally hurt them, while others remain silent, even when its ravages are obvious.

It can’t just be fear. We’re all socialised into fear.

So what is it?

I write to be dangerous, to survive, to be powerful, and ultimately to be feared.

“Writing is dangerous because we are afraid of what the writing reveals: the fears, the angers, the strengths of a woman under a triple or quadruple oppression. Yet in that very act lies our survival because a woman who writes has power. And a woman with power is feared. In the eyes of the world this makes us dangerous beasts,” Gloria Anzaldua wrote in her 1980 Speaking in Tongues: A Letter to Third World Women Writers.

If writing wasn’t dangerous, if books weren’t so potent, fascists wouldn’t burn them and authoritarians wouldn’t ban them. My first book, Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution, is banned in at least four countries.

Is being savage the same as being brave? When fascists and authoritarians make a mockery of truth, how much more savage and dangerous we must be!

I write to resist–against all forms of domination and socialization that insist women shut up.

Women who don’t shut up are where bravery, danger, and irresistible revolutions are made.

Pascale Lamche, filmmaker of a documentary on Winnie Madikizela-Mandela , explains why.

“...what is really astounding in South Africa is that on both sides of the apartheid divide – with the white Afrikaner nationalists and the black nationalists – they agreed on what a woman should be, which is to be a wife and stay at home and toe the line. And of course Winnie never toed the line: she was volatile and uncontrollable, and that was punished,” Lamche said.

Ugandan scholar, poet, and human rights activist Dr. Stella Nyanzi knows the danger of words and knows the consequence of being uncontrollable. Her glorious insistence on profanity in the face of authoritarianism offers a masterclass for those of us willing to defy, disobey, and disrupt.

Nyanzi is currently in Munich as part of a writer-in-exile programme run by PEN Germany. She lost her job because of her activism. Before she left Uganda, that country’s dictator had imprisoned her twice for essentially telling him to fuck off.

Pause for a minute and reflect: how does one woman and her Facebook posts and poetry threaten a man who has ruled a nation for over three decades? Nyanzi is a writer whose language is deliberate. She understands the agility of words and their ability to disturb the powerful and their networks of wealth and privilege.

“Women shall no longer wait for timid men

To fight for the liberation of Uganda.

We pack missiles in our pens and

grenades in our mouths

And shoot our truths at the dictatorship.”

—Women Shall No Longer Wait, No Roses From My Mouth, Poems From Prison By Stella Nyanzi.

“…my public nudity, in defense of democracy or fighting against an oppressor? Oh god, I love that body because it’s disruptive! … I’ve seen policemen coming to arrest me and I throw off my clothes and they run away. And that’s powerful,” Dr. Stella Nyanzi

Nyanzi’s insistence on violating patriarchy’s rules by talking explicitly about taboo subjects—be they the president’s buttocks, sex, sexuality, queerness—should be studied everywhere as a masterclass in the power of refusing to obey the rules of “politeness,” and a crash course on being brave and dangerous.

The body politic. The politics of the body. Nyanzi understands both acutely.

And her public nudity as protest teaches me why sitting naked with seven strangers in Cairo was the start of something dangerous.

“I go to nudity as perhaps the most convenient and most effective and cheapest route of protest for me. I think of my private nudity as private nudity. But my public nudity, in defense of democracy or fighting against an oppressor? Oh god, I love that body because it’s disruptive! And I have seen its effect. I’ve seen policemen coming to arrest me and I throw off my clothes and they run away. And that’s powerful,” she told the BBC.

Are you ready to be brave and dangerous? Can you be braver? Can you shed another skin?

Make revolution irresistible!

—You can support my work by upgrading to a paid subscription to help keep FEMINIST GIANT

—Via a one-time payment through PayPal or Buy Me a Coffee

—You can also support my work via Patreon

Mona Eltahawy is a feminist author, commentator and disruptor of patriarchy. Her latest book is an anthology on menopause she edited called Bloody Hell!: Adventures in Menopause from Around the World. Her first book Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution (2015) targeted patriarchy in the Middle East and North Africa and her second The Seven Necessary Sins For Women and Girls (2019) took her disruption worldwide. It is now available in Ireland and the UK. Her commentary has appeared in media around the world and she makes video essays and writes a newsletter as FEMINIST GIANT.

I appreciate your support. If you like this piece and you want to further support my writing, you can like/comment below, forward this article to others, or send a gift subscription to someone else today.