The most subversive thing a woman can do is to talk about her life as if it matters. Because it does. Her desire, especially when she is not supposed to desire or to be desired, is especially disruptive.

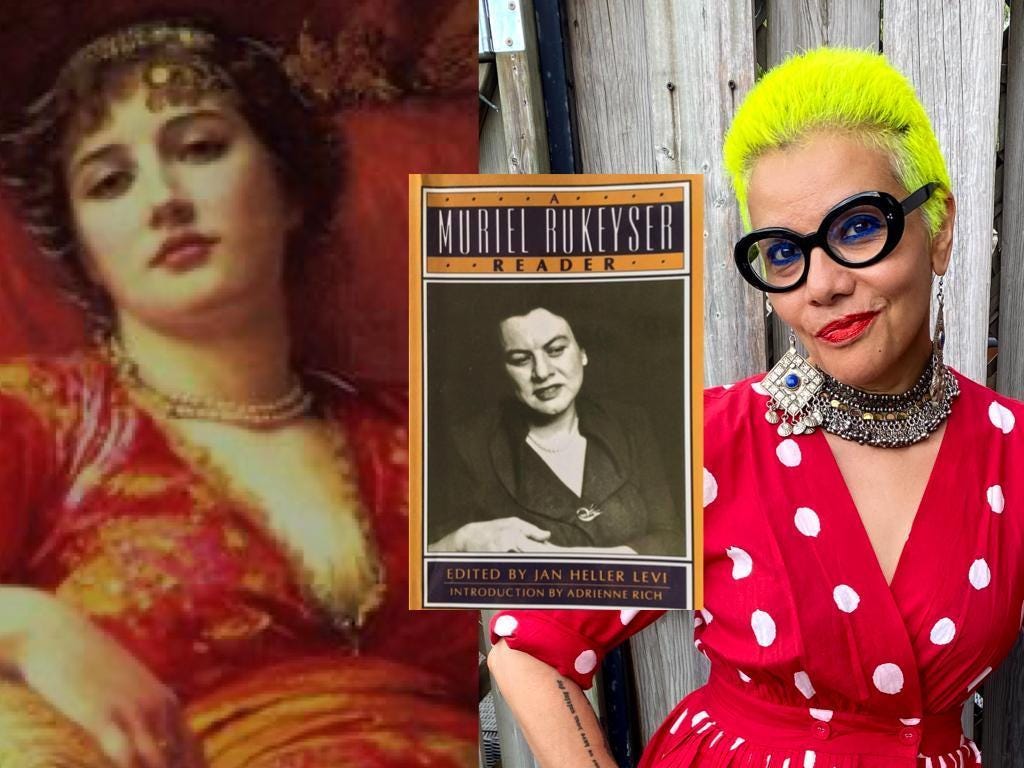

Among the poet Muriel Rukeyser’s assignments for her writing students was to begin a poem with the words “I could not say.” Acknowledging the taboo at the heart of a silence, can nudge expression free. Shaking desire free of taboos is revolutionary. The revolution is incomplete if it focuses on our autonomy only from the state. The state is not the only entity that exercises power over us, especially if we do not identify as cisgender men.

I am 54 years old today. On this and each successive birthday, I take stock of what I have not been able to say. It’s like those notches on the doorframe that mark your growing height as a child. My taking stock shows me how far I’ve come in nudging my expression free, in shaking my desire loose from the grip of taboo. So here goes.

I could not say, for too long, that I desired. Nor who I desired. Nor how I desired. I fought, myself mostly, to liberate my desire from guilt. Who among us is raised to desire freely? When desire is surrounded by silence and taboo, it is the most vulnerable who are hurt, especially girls and LGBTQ folks. And so whenever I speak publicly, I speak about desire and the revolutionary force of owning our desire; the liberation that beats at the heart of saying “I desire.” And when I speak, when I share, others share.

In New York, a Christian Egyptian-American woman told me how hard it was for her to come out as gay to her family. In Washington, a young Egyptian woman told the audience that her family didn’t know she was a lesbian. In Jaipur, a young Indian talked about the challenge of being gender nonconforming; and in Lahore, I met a young woman who shared what it was like to be queer in Pakistan.

The most subversive thing a woman can do is to talk about her life as if it matters. Because it does. Her desire, especially when she is not supposed to desire or to be desired, is especially disruptive.

Many of the women who share with me, I realize, enjoy some privilege, be it education or an independent income. It is striking that such privilege does not always translate into sexual freedom, nor protect women if they transgress cultural norms that surround desire. But desire is not the property only of those with money or a college degree. Sometimes, I hear the argument that women in the Middle East--a region that is increasingly known as South West Asia, to counter colonial geographical constructs-- have enough to worry about simply struggling with literacy and employment. To which my response is: So, because someone is poor or can’t read, she shouldn’t have consent and agency, the right to desire, to enjoy sex and her own body?

In many non-Western countries, speaking about such things as desire is scorned as “white” or “Western” behavior. I’ve been accused of being “obsessed” with sex because I insist on talking openly about desire. Who we can desire, how we can express that desire, who has the right to desire, and our right to determine for ourselves whose desire we can and cannot accept or reject: all those go to the heart of controlling our own bodies, of controlling our own lives, our futures and our destinies; of determining who we are, and who we are not, and where our place is in the world; of who we listen to, and whose words we reject. In short, all those go to the heart of determining all those things about ourselves which is called 'freedom'. Being able to speak of our desire - without fear, without penalty, and on the way of being ourselves - is at the heart of being free. It is at the heart of defying, disobeying and disrupting patriarchy.

Those are neither “white” nor “Western” questions and concerns. They are there in my heritage, as a woman born in Egypt to a Muslim family, whose first language is Arabic.

To desire and to be desired is political. How we fuck and who we fuck is political. Always the goal: to be free.

Listen to I’timad Arrumaikiyya, an eleventh century Arab poet who desired openly and unabashedly:

I urge you to come faster than the wind to mount my breast and firmly dig

and plough my body, and don’t let go until you’ve flushed

me thrice.

And here is Hafsa bint al-Hajj Arrakuniyya, a twelfth century poet, free with her desire:

If I keep you in my eyes until the world blows up I’d still want you more

. . .

I know too well those marvellous lips.

By Allah, I’m not lying if I say I love sipping their finerthanwine

delicious dew . . .

When you break at noon you’ll need a drink and you’ll find my mouth

a bubbling spring and my hair a refugeshade.

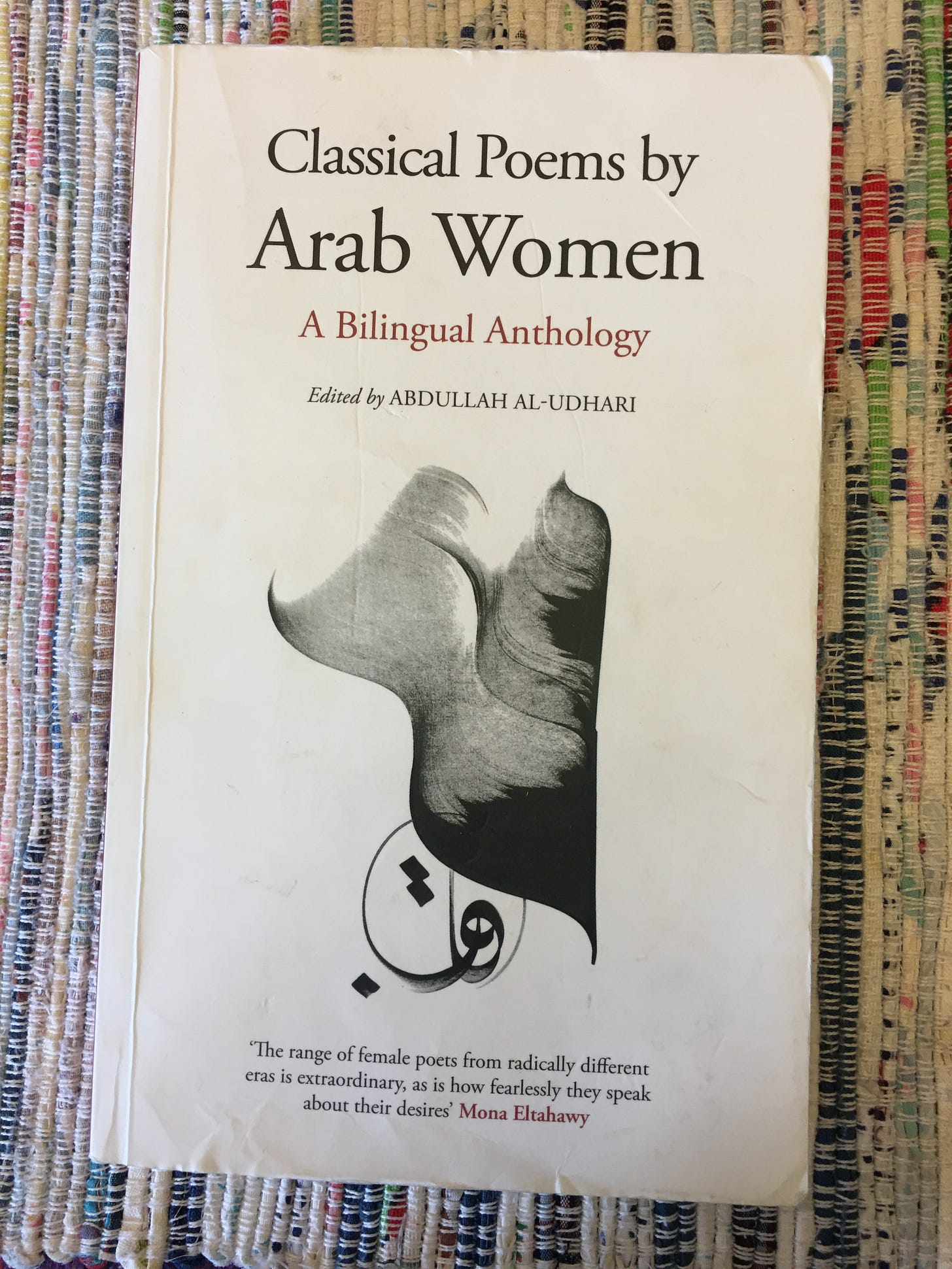

Those poets are part of the magnificent bilingual anthology Classical Poems by Arab Women, edited by Abdullah Al-Udhari. The collection ranges from 4000 BCE-622 CE--the pre-Islamic era known as Jahiliyya--through the Andalusian Period, from 711-1492. Imagine if these boldly and freely desiring female poets were taught in schools across the region? Imagine the power of seeing Arab and Muslim female poets so fearlessly speak about their desires!

Being able to speak of our desire - without fear, without penalty, and on the way of being ourselves - is at the heart of being free. It is at the heart of defying, disobeying and disrupting patriarchy.

“The standard history of classical Arab poetry begins and ends with a man, with the odd woman thrown in, who is either tearing her eyes out over the dead or tantalizing men’s desire with song and lute. Women poets appear as incidentals and the biographical dictionaries devote minimal space to them, in spite of the fact that their contribution to the growth of the literary tradition is as significant as that of the men,” Al-Udhari writes in his introduction to the anthology.

And if you need further proof of the disruptive power of female desire, Al-Udhari goes on to say that with the exception of one well-known poet, classical women’s diwans (collected poems) have not been published.

“A number of anthologies of women’s poems were edited in the Abbasid and later periods, but only two or three anthologies have been published, though in mutilated form. Contemporary editors, unlike the open minded classical anthologists, some of whom were respected theologians...assumed the role of society’s moral guardians and abused the integrity of the texts,” Al-Udhari wrote.

That contemporary editors are more conservative than their classical predecessors is a reminder that history is not a linear rush towards “progress” or liberalism. That is an especially poignant lesson in this time of a global pandemic that has been especially disastrous for women and girls around the world, especially Black, Indigenous and women of colour.

And for me, on this day when I turn 54, it is a reminder to reprise once again Muriel Rukeyser’s assignment to her students as a way to loosen the taboo around women and aging and desire. So here goes.

I could not say, for the longest time, that I desired men and women. I could not say, for the longest time, that being monogamous was suffocating me. What does desire look like liberated from the pressure of heteronormativity and enforced monogamy? What desire is a cis woman who is child free by choice “allowed” to have at 54 years of age? What does desire look like liberated from the pressure to have children? And perhaps hardest of all: during this past year, I could not say that I feared I had lost that ability to desire. I feared that I had lost a life force I had fought so hard for.

I did not know whether it was the stress and grief of a global pandemic or the unpredictability of perimenopause that seemed to have wrenched open a chasm that swallowed up my desire.

I did know how important desire was to me. And how important it was to be desired. And I know that I was not raised to be queer nor to be polyamorous. I arrived at both through a reckoning with myself that loosened the personal from the political; that wrestled free my lived reality from expectation. And I understood that the reckoning now was with taboos around age and the expectations that suffocated it. For too long, I had been told I “didn’t look” whatever age that I was. It was said to me as if it were a compliment. It was not. It was instead the loathing of aging that we are socialized into. How was I to stand in the power of my age when I was being “praised” for looking younger than I was. Not for all the money in the world would I go back to being younger. My 20s without exception and at least half of my 30s were miserable because I felt I had no power. And now here I am, with more power, being told I “didn’t look” this age I feel I’ve finally earned.

What does desire look like liberated from the pressure of heteronormativity and enforced monogamy? What desire is a cis woman who is child free by choice “allowed” to have at 54 years of age?

I have walked towards my desire by claiming my age.

Over the past year, I have written about my perimenopause. And here, I started to regularly post #ThisIs53, which will now become #ThisIs54. And in future essays, I will look closer at desire and getting older.

To desire and to be desired is political. How we fuck and who we fuck is political. Always the goal: to be free.

I could not say I stand in the power of my age, until I insisted I be seen in my age, as I was.

As Muriel Rukeyser wrote in her poem Käthe Kollwitz:

What would happen if one woman told the truth about

her life?

The world would split open

Let us split the world open.

Mona Eltahawy is a feminist author, commentator and disruptor of patriarchy. Her first book Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution (2015) targeted patriarchy in the Middle East and North Africa and her second The Seven Necessary Sins For Women and Girls (2019) took her disruption worldwide. It is now available in Ireland and the UK. Her commentary has appeared in media around the world and she makes video essays and writes a newsletter as FEMINIST GIANT.

FEMINIST GIANT Newsletter will always be free because I want it to be accessible to all. If you choose a paid subscriptions - thank you! I appreciate your support. If you like this piece and you want to further support my writing, you can like/comment below, forward this article to others, get a paid subscription if you don’t already have one or send a gift subscription to someone else today.