Essay: A Savage and Dangerous Woman: Nawal El Saadawi

The feminist author who challenged the taboos of sex, religion, and power

The first time I “met” Dr. Nawal El Saadawi she was speaking in a documentary about Egypt that my family and I were watching on our television set in London. I was born in Egypt but my parents moved us to London when I was seven years old. Like Nawal, they were medical doctors, and both of them had earned government scholarships to study for their PhDs in the UK.

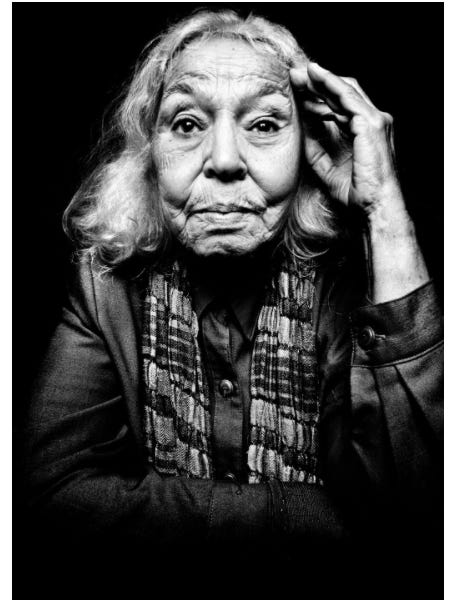

Dr. Nawal El Saadawi in 1986 Photo: Getty Images via BBC

There she was--an Egyptian woman with bright white hair who owned her power and spoke with absolute confidence in her words. Soon after, in the same film, an Egyptian man criticised her, complaining that she was ruining Egypt’s reputation. I can’t remember what she said but I do remember, more than 40 years later, that she terrified and thrilled 13-year-old me. Who was this woman who was so powerful that her words alone could ruin an entire nation’s reputation? I want that! I want to know her!

It was an early lesson in what feminism must be: terrifying and thrilling. Or “savage and dangerous” as Nawal wrote in her novel “Woman at Point Zero.” It is a slim and unrelenting read--because patriarchy is unrelenting--in which Firdaus, a sex worker who is about to be put to death for murdering her pimp, tells the story of a life brutalized by a parade of misogynist and patriarchal oppressions.

“They said, ‘You are a savage and dangerous woman,’” Firdaus says. “I am speaking the truth. And the truth is savage and dangerous."

In 1981, a year after we watched the documentary, Egypt’s then President Anwar Sadat imprisoned Nawal along with 1,500 activists. It was a lesson in the consequence of being a feminist whose words are so powerful they threaten not just an entire nation’s reputation, but its dictator too. Shortly after her imprisonment, Islamic militant soldiers assassinated Sadat during a military parade. She was released after three months in jail.

During my school years in the U.K., where we lived from 1975-1982, my teachers, mostly white women, would often ask me, “What does your father do?” when inquiring about the reasons my Egyptian family were first in London and then Glasgow. It was the height of second wave feminism and yet women who were working outside the home assumed my mother did not. My teachers assumed we were all just following my father around. My teachers could not imagine that an Egyptian Muslim woman could be in the U.K. for any other reason than to follow her husband there. They could not imagine that an Egyptian Muslim woman could be in the UK for any other reason than to be someone’s wife and someone’s mother, and not instead to study for her own PhD. Or that she could be all three things at once.

Which is why I am enraged that some refer to Nawal as the “Simone de Beauvoir of the Arab world.” Do not call her that. She is the Nawal El Saadawi of the world. We are not local versions of white feminists. If anything, my teachers with their anemic imaginations of my mother’s potential, needed Nawal El Saadawi’s feminism more than I needed theirs. Nawal’s feminism would have challenged their racist and parochial views and in doing so, she would have taught my teachers that feminism requires more than standing up to misogyny because women who were not white had more oppressions to fight against.

“They said, ‘You are a savage and dangerous woman.’ I am speaking the truth. And the truth is savage and dangerous."

The second time I “met” Dr. Nawal El Saadawi was on the bookshelves of my university library in Saudi Arabia. My family moved from the U.K. to Saudi Arabia when I was 15 years old and I was traumatized into feminism. There is no other way to describe it--because to be a female in Saudi Arabia is to be the walking embodiment of sin. As a woman in Saudi Arabia, as a girl there, you have two options: You either lose your mind or you become a feminist. I fell into a deep depression and then I became a feminist.

To this day, I have no idea what dissident professor or librarian placed feminist texts on the bookshelves at the university library in Jeddah, but I found them. They terrified and thrilled me. They saved my mind. I understood they were pulling at a thread that would unravel everything.

Before I found these books, I was depressed and suffocated by Saudi ultraconservatism but could not find the words to express my frustration at how religion and culture were being used as a double whammy against women. Those feminist texts gave me power to question and talk back to patriarchy. Those feminist texts were teaching me to become savage and dangerous.

I discovered feminist writings from all over the world, but even more significantly, I discovered that the part of the world I was from had its own feminist heritage, it was not imported from the “West,” as opponents of women’s rights sometimes claim and as those who call Nawal the “Simone de Beauvoir of the Arab world” imply.

Those feminist texts gave me power to question and talk back to patriarchy. Those feminist texts were teaching me to become savage and dangerous.

There was Huda Shaarawi, who launched Egypt’s women’s rights movement in the 1920s; Doria Shafik, who led 1,500 women as they stormed the Egyptian parliament in the 1950s and then staged a hunger strike for women’s enfranchisement; Fatima Mernissi, a Moroccan sociologist, whose books that questioned veiling helped me as I struggled with and then decided to stop wearing hijab; and there again was Nawal El Saadawi, a physician, author, and activist once more terrifying and thrilling me by promising to unravel all that was traumatizing me by insisting that I was not wrong to be horrified at patriarchy and its oppressions. These feminists from my faith and cultural background were foundational to my feminism because they understood what needed to be unravelled so that I could rebuild.

Soon after Nawal died, an Egyptian woman who is much younger than me wrote to tell me that she started reading Nawal when she was 15 years old. “Nawal was the first person to make me feel I was not insane and not unworthy,” she told me.

I had been deeply depressed when I was in my teens. She felt she was insane. Patriarchy fucks us over and it has us thinking we are the insane ones, that we are the wrong ones, that we are the unworthy ones; not the ways it enables and protects rape or the violence of cis men. And so to be told that you are not insane or unworthy, and to be given the power to tug at that thread that promises to unravel the ways patriarchal fuckery has socialized you into thinking you are insane and unworthy--that is the gift that Nawal El Saadawi gave us, that is the gift of feminism.

“Nawal was the first person to make me feel I was not insane and not unworthy.”

Nawal was the first woman to write about being subjected, at the age of six, to the crime of female genital mutilation (FGM). Egypt is the country with the highest number of women and girls—Muslims and Christian—who have been subjected to this horror that is carried out with the aim of controlling female sexuality. She made those connections in her first non-fiction book Women and Sex, which was banned for almost two decades. When it reappeared in 1972, she was fired from her job as director of public health for the government.

I am the from the first generation in my family to not be subjected to FGM. And one of the ways I honour Nawal’s work and fight back is to insist that I own my body, I deserve pleasure, and that I control my own sexuality.

It is not the job of feminism to burnish the reputation of patriarchy. It is not the job of feminism to mollify misogynists or placate patriarchy. It is the job of feminism to terrify misogynists and to destroy patriarchy.

The third time I met Dr. Nawal El Saadawi, she terrified and thrilled me in person when I interviewed her in Cairo, soon after I returned from Jeddah and started my career in journalism in the early 1990s. I do not remember what I interviewed her about nor what I wrote but I have not forgotten, more than 30 years later, this: “My grandmother told me religion was very simple: justice, freedom, and love,” she told me.

I did not understand the magnitude of what she was gifting me: a baton passed from an Egyptian woman who was born in the 1800s to Nawal who was born in 1931 who then passed it to me, who was born in 1967. I was struggling with my hijab, with what I had been taught about religion, with who I wanted to be versus who I was taught I should want to be. And there was justice, freedom, and love--tantalizing me with the promise of unraveling once again.

And how those three simple words challenged the patriarchal orthodoxy! That same patriarchy that insisted it owned our bodies as well as our minds. That patriarchy was both the regime—Sadat’s and then Mubarak’s following him—as well as the religious fundamentalists. The former, Nawal often insisted, were happy to give free reign to the latter as a weapon against liberal and secular dissidents.

Nawal’s insistence that religion be criticised along with all forms of authority was so threatening to Islamist militants that they put her on death lists. In 1993, a year or so after I first interviewed her, Nawal went into self-imposed exile in the United States for three years. It was a lesson in the consequence of being a feminist who challenged political as well as religious dictators.

When she fought what she called religious fanaticism and called out faith-based misogyny, Nawal always insisted that she targeted all faiths. Similarly, when she lived in the U.S., she did not spare the authorities there from her critiques of capitalism and class oppression that she targeted at the regime in Egypt. Her writing called out racial and gender inequality and she often critiqued the U.S. as an imperial power which was not as stringent in its separation of church and state as it liked to think it was.

The fourth time I met Dr. Nawal El Saadawi was in New York City where she came to give lectures soon after Egypt’s January 25, 2011 revolution. Nawal was in her 80s by then and it was fitting that this feminist revolutionary had been there, in Tahrir Square. I wonder if she found an echo for her grandmother’s credo of “justice, freedom and love” in the chants of “Bread, freedom, social justice, human dignity” that filled so many streets and squares across Egypt.

Dr Nawal El Saadawi soon after the January 25 Revolution © 2011 Platon for Human Rights Watch via The Guardian

And now, 10 years later I remember her answer to an audience question about why she was imprisoned: “I went to jail so that I could become free.”

Predictably, Nawal’s critics claimed that her scathing and unsparing critiques of patriarchy in the Arab world reinforced stereotypes of the region, much like that Egyptian man who accused her of ruining Egypt’s reputation. It is not feminists who reinforce stereotypes, nor do they ruin a country’s reputation. Rather it is misogynists and the patriarchal systems in place that enable those misogynists which reinforce stereotypes and ruin reputations.

It is not the job of feminism to burnish the reputation of patriarchy. It is not the job of feminism to mollify misogynists or placate patriarchy. It is the job of feminism to terrify misogynists and to destroy patriarchy.

Nawal El Saadawi spoke the truth and the truth is savage and dangerous. She terrified and thrilled generations of feminists into unravelling from the binds of patriarchy.

That is the essence of Nawal El Saadawi and the essence of feminism. That is the baton she has passed into our hands. She was savage and dangerous, and feminism has to be savage and dangerous.

Mona Eltahawy is a feminist author, commentator and disruptor of patriarchy. Her first book Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution (2015) targeted patriarchy in the Middle East and North Africa and her second The Seven Necessary Sins For Women and Girls (2019) took her disruption worldwide. Her commentary has appeared in media around the world and she makes video essays and writes a newsletter as FEMINIST GIANT.

FEMINIST GIANT Newsletter will always be free because I want it to be accessible to all. If you choose a paid subscriptions - thank you! I appreciate your support - you are helping me keep the newsletter free and accessible to all. If you like this piece and you want to further support my writing, you can like/comment below, forward this article to others, get a paid subscription if you don’t already have one or send a gift subscription to someone else today.