Essay: Of Human Interest

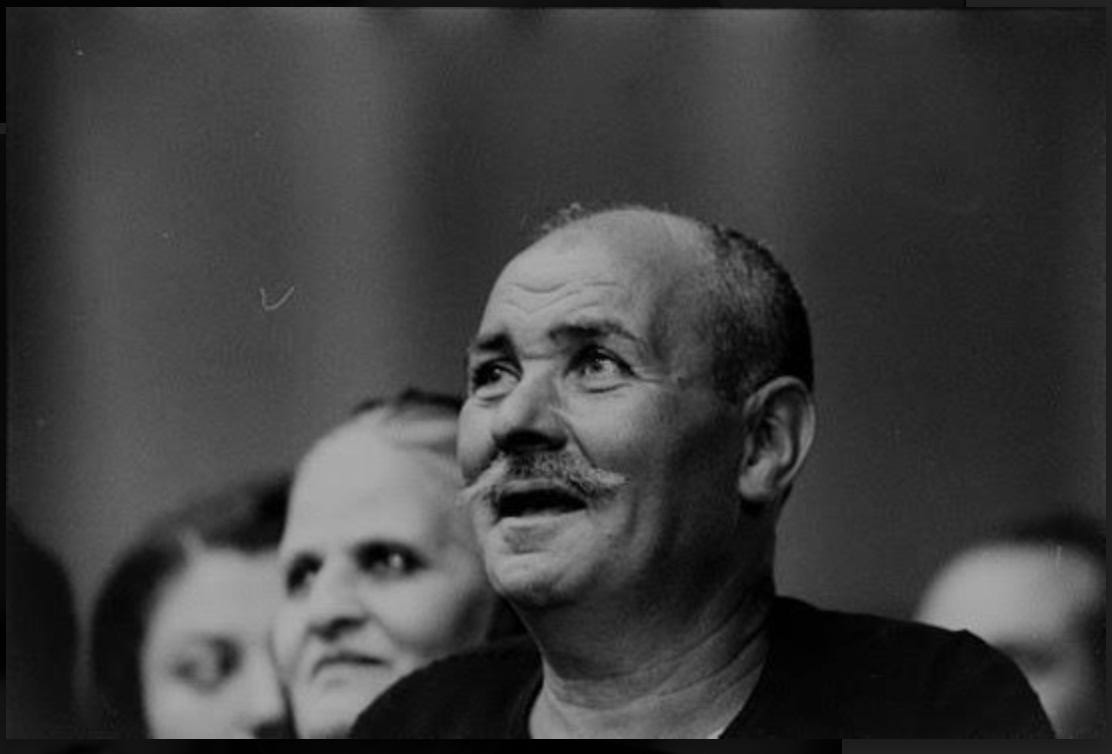

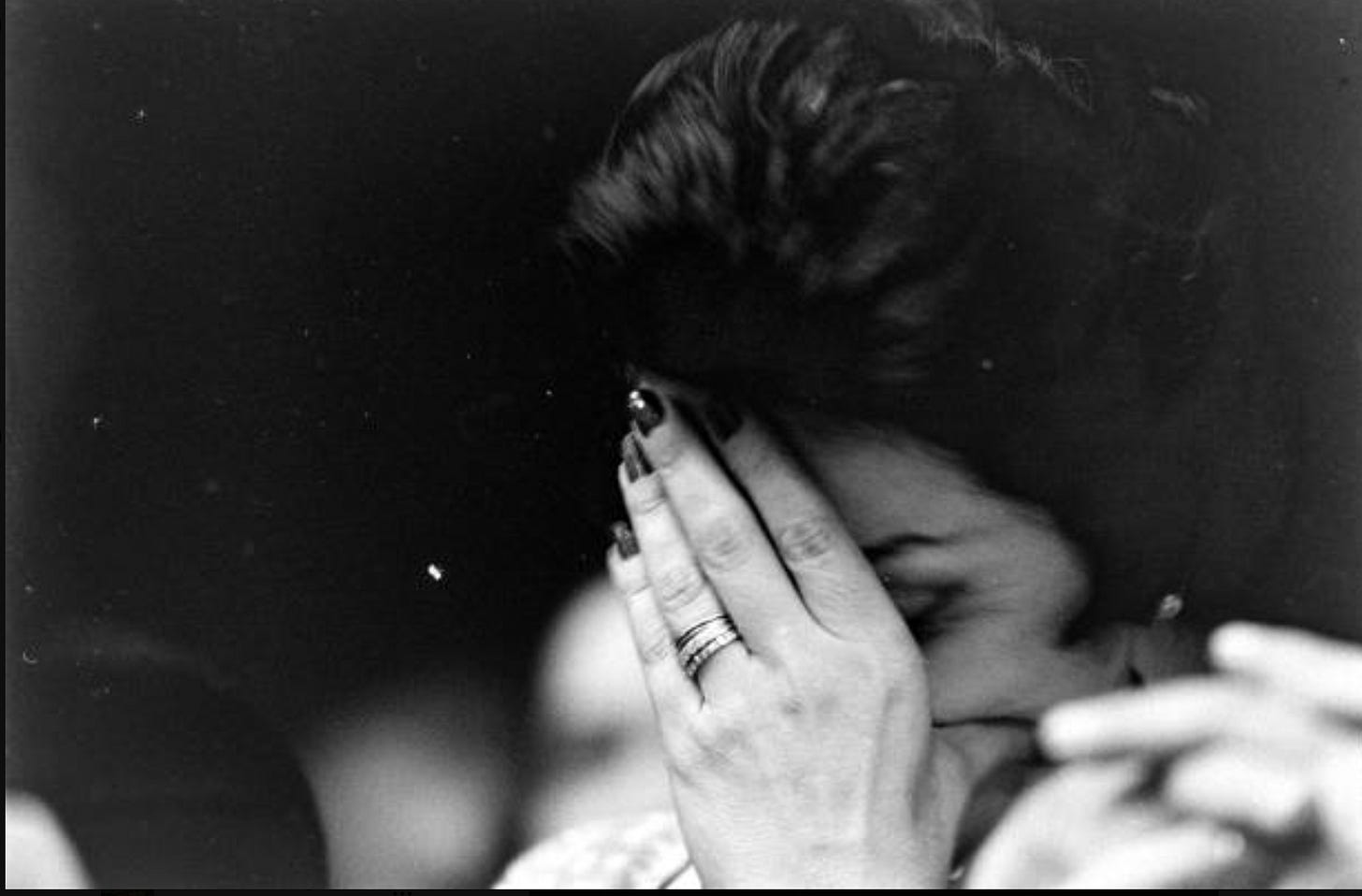

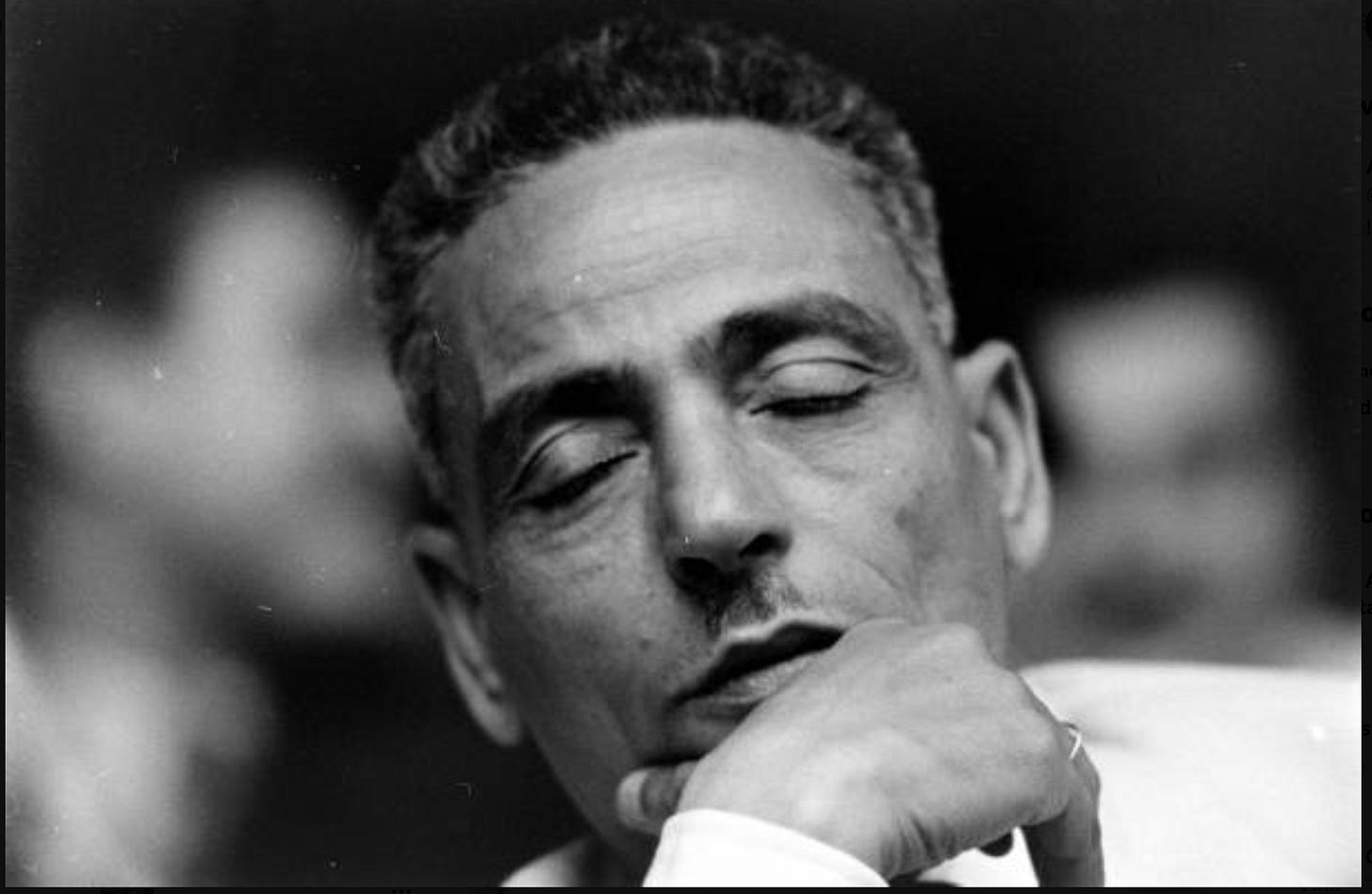

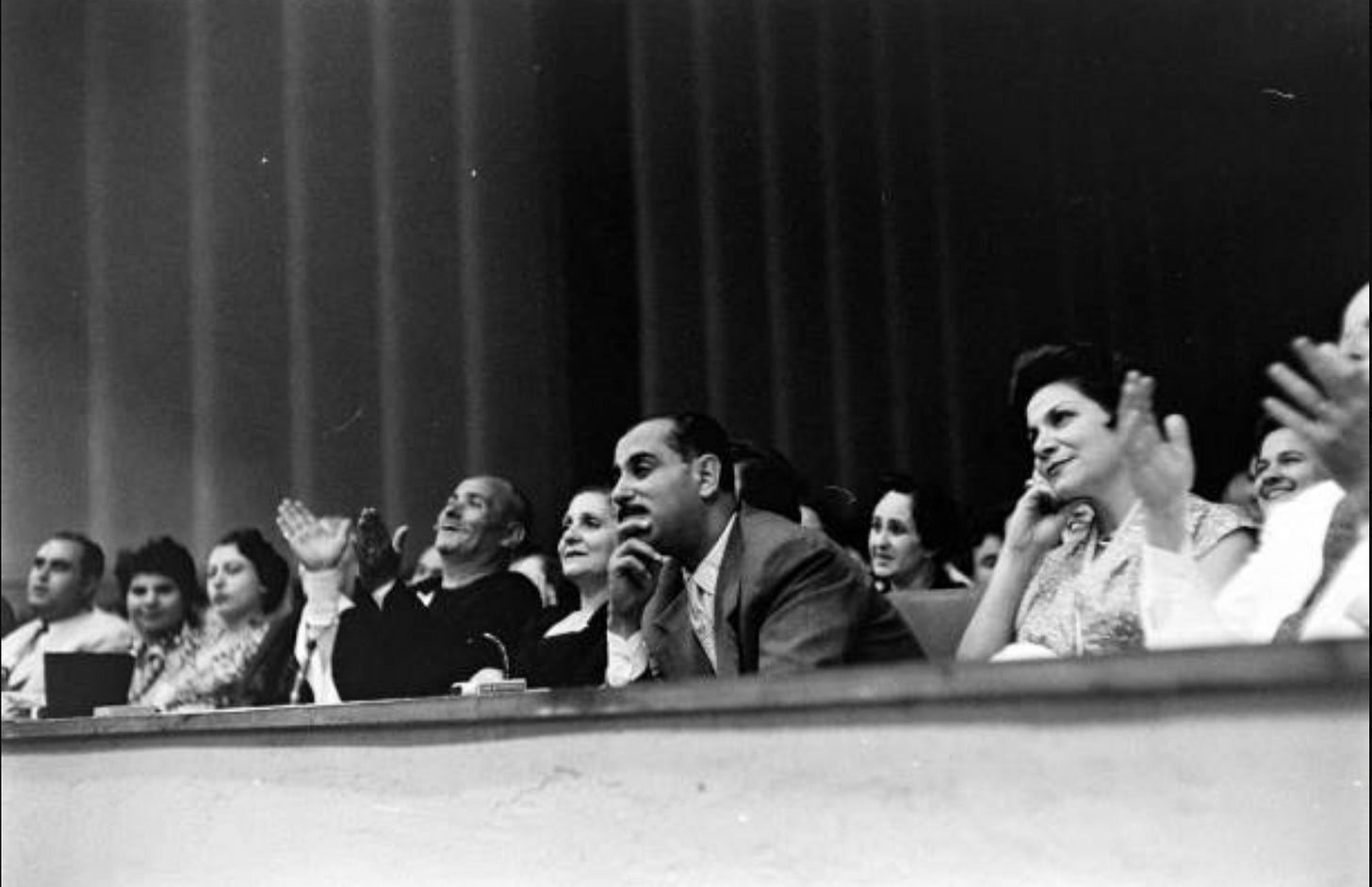

Unidentified audience member listening to Umm Kalthoum singing on Cairo's "Voice of Arabs" radio show. Cairo, 1956. Photo: Howard Sochurek

First published on Oct 14, 2024

During my first trip to Beirut, in 2009, I spent an evening at a theater on Hamra Street. Two women took the stage and read, in Arabic and English, from a book about to be released called Bareed Mista3jil (Express Mail).

It was a collection of oral narratives from lesbian, bisexual, queer, and questioning women, as well as trangender people, in Lebanon. The stories were from across the country–rural and urban, women of different faiths and sects. Some stories were about the difficulty or impossibility of coming out. Some were by people who had immigrated to Western countries only to find homophobia replaced by anti-Arab racism and Islamophobia.

One of the passages described the particular challenges that lesbians face in Lebanon..

“A lot more has been said about male homosexuality than female homosexuality. This comes as no surprise in a patriarchal society where women’s issues are often dismissed. And sexuality, because it touches on reclaiming our bodies and demanding the right to desire and pleasure, is the ultimate taboo of women’s issues. We have published this book in order to introduce Lebanese society to the real stories or real people whose voices have gone unheard for hundreds of years. They live among us, although invisible to us, in our families, in our schools, our workplaces, and our neighborhoods. Their sexualities have been mocked, dismissed, denied, oppressed, distorted, and forced into hiding.”

The worse that Israel’s atrocities become, the more I think about the exquisite, the beautiful, the ordinary, and the day-to-day from which lives are stitched–lives that are destroyed, lives that are discarded, lives blurred into a background, the easily diminished human toll of those atrocities.

Bareed Mista3jil was published by Meem, a support community for lesbian and bisexual women formed in Beirut in 2007. “Meem” is the phonetic pronunciation for the first letter in the Arabic word methleyya, a relatively recent addition to the Arabic lexicon that literally means “same,” as in “same sex,” and refers to lesbians. (For gay men, it would be methli).

I’ve been remembering that visit to Beirut. The worse that Israel’s atrocities become, the more I think about the exquisite, the beautiful, the ordinary, and the day-to-day from which lives are stitched–lives that are destroyed, lives that are discarded, lives blurred into a background, the easily diminished human toll of those atrocities.

We tell our own stories because we belong at the foreground, because when we propel ourselves from object to subject, the magnitude of our lives can never be diminished.

Unidentified audience member listening to Umm Kalthoum singing on Cairo's "Voice of Arabs" radio show. Cairo, 1956. Photo: Howard Sochurek.

I tell these stories not to “humanise.” If anyone needs to plead their humanity, it is Israel. This is where I turn the microphone to you; reverse the demands of random strangers on the internet from “Mona, do you condemn Hamas,” to “Hey, random stranger on the internet, do you condemn Israel?”

When you shift your focus from the background to the foreground, whose voices do you hear? When the U.S. invaded Iraq, for most Americans, Iraqis became the background in the destruction that George W. Bush wrought upon their country. The foreground was always American arguing for or against the destruction of Iraq.

What happens when object becomes subject?

Unidentified audience member listening to Umm Kalthoum singing on Cairo's "Voice of Arabs" radio show. Cairo, 1956. Photo: Howard Sochurek

Ten years before that event for Bareed Mista3jil in Beirut, during a reporting trip to Syria, I went to a funeral in Syria I never imagined I would attend. In the village of Ein al-Teini in south-west Syria, I watched Samia Sa'b sit on a hilltop and sob quietly as her brother's funeral was conducted 500 metres away.

Relatives used loudhailers to call out condolences across the landmined and fenced off gap that divides the village from the town of Majdal al-Shams in the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights. It became known as the "shouting valley".

When Israel seized the land in 1967, Ms Sa'b and her husband were on the Syrian side while her brother, Abu Ali S'ab and her family were in the Israeli-occupied sector.

"I hadn't seen him for more than 30 years," Ms Sa'b told me. "I didn't see my mother or father before they died either.

"Look at our heartache. We pray to God for the day when we can be reunited with our families. My daughter has three children I haven't even met them yet. Tell the world to end our misery."

Since the 1967 war, families have been going to the hilltop to shout their news and, on the Syrian side of the divide, to point out their family homes to anyone willing to listen.

I’ve never forgotten Samia Sa’b because bearing witness to her grief was enough of an intrusion of her pain. I hesitated long and hard before I let the journalist in me approach her. I didn’t need to ask how she felt. But I do need to move her to a foreground that rarely includes her in the articles and news reports from the region.

Unidentified audience member listening to Umm Kalthoum singing on Cairo's "Voice of Arabs" radio show. Cairo, 1956. Photo: Howard Sochurek

The year before I met Samia on that hilltop in Syria, I was a Reuters correspondent based in Jerusalem from where I would regularly go to the West Bank and the Gaza Strip on reporting trips to cover Palestinian news and issues.

One of my favourite places in Ramallah, in the West Bank, was a coffee shop called Kan Bata Zaman, which in English translates to This Used to be Bata. The coffee shop was in the location of what used to be a Bata shoe shop.

It was 1998, the year of the World Cup that was hosted, and eventually won, by France. I was at Kan Bata Zaman on June 16, during a match between Brazil and Morocco. I asked a group of young men if I could join them and ask them who they were supporting for a feature I wanted to write.

“Morocco, of course,” one of them told me. “I support any Arab country.”

“No man, Brazil. It’s always Brazil,” his friend said. “Until Palestine has a team in the World Cup, it’s always Brazil for me.”

Brazil beat Morocco 3-0.

Unidentified audience member listening to Umm Kalthoum singing on Cairo's "Voice of Arabs" radio show. Cairo, 1956. Photo: Howard Sochurek

I remember these stories not to “humanize” people from a region I am from and love. I remember those stories in the way that Umm Kalthoum’s audience would lose themselves in her songs.

I have been looking up pictures and films from the concerts of that Egyptian legendary singer because they connect me to beauty, heartache, pain, longing, passion, and love–they connect me to life.

A few months into Israel’s genocide in Gaza, I was watching one such performance and noticed that Bisan Owda had liked a video of an Umm Kalthoum song on Instagram. Bisan is a Palestinian journalist and storyteller who is followed and loved by millions of us around the world for her social media videos that begin with “Hi, everyone. This is Bisan from Gaza and I’m still alive.”

It brought me some comfort that Bisan found some comfort in Gaza; that she had lost herself and the horrors around her, if just for a few moments, in Umm Kalthoum’s universe.

Unidentified audience members listening to Umm Kalthoum singing on Cairo's "Voice of Arabs" radio show. Cairo, 1956. Photo: Howard Sochurek

One of my favourite Umm Kalthoum songs is Amal Hayati, which means The Hope of my Life. A love song, like so many that she sang. And it contains possibly my favourite lyrics ever:

“When you’re with me, it is difficult for me to blink, even for a second. It’s too difficult because I don’t want to miss your beauty or your sweetness, even for just a bit. That’s how much I miss you. That’s how much I need you.”

I share those lines now not to “humanize” us by persuading you that we too can love, that we too are passionate, that we too have hearts that break and hearts that long.

It is not our humanity that I am worried about. It is yours.

Thank you for reading my essay. You can support my work by:

Hitting the heart button so that others can be intrigued and read

Upgrading to a paid subscription to support FEMINIST GIANT

Opting for a one-time payment via buying me a coffee

Sharing this post by email or on social media

Mona Eltahawy is a feminist author, commentator and disruptor of patriarchy. She is editing an anthology on menopause called Bloody Hell! And Other Stories: Adventures in Menopause from Across the Personal and Political Spectrum. Her first book Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution (2015) targeted patriarchy in the Middle East and North Africa and her second The Seven Necessary Sins For Women and Girls (2019) took her disruption worldwide. It is now available in Ireland and the UK. Her commentary has appeared in media around the world and she makes video essays and writes a newsletter as FEMINIST GIANT.

FEMINIST GIANT Newsletter will always be free because I want it to be accessible to all. If you choose a paid subscriptions - thank you! I appreciate your support. If you like this piece and you want to further support my writing, you can like/comment below, forward this article to others, get a paid subscription if you don’t already have one or send a gift subscription to someone else today.