Essay: Perimenopausal Nefertiti and my Beautiful Belly

Standing in my power with the Egyptian Queen and the Master of Martial Arts

Photo: Herbert Knosowski, AP/Getty Images

This is an ode to my 53-year-old body.

I never wanted big breasts. Or rather, I never wanted breasts bigger than the size 34B ones I’ve lived with most of my life. And yet here I am with what I call my 34VV breasts.

That’s double V for double-vaccinated.

Soon after my second vaccine shot, it became uncomfortable to eschew bras--as I have in lockdown--and I sought the support of bralettes as an alternative to underwires and padded cups.

And then about two weeks after that second shot: my first period in 10 months.

I was at the tail end of Perimenopause. I had not had a period since October 2020 and I was counting down to 12 months period-free, in excited anticipation of getting to the other side of menopause.

Instead, there I was turning the bathroom closet upside down in search of pads, swallowing ibuprofen for cramps I never used to get with my periods and typing “Covid vaccine menstruation” into Google.

The short version: scientists are not sure. It could be a response of the immune system behaving as it should post-vaccine: did you know that the lining of the uterus--the shedding of which is a period--is part of the body’s immune system? Yeah, me neither.

It could be coincidental, have nothing to do with the vaccine, and instead be due to the impact of the hormonal shifts of Perimenopause.

Dr. Jen Gunther’s article looks at the possible answers. This BBC article and explainer are useful. Dr. Kate Clancy, an anthropologist, and her former colleague Dr. Katharine Lee have launched a survey documenting people's experiences with vaccination and menstruation.

My first vaccine shot--in April--was AstraZeneca. I got a Pfizer one for the second shot in June. I braced for the side effects of mixed dose vaccinations.

So delighted and grateful I am to have had my “Fauci ouchie” that I dressed in a much-loved gold sequin gown for it.

Being vaccinated is a privilege that is still unjustly out of reach for the majority of people around the world. We must push for vaccine equity and universal vaccination. Anti-vaxxers: you can fuck right off, if you’re here.

This is not an essay about the impact of vaccines.

This is an ode to my 53-year-old body: breasts, belly, period and all.

Earlier this year, I started posting photographs of myself on social media with the caption “#ThisIs53. It is not my birthday. I want you to see a 53 year old woman.”

I wanted to be seen. Not to be told, as I often have, that I don’t “look my age.” That is not the compliment some people think it is. But to say “Here is a middle aged woman. Look,” at a time when it seems that every time I look away, my body has changed.

And now millennia after Nefertiti, I understand that my power comes from saying “I am a middle aged woman. Look at me, breasts and belly and all.”

To look honestly at our bodies as we age is to begin to understand what Bruce Lee meant when he said, “Empty your mind. Be formless, shapeless — like water. You put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle, it becomes the bottle. You put it in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Now water can flow or it can crash. Be water, my friend."

To be water is to acknowledge the folly of “control.” Who wants to “control” their body? At a time when we enthusiastically vow to become ungovernable in the face of fascism, to believe we can “control” our bodies is not just the height of folly, it is a form of fascism of the self, surely.

I wanted to be seen. Not to be told, as I often have, that I don’t “look my age.” That is not the compliment some people think it is. But to say “Here is a middle aged woman. Look,” at a time when it seems that every time I look away, my body has changed.

In 2014, during my first visit to Berlin, I stood in front of the bust of Nefertiti at the Neues Museum and agreed that indeed “The Beautiful One is Here.” That is, after all, what her name means.

And I vowed to her that one day she and the other stolen and plundered treasures of my people would go from here--be it Berlin, London, New York City, Paris, Turin, Rome, and wherever else--to home. Doubling my rage at the crime of theft and “ownership,” was the guard standing nearby to ensure no one took a picture of what is undoubtedly one of the most beautiful art pieces of antiquity--or any time period, really.

“The Beautiful One is Here,” indeed.

And she is Perimenopausal.

Egyptian Museum of Berlin, Neues Museum, Berlin

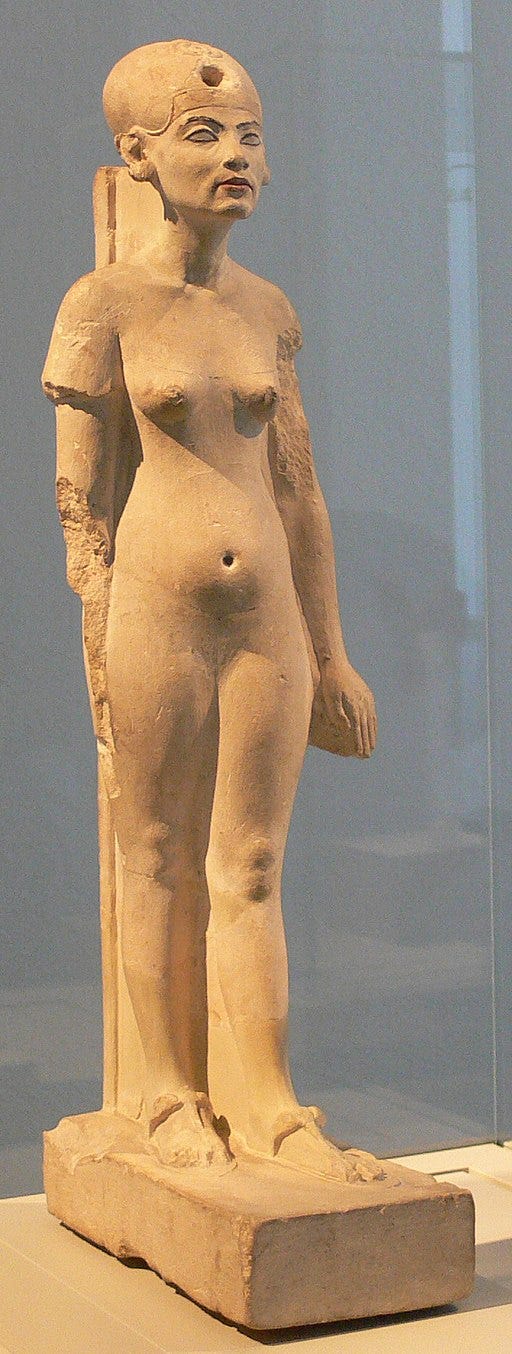

At least that is what I see now when I look at a 40 cm (16 inche) statuette known as Standing Nefertiti that I took a picture of in a hall full of treasures that can be photographed, not far from the famous bust, that magnet around which most museum visitors congregate.

I’d seen depictions of Nefertiti in Egypt, of course. But the bust? The museum refused to return it to Egypt, even for an exhibition in 2007, claiming it was too fragile to be moved. Imagine the audacity: asking for permission to display your ancestors’ heritage and being denied it by the descendants of those who robbed you of it.

When museums in the West continue to display what their colonizing ancestors stole from us, they magnify a historical theft with their contemporary insistence that they control our narrative.

There is a reason that, as problematic for the myriad reasons that he was, so many of us cheered when Killmonger in the film Black Panther tells the director of a museum that is clearly a stand-in for the British Museum in London, that he would be taking an artifact of African art from a display case. When the director tells him that the work is not for sale, Killmonger speaks for so many of us:

“How do you think your ancestors got these? Do you think they paid a fair price? Or did they take it… like they took everything else?”

Killmonger looking inside a display he is about to liberate. Or me looking at Nefertiti promising her she will go home one of these days.

When museums in the West continue to display what their colonizing ancestors stole from us, they magnify a historical theft with their contemporary insistence that they control our narrative. When I stand before Nefertiti and vow she will go home, I am standing in my right to my history and my present. It is that maturity that insists on writing an ode to my 53-year-old body.

At the time, I tweeted that picture of Standing Nefertiti and said “Curvy Nefertiti!” Perimenopause can last up to 10 years. I was most likely at the start of that transition and utterly oblivious to it when I met her. Now I feel I’ve caught up with her. My belly nods at her belly, knowingly; in the way that when you’re the only person of colour in a white space you nod knowingly when you see another person of colour. I see a middle aged, cisgender Egyptian woman, like me. And I nod, knowingly.

What is art if not also the echo of such nods, across millennia, telling us how familiar it is to be human.

When I stand before Nefertiti and vow she will go home, I am standing in my right to my history and my present. It is that maturity that insists on writing an ode to my 53-year-old body.

And for me, now aware of Perimenopause and the changes it has brought to my body, it is that nod across the millennia that makes Standing Nefertiti, more so than the famous bust, the Beautiful One. The former, representative of what is now known as the Tel Amarna period during which Akhenaten and his chief wife Nefertiti ruled from 1352 BC to 1336 BC, is like Bruce Lee’s water.

She is a middle aged woman who wants you to see her. “Look at me,” she said. “See my belly and my curves. Look.”

Akhenaten ushered in a new religion, capital, and--to the delight of my belly and me --style of artwork that depicted people, animals and objects more realistically.

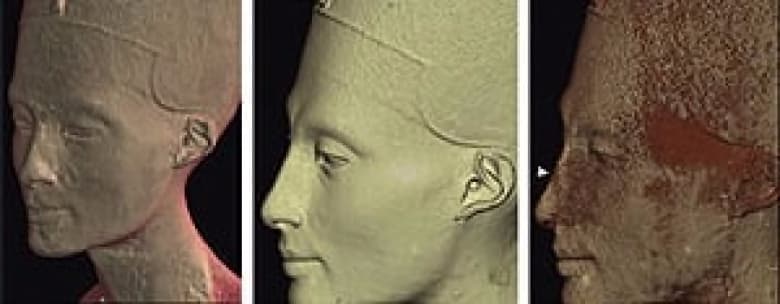

Researchers in Germany who studied the bust using CT scanning technology, discovered a detailed stone carving--a second face--that differs from the external stucco face. The inner or hidden face is more realistic: it shows Nefertiti with wrinkles, creases at the corners of her mouth, less-defined cheekbones and a bump on her nose. The royal sculptor Thutmose seems to have “smoothed” those out with the stucco external face. Who ordered those changes to the stone carvings of Nefertiti’s face?

A CT scan shows slight differences on the face underneath, including creases around the mouth and eyes and a bump on the nose of the stone version. ((Radiological Society of North America/Associated Press) ) via CBC

Was it the royal sculptor attempting to control his work of art? Was it Nefertiti’s husband, the pharaoh, trying to control how the world saw his chief wife? Was it Nefertiti herself, perhaps in an attempt to assert a control over her face that Perimenopause went on to teach her was folly?

Standing Nefertiti eschews that folly. She is a middle aged woman saying “Look at me, breasts and belly and all.”

Allow me some speculative history. Here’s how I imagine the conversation went with the royal sculptor. (Egyptologist friends: indulge me).

“Listen, Thutmose. Do you know what I will do to you if you try to “stucco smooth” my belly? I let you have my face but keep your hands off my belly, you misogynist, ageist shit. You hear me?”

Millennia before Bruce Lee, Standing Nefertiti understood that her power came from being like water--that her power was to stand in her body as it was, unconcealed by a stucco facade. And now millennia after Nefertiti, I understand that my power comes from saying “I am a middle aged woman. Look at me, breasts and belly and all.”

Mona Eltahawy is a feminist author, commentator and disruptor of patriarchy. Her first book Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution (2015) targeted patriarchy in the Middle East and North Africa and her second The Seven Necessary Sins For Women and Girls (2019) took her disruption worldwide. It is now available in Ireland and the UK. Her commentary has appeared in media around the world and she makes video essays and writes a newsletter as FEMINIST GIANT.

FEMINIST GIANT Newsletter will always be free because I want it to be accessible to all. If you choose a paid subscriptions - thank you! I appreciate your support. If you like this piece and you want to further support my writing, you can like/comment below, forward this article to others, get a paid subscription if you don’t already have one or send a gift subscription to someone else today.