Essay: Tender is the Fight

On Love

Image: Robert E. Rutledge

Read also: A Feminist in Her 50s in Love

And: Feminism, Football, Fucking

Love is not the opposite of hate. It is the opposite of indifference. We who demand a better world act out of love, not hate. We risk it all with the obsession of Majnun for Layla.

“At the risk of seeming ridiculous, let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love. It is impossible to think of a genuine revolutionary lacking this quality,” Che Guevara said.

Despite his critics, including anarchists such as myself, Che understood that we agitate not because we hate the world, but because we so desperately love it.

A revolution is a dare to the future as much as it is a reckoning with the past. It is a message in a bottle flung at our future selves that challenges us to remember. “Your imagination brought you to the streets. Your disobedience kept you there,” the message from the revolution insists.

And love is the verb, as Liz Fraser sings in Massive Attack’s Teardrop. “Love is a doing word,” that infuses our breath with a fearlessness that is temptation and salvation at once.

“As a culture worker who belongs to an oppressed people my job is to make revolution irresistible,” Toni Cade Bambera said.

We who cannot resist revolution, hand over our hearts as fuel, ready to have them smashed again and again, because as Maya Angelou said, “I don’t trust any revolution where love is not allowed.”

In 2012, still wandering in a daze over what riot police did to me just months earlier to punish me for my opposition to the regime, I met a man at a protest in Cairo, still wandering in a daze over a police-orchestrated massacre just months earlier to punish him and his comrades for their opposition to the regime.

“They broke my heart, Mona,” told me the man who had survived the massacre; as if a broken heart was the worst possible punishment for wanting a revolution.

I had just gifted myself my first tattoo–a gift that I’d promised myself when my bones healed. Not when my heart healed, because I knew that would take much longer.

And because love is the opposite of indifference, revolutionaries engaged in that grand struggle for life and liberty often describe the revolution in the way a lover talks of the beloved.

If hate is the accelerator that dehumanizes both its subject and object, to allow the former to kill the latter, then indifference is worse; it confirms that you are not worthy even of concern. If hate is a precursor to killing, then indifference is the spectator who watches.

Declaring yourself worthy of love, not from the enemy trying to kill you, but in spite of the enemy trying to kill you–is a way for the object of hate to liberate themselves, to say I love and therefore I live.

To revel in love, is to tap into a grand human activity of a revolution that erodes indifference. To point to our broken hearts is to say we cannot resist our love for this world.

And our love for this world drives revolution.

A revolution is a dare to the future as much as it is a reckoning with the past. It is a message in a bottle flung at our future selves that challenges us to remember. “Your imagination brought you to the streets. Your disobedience kept you there,” the message from the revolution insists.

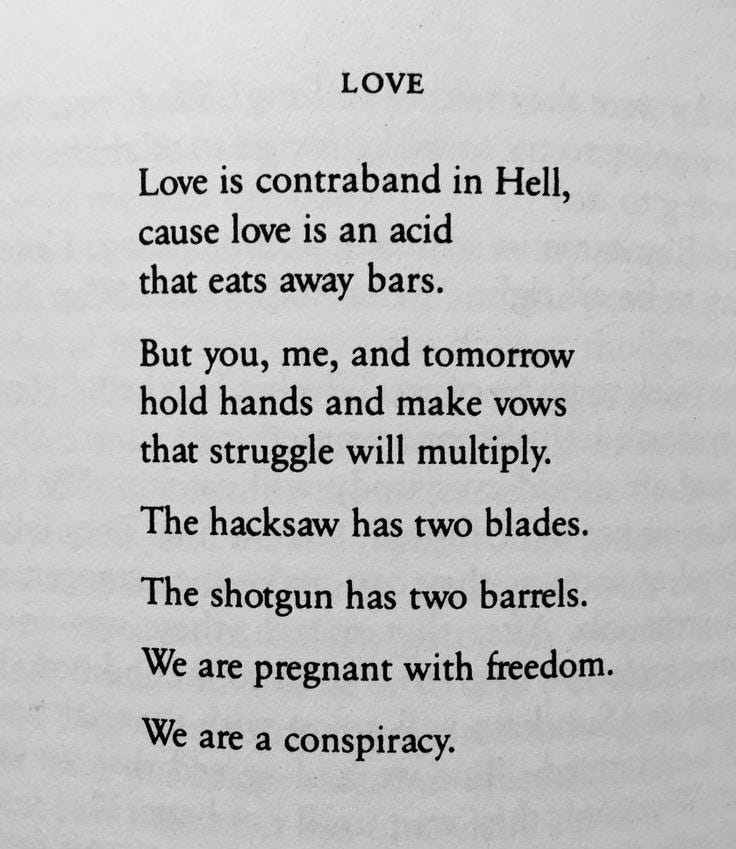

“Love is contraband in Hell,” writes Assata Shakur in the poem Love, in her autobiography. “‘cause love is an acid that eats away bars.”

It is not just the regime that can conspire, Assata tells us.

“But you, me, and tomorrow

hold hands and make vows

that struggle will multiply.

The hacksaw has two blades.

The shotgun has two barrels.

We are pregnant with freedom.

We are a conspiracy.”

It should come as no surprise that the broken-hearted man who survived the massacre and broken-hearted me became a conspiracy–a “gift of the revolution,” as Muriel Rukeyser wrote in her poem dedicated to Otto Boch, the Bavarian socialist and Olympic distance runner she met in Spain at the start of the civil war. Boch, an Internationalist volunteer who was killed with 600 others during the war, was the subject of at least three of Rukeyser’s poems.

Tender is the fight, I have learned from the revolution. And there is power in such tenderness.

When I was younger and had little power, I was all sharp edges and keep that love away from me. I was not ready to be lost in its power because I was not ready for the revolution. I wanted to be powerful and to be free, and in love, yes. But if I could not have the first two, well, then, love could wait. I chose me. I had to grow into the knowledge that a love that is free is powerful and tender; tender, not weak.

Tender is the fight, I have learned from the revolution. And there is power in such tenderness.

Feminist love insists on being both powerful and tender, because the sum total is freedom. Free love is revolutionary.

And perhaps the greatest poet of revolutionary love is June Jordan, who loved the world and her lovers, women and men, fiercely and with a tenderness that fuses the personal and political with the delicacy of an embroiderer stitching together a broken heart.

Even when conspiring against her enemies, love is a verb, a doing word.

“And if I

if I ever let love go

because the hatred and the whisperings

become a phantom dictate I o-

bey in lieu of impulse and realities

(the blossoming flamingos of my

wild mimosa trees)

then let love freeze me

out.

I must become

I must become a menace to my enemies.”

And perhaps the greatest poet of revolutionary love is June Jordan, who loved the world and her lovers, women and men, fiercely and with a tenderness that fuses the personal and political with the delicacy of an embroiderer stitching together a broken heart.

Whether her essays, that connect injustices at home and globally, or her poems, that inject desire and the power of the erotic into her meditations on a lover’s skin or the power of poetry to signal solidarity, June Jordan tells us again and again that love is not the opposite of hate, it is the opposite of indifference; that those of us who agitate for a better world, do so out of love, not hate. Join me, she says!

“These poems

they are things that I do

in the dark

reaching for you

whoever you are

and

are you ready?”

Feminist love insists on being both powerful and tender, because the sum total is freedom. Free love is revolutionary.

We, for whom revolution is irresistible, find each other through love and solidarity, Jordan says.

“I am a stranger

learning to worship the strangers

around me

whoever you are

whoever I may become.”

Let us conspire, this Valentine’s Day, to birth that freedom we are pregnant with.

Let us conspire! Will you be my comrade?!

Thank you for reading my essay. You can support my work by:

Hitting the heart button so that others can be intrigued and read

Upgrading to a paid subscription to support FEMINIST GIANT

Opting for a one-time payment via buying me a coffee

Sharing this post by email or on social media

Mona Eltahawy is a feminist author, commentator and disruptor of patriarchy. She is editing an anthology on menopause called Bloody Hell!: Adventures in Menopause from Across the World. Her first book Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution (2015) targeted patriarchy in the Middle East and North Africa and her second The Seven Necessary Sins For Women and Girls (2019) took her disruption worldwide. It is now available in Ireland and the UK. Her commentary has appeared in media around the world and she makes video essays and writes a newsletter as FEMINIST GIANT.

I appreciate your support. If you like this piece and you want to further support my writing, you can like/comment below, forward this article to others, or send a gift subscription to someone else today.

Dear Mona, this essay is astounding & brilliant. You move so deftly across & within revolutionary feminism. Yay you!