Essay: The Decade of Saying All That I Could Not Say

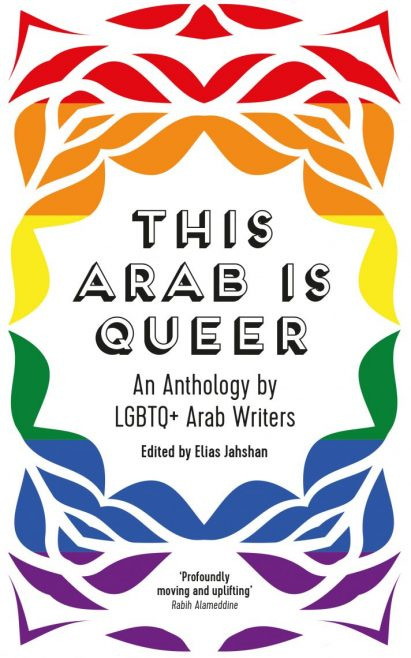

An excerpt from This Arab is Queer: An Anthology by LGBTQ+ Arab Writers Edited by Elias Jahshan

This Arab is Queer: An Anthology by LGBTQ+ Arab writers Edited by Elias Jahshan will be released by Saqi Books on June 16. Pre-order here.

It took Ireland and Bosnia to force a reckoning with my nesting dolls of secrets.

Of all the countries I have travelled to for work in the Western world, I have always felt most understood in Ireland. Unlike many other European countries which prefer to deny and distance themselves from talking about where I am from – Egypt and the surrounding region – and say, ‘it’s shit over there’, Ireland understood: ‘it’s shit over here too’. The stranglehold of the Catholic Church on everything from politics to education to geopolitics fostered understanding and empathy whenever I spoke there.

In 2015, Ireland became the first country to hold a referendum on marriage equality. The reckoning that such a referendum required inspired Ursula Halligan, one of Ireland’s most high-profile journalists, to come out at the age of fifty-four. (At the time of writing, I am also fifty-four). She wrote poignantly about a secret she thought she would take to her grave.

‘I was a good Catholic girl, growing up in 1970s Ireland where homosexuality was an evil perversion, she wrote. ‘It was never openly talked about, but I knew it was the worst thing on the face of the earth. So when I fell in love with a girl in my class in school, I was terrified.’ Halligan’s words gave me whiplash.

When I was sixteen years old, I was a good Muslim girl, growing up in Saudi Arabia where homosexuality was an evil perversion. I too fell in love with a girl in my class. But unlike Halligan – and this I now realise had been my denial and distance – I was in love with a girl and a boy at the same time and thought everyone else was too. I did not have a word for it, and I could not explore it beyond feeling jealous when the girl I was in love with told me she was in love with a boy and crestfallen when she did not say I, too, was an object of her love. It would take another three decades until I kissed a woman. But, tellingly, it would also take another decade until I kissed a man.

At around the age of seventeen, I began having nightmares that I had married the wrong man. Even when, at the age of twenty-one, I left gender-segregated Saudi Arabia for the more relaxed Egypt, my country of birth, I wanted very little to do with men. I was that good Muslim girl who was waiting for marriage and, much like Halligan, poured myself into work.

To say ‘had sex for the first time’ sounds like Christopher Columbus ‘discovering’ a country that existed long before he set sail.

When I read Halligan’s coming-out essay, I marvelled at the almost identical teenage love for a girl and I wondered how our journalism careers had helped us hide. I knew that I, at least, was hiding in plain sight.

Was I brave? Of course I was: I wrote articles that exposed the human rights violations of a regime that tapped my phone, had me followed, summoned me for interrogation at State Security several times, threatened to imprison me, and eventually made good on its threats that night on Mohamed Mahmoud Street in November 2011.

Was I brave? Of course I was not. I could not say, for the longest time, that I desired men and women. How could I when, for the longest time, men alone were off limits. How was I to figure out what I desired when desire for anyone was off limits?

When I was twenty-eight, I became – finally – sexually intimate with a person other than myself. That sounds like an awful lot of words to say, ‘lost my virginity’ or, ‘had sex for the first time’ but I lost nothing – it was fucking wonderful – as I had already been masturbating and enjoying the orgasms I gave myself. To say ‘had sex for the first time’ sounds like Christopher Columbus ‘discovering’ a country that existed long before he set sail. I have determined to retire those phrases I used to use once and for all.

I chose the person I was now having more orgasms with – a man I asked out and with whom I declared a truce in my war against femininity. When Y and I had penis-to-vagina sex – a phrase that did not exist in my lexicon in 1996 – I stopped reading the Qur’an. I could not stand reading the word ‘fornicators’ repeated again and again. And I started growing my hair. I am still trying to figure out why.

Short hair had, for years, been central to my identity. I am told that, when I was ten days old, my paternal grandmother had my ears pierced. This is a very common practice in Egypt, where gold stud earrings are a popular gift for baby girls. That same grandmother was a teacher and a smoker – in a society where smoking is considered a male privilege. When my mother complained to her that I cried every time she tried to detangle my hair after washing it, my grandmother’s advice was, ‘Just cut her hair short.’ So, from the age of three or so, my mother kept my hair very short.

When I moved to London in 1975, at seven, the first time I went downstairs to play with the other children, they asked me, in order: ‘What’s your name? Are you a boy or a girl?’ My English wasn’t so good and I ran back home.

None of the questions was asked with malice, but the last question was indicative of an expectation British society had for markers of ‘boy’ and ‘girl’. My neighbours didn’t see those markers in my appearance and they were confused.

But it was said with malice, when I was thirteen and in Cairo, by the guy who told his friend, ‘That girl used to be a boy and they gave her a sex change.’

What does a girl look like? Who taught me to be a girl?

In 2013 I finally kissed a woman. I had always assumed that, when I had a threesome, it would be between two men and me.

When I started growing out my hair after sex with Y, was I performing what I thought a sexually active, heterosexual woman looked like? Was I comfortable with the trappings of femininity now that I was older? When I had been younger, had I associated it with weakness? Were those years in hijab responsible for the power I had amassed?

When I removed my hijab aged twenty-five, I had worn it for nine years. On the day I stopped wearing it, I arranged for what I considered an intentionally ugly haircut. I did not want to be beautiful. I did not want my de-hijabing to be ascribed to a need for the male gaze’s approval. I wanted nothing to do with that gaze.

I was unsure if it was the gaze – that infamous eye of the beholder – or the beholder himself that I did not like.

Was sexual intimacy with Y giving birth to a new iteration of me? When did I start believing that nonsense about the ‘magic penis’, that heteropatriarchal nonsense that claims that being penetrated by a penis changes everything?

Adrienne Rich, a feminist and literary icon, defined compulsory heterosexuality as the ways by which a patriarchal and heteronormative world socialised women into heterosexuality – and I was taught a specifically Egyptian and Muslim version of it. I was raised to wait until I married a Muslim, Egyptian man to have sex. And for the longest time – too long – I obeyed. I could not find anyone I wanted to marry – or, more truthfully, I did not want to find anyone I wanted to marry. I became fed up with waiting and fed up with wondering, ‘What if it did not have to be a man?’

In 2013 I finally kissed a woman. I had always assumed that when I had a threesome, it would be between two men and me. But it turned out to be with a man whom I was seeing and a woman we invited to join us. It was also me who reached out and kissed her. And when the man left the room to use the bathroom, it was me who reached out for her once again. Still, I used no label and did not further explore my attraction to women.

In 2015, when I was getting to know the man who is now my Beloved and anchor partner, he told me in one of our earliest email exchanges that he was bisexual. I replied that I was polyamorous. I knew by then that monogamy was not for me, but I was still not ready to say that I, too, was bisexual. Learning how he explored and then acknowledged his sexuality has been a tremendous help, one that I credit with the progress I’ve made in shattering this final nesting doll of silence I’ve held onto for so long. While I was not ready to say I was bisexual, I did start to call myself queer – I considered my polyamory to be a form of rebellion and resistance to heteronormativity.

I was raised to wait until I married a Muslim, Egyptian man to have sex. And for the longest time – too long – I obeyed. I could not find anyone I wanted to marry – or, more truthfully, I did not want to find anyone I wanted to marry. I became fed up with waiting and fed up with wondering, ‘What if it did not have to be a man?’

The liberatory and revolutionary potential of queerness … became especially poignant for me when I first visited Sarajevo in 2016. I went to Vilina Vlas hotel and spa, which had been used as the largest rape concentration camp during the Bosnian War, and to Srebrenica, site of the worst massacre in modern European history. The previous night I had been to a queer club in the Bosnian capital with queer friends. It was a small club that played a mix of western pop and dance songs along with domestic folk-dance music. The club was packed, mostly with men, who frequently kissed. I held onto those images – the men kissing all around me as I danced with my friends – the next day, as I reeled at the atrocities that had been committed in the places I visited. The queerness I carried out of that radical space of openness and the transgressive sexualities that surrounded me were the perfect antidote to the horror of militarism that had been unleashed at Vilina Vlas and Srebrenica. Men should kiss each other more often and kill less – much less.

One of those men in the queer club in Bosnia kissed me.

‘I’m bisexual,’ he told me.

‘So am I,’ I replied.

I am very proud to be representing This Arab is Queer in the launch event at Bishopsgate Institute on Thursday 16 June! Join me, Elias Jahshan, Zeyn Joukhadar, Anbara Salam and host Paul Burston in-person or online.

Mona Eltahawy is a feminist author, commentator and disruptor of patriarchy. She is editing an anthology on menopause called Bloody Hell! And Other Stories: Adventures in Menopause from Across the Personal and Political Spectrum. Her first book Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution (2015) targeted patriarchy in the Middle East and North Africa and her second The Seven Necessary Sins For Women and Girls (2019) took her disruption worldwide. It is now available in Ireland and the UK. Her commentary has appeared in media around the world and she makes video essays and writes a newsletter as FEMINIST GIANT.

FEMINIST GIANT Newsletter will always be free because I want it to be accessible to all. If you choose a paid subscriptions - thank you! I appreciate your support. If you like this piece and you want to further support my writing, you can like/comment below, forward this article to others, get a paid subscription if you don’t already have one or send a gift subscription to someone else today.