Essay: Womb Kin

On Finding the Mercy in Our Humanity

A boy in Gaza breakdancing. Photography by Camps Breakerz Crew

CW: genocide, rape

It is the 30th anniversary of the genocide against the Tutsis in Rwanda. Over the span of 100 days in 1994, members of the Hutu ethnic majority murdered 800,000 people–one tenth of the population. Their targets were members of the Tutsi ethnic minority, Hutus believed to be Tutsis or who sheltered Tutsis, and members of the Twa ethnic minority.

In 2017, I went to Rwanda for genocide commemoration along with a France-based anti-racist group which took a group of activists and writers to pay respects at sites where French troops aided and abetted the slaughter they knew was happening - by doing nothing to stop it.

We read poetry and excerpts from memoirs of survivors of genocide from other parts of the world. I sobbed just about everywhere we went. How else to react at the Kigali Genocide memorial where the remains of 250,000 people are buried?

The Kigali Genocide Memorial. A photograph I took on April 7, 2017

I am not a crier and I am not known for communing with the dead, but the spirits of those hundreds of thousands of genocided people drum at your heart, demanding to know “Where were you? Where were you?” At one point, a genocide survivor who earlier that day had embraced a fellow survivor as they silently looked out onto the startlingly beautiful vistas of their country, comforted me. What a ridiculous notion: the genocide survivor comforting a visitor to his country who had come to pay respects to his slaughtered compatriots. Who should be comforting whom? But Thierry knew where he was–his heart had answered–he had endured and survived.

Eric and Thierry embrace. A photograph I took on April 6, 2017 at Bisesero memorial for the +40,000 killed in the area during the 1994 genocide against the Tutsis

I know now that I sobbed just about everywhere we went in Rwanda because those spirits drumming at my heart had composed a most clarifying assurance: that when I left Rwanda, it would be with less of my humanity than I had arrived with. Genocide diminishes us all.

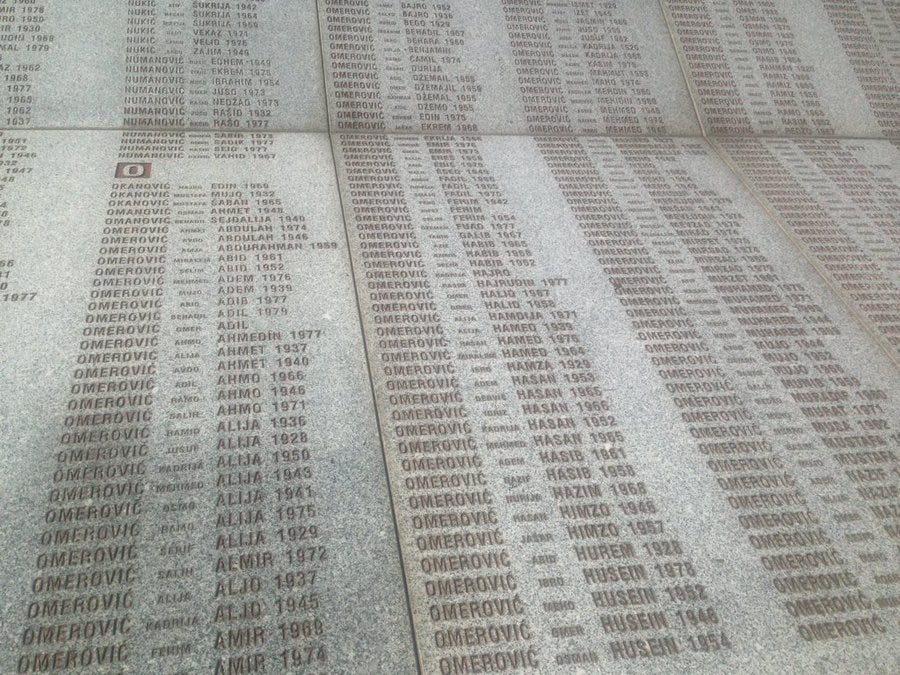

I knew this message well because the year before, I had been to a site of another genocide to pay respect, and there too I sobbed at the weight on my heart. In 2016, while I was visiting Bosnia, my feminist sister and comrade Nidzara Ahmetasovic took me to Srebrenica where, starting July 11, 1995 and for over a week, Bosnian Serb forces systematically murdered 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys and ethnically cleansed thirty thousand, in the worst crime of the 1992-1995 Bosnian war. It remains the only massacre on European soil since World War II to be ruled a genocide.

To prepare, I went to a genocide memorial at a museum in Sarajevo, and just the photographs–often of the most mundane events–of genocided people had me sobbing.

I know now that I sobbed just about everywhere we went in Rwanda because those spirits drumming at my heart had composed a most clarifying assurance: that when I left Rwanda, it would be with less of my humanity than I had arrived with. Genocide diminishes us all.

Before we went to Srebrenica, Nidzara took me to a spa hotel called Vilina Vlas, in the town of Višegrad. In April 1992, Serb paramilitaries turned the hotel into one of the biggest rape camps of the Bosnian war. There they held captive and raped 200 women and girls. By the time the camp closed in August 1992, only five had survived. It reopened just a few months later, as a hotel and spa again.

As the receptionist gave us a tour, I wanted to yell at the guest milling around in their robes, “Don’t you know women were raped in this hotel? How could you stay here as if nothing had happened?”

As I followed Nidzara and the receptionist through the corridors, I could feel the spirit of the women and the girls who had been kept prisoner in that concentration camp. I have a tattoo on my right forearm of Sekhmet, the ancient Egyptian goddess of retribution and sex. I touched her image with my left hand, like reaching for a talisman for strength, and kept muttering to myself, “We remember you, sisters. We honour you, sisters.” It was my promise to honour them by continuing to remind the world of what they endured, to avenge them as I am now by insisting that you hear what happened to them.

As soon as we exited the building, I asked Nidzara if I could hug her, and I sobbed as I did. I could not stop crying as we got in the car and drove away. Nidzara, who was sitting in the passenger seat by the driver, reached to the back seat to hold my hand. Again, Nidzara, who had lived through and survived the Bosnian war, including the siege that Serbs imposed on Sarajevo, was comforting me, the visitor paying respect at sites of atrocities in her country.

Genocide diminishes us all. Genocide dehumanizes us. All.

To bear witness to a genocide you have to scrape out your heart. Or is it your womb?

The Arabic word for womb--rahem--is the root word for mercy--rahma. I learned trauma in my mother’s womb, site of memories and mercy, root of life. Trauma, my twin, gestated alongside me in my mother’s womb, where I would kick at the sound of bombs that Israel dropped on Port Said, where my parents lived during the 1967 war, where I gestated. To this day, I have a phobia of thunder, which my mother believes triggers those womb memories.

Rahem, Rahma

How long is the shelf life of trauma induced by the 2,000-pound bombs that Israel has dropped on the children of Gaza, children who have already lived through three or four Israeli bombardments in their short lives already?

To bear witness/to bear a child/to reproduce the mercy that is the beating womb of our humanity.

I am childfree by choice. My womb has borne no children. But the seat of my mercy, its very core, is gutted by the horrors that Israel has committed in Gaza.

Muslims are taught the importance of maintaining family ties--to call, visit, check in on your family. The Arabic phrase used is actually Selet al-Rahem, which literally translates to Connections of the Womb.

I am paraphrasing it to Womb Kin because I want to examine mercy and what we owe our Palestinian kin--Womb Kin, connected by mercy and the humanity that ties us together.

Genocide devastates every level of kinship. It leaves a stench where once a family tree blossomed. In Srebrenica, at the cemetery that is home to the remains of the men and boys identified so far, you can see from the names how many families were gutted. Everytime I see a list of names of Palestinian families that Israel’s genocide in Gaza has wiped out, I remember those names in Srebrenica.

Names of men and boys genocided in Srebrenica. A photo I took on July 30, 2016

Is the Kinship of the Womb easier to trace when those being genocided lament in your mother tongue? The pain of diasporic Palestinians for their kin in Gaza is a devastation akin to shattering, I am sure. I am not Palestinian but Arabic is my mother tongue. Understanding the words with which Palestinians in Gaza wail and mourn has me, and so many other Arabic speakers, regardless of place of birth, tracing our kinship to the ways our tongues roll the r-sound in the word rahma with enough propulsion to send the rest of the word to the back of our throat for that deep double-h sound in the middle which does not exist in English. Mercy should be honoured and those majestic sounds in rahma deliver.

To bear witness to a genocide, is it your heart or your womb that you must scrape out, in order to go about your every day? In November, my gynecologist literally scraped out the lining of my womb, which had thickened with nowhere to go now that I am postmenopausal. Every step in the hospital tugged at the core of my mercy; a reminder of Israel's systematic destruction of everything that keeps Palestinians alive in Gaza, from doctors and hospitals, to journalists exposing its depravity.

Just days before I went to hospital, Palestinian children in Gaza held a news conference outside al-Shifa hospital, where they sought refuge. “We want to live. We want peace. We want food, medicine and education. Not bombs… we want to live as the other children live,” they said in English, to make sure they were understood. By us.

Were they heard?

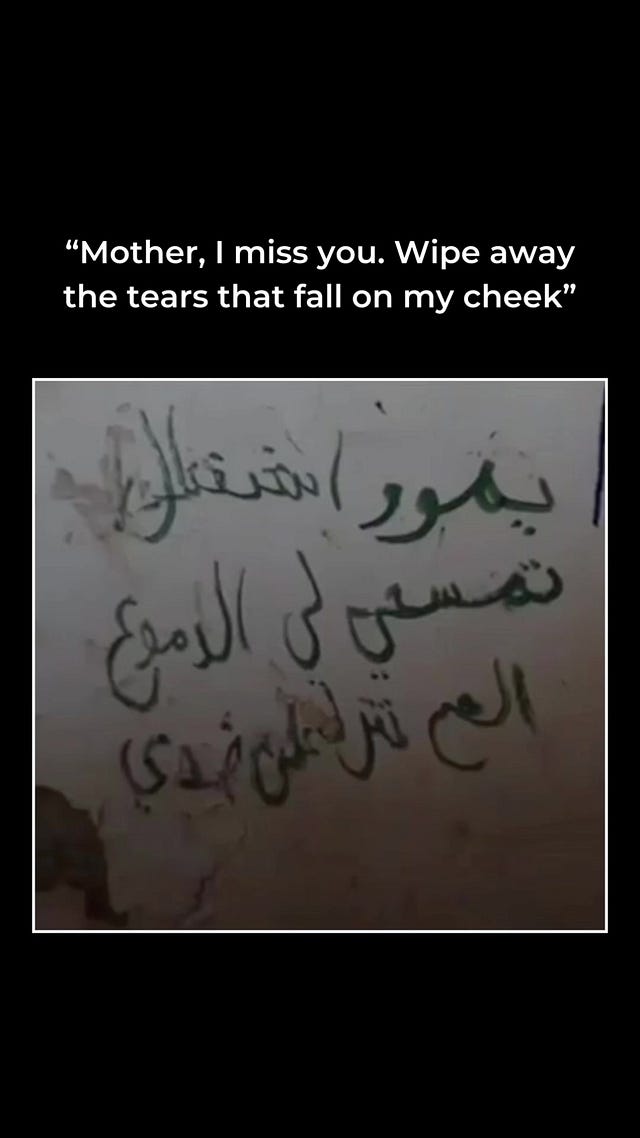

More recently, more words from al-Shifa hospital, this time written on its walls during Israel’s 14-day siege of the facility, which Gaza's civil defence said killed around 300 and which left Gaza’s largest hospital destroyed. The notes on the walls show the exhaustion and pain of the beseiged doctors, nurses and patients. Several of the words on the walls were yearnings by their authors for their mothers, in my mother tongue, in the way George Floyd called out to his mother as police were murdering him in broad daylight.

“Mother, I miss you, and I pray to see you soon. I swear to God that I love you.”

Israel has murdered more tan 13,800 children in Gaza.

“Mother, I am so exhausted but thank God for everything still. God willing, we will get out.

In January, UN Women estimated that two mothers were killed every hour in Israel’s genocide of Gaza.

“Mother, I miss you wiping off the tears running down my cheeks.”

Israel has murdered 33,000 Palestinians in six months in Gaza.

You do not need to trace your kinship to the womb to know that Israel’s genocide in Gaza diminishes us all. Arabic does not need to be your mother tongue for you to understand the savagery and barbarism that Israel is committing in Gaza. You do not need to be a mother to understand that genocide diminishes the humanity in us all.

While millions have marched and protested and barricaded and heckled their demands for Israel to stop, our elected officials refuse to stop Israel. Joe Biden, the president of the most powerful country in the world – he says –- can with one phone call end this genocide. Instead, in March, he sent 1,800 more 2,000-pound bombs to Israel to continue its destruction of Palestinian lives in Gaza. The majority of people in the U.S. oppose the genocide. Their leader refuses to listen.

Israel’s genocide in Gaza has made clear how unfree we are.

“Mother, I miss you, and I pray to see you soon. I swear to God that I love you.”

As we commemorate that genocide against the Tutsis in Rwanda, let us remember what we owed and failed to deliver to the people of that country. It is what our political leaders owe and have failed to deliver to the people of Gaza.

Just as too many (read: white people in the U.S. and their elected leaders) refused to see the fascism that Trump heralded, because for them fascism was something that happened in 1945, too many refuse to see genocide too, thinking it began and ended with the Holocaust. And the common factor in their kinship to victims of fascism and genocide is that they look or sound like them.

I am not Palestinian. Just as I am not Rwandan, Just as I am not Bosnian. I am human. And genocide diminishes us all. Genocide dehumanizes us. All.

What we owe our Palestinian kin is humanity; a recognition and rage at the injustice of their suffering and also a determination to see beyond just suffering. One of the most moving moments in Rwanda when I was there in 2017, was dancing with university students who had generously shared their testimony of the genocide. Many of them were children at the time and had lost several loved ones. I share the video of us dancing together every year when I commemorate the genocide.

Dancing with Rwanddan students

That determination for joy is what I see when Gazans share videos of dancing, amidst and despite the destruction that Israel rains upon them.

We owe it to our Palestinian kin to bear witness to their suffering as well as their joy. Palestinians do not owe us “proof” of their suffering to establish our kinship nor do they owe us a display of joy to establish their humanity. We owe it to ourselves to bear witness to how each successive genocide diminishes us. Gaza will haunt us all, demanding “Where were you?” decades from now. Understand this: ending the genocide in Gaza is for the sake of our collective humanity.

Thank you for reading my essay. You can support my work by:

Hitting the heart button so that others can be intrigued and read

Sharing this post by email or on social media

Upgrading to a paid subscription to help keep FEMINIST GIANT free

Opting for a one-time payment via buying me a coffee

Mona Eltahawy is a feminist author, commentator and disruptor of patriarchy. She is editing an anthology on menopause called Bloody Hell! And Other Stories: Adventures in Menopause from Across the Personal and Political Spectrum. Her first book Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution (2015) targeted patriarchy in the Middle East and North Africa and her second The Seven Necessary Sins For Women and Girls (2019) took her disruption worldwide. It is now available in Ireland and the UK. Her commentary has appeared in media around the world and she makes video essays and writes a newsletter as FEMINIST GIANT.

FEMINIST GIANT Newsletter will always be free because I want it to be accessible to all. If you choose a paid subscriptions - thank you! I appreciate your support. If you like this piece and you want to further support my writing, you can like/comment below, forward this article to others, get a paid subscription if you don’t already have one or send a gift subscription to someone else today.