Global Roundup: Antigua and Barbuda LGBTQ Activist, Mexico Mother Seeking Justice for Femicide, Tunisian Black Women, Queer African Artists, Parisian Feminist Collective

Curated by FG Contributor Samiha Hossain

JESSIE WARDARSKI / AP PHOTO

LGBTQ activist Orden David in Antigua and Barbuda took his government to court in 2022 to demand an end to the Caribbean country’s anti-sodomy law. A top Caribbean court ruled that the anti-sodomy provision of Antigua’s sexual offenses act was unconstitutional. LGBTQ-rights activists say David’s effort, with the help of local and regional advocacy groups, has set a precedent for a growing number of Caribbean islands. Since the ruling, St. Kitts & Nevis and Barbados have struck down similar laws that often seek long prison sentences.

I realized that with our community, we’ve gone through a lot and there’s no justice for us. We all have rights. And we all deserve the same treatment. -Orden David

The ruling said Antigua’s 1995 Sexual Offences Act “offends the right to liberty, protection of the law, freedom of expression, protection of personal privacy and protection from discrimination on the basis of sex.” The law stated that two consenting adults found guilty of having anal sex would face 15 years in prison. If found guilty of serious indecency, they faced five years in prison. Such laws used to be common in former European colonies across the Caribbean but have been challenged in recent years. Courts in Belize and Trinidad and Tobago have found such laws unconstitutional; other cases in the region are pending.

Growing up, David was bullied in school and discriminated against outside its walls. People took photographs of him and posted them on social media, called him slurs and attacked him physically.

What pushed me to go forward with this litigation case, to challenge the government, is that experience that I’ve gone through in life. -Orden David

Working for Antigua’s AIDS Secretariat, David tests people for sexually transmitted diseases, distributes condoms and counsels them on prevention, treatment and care. He’s also president of Meeting Emotional and Social Needs Holistically, a group that serves the LGBTQ community. And he is an active volunteer: on a recent night, he walked across dark alleys of downtown St. John’s to hand out condoms to sex workers.

Soledad Jarquín sits in her living room, next to an altar dedicated to her daughter, María del Sol Cruz Jarquín, who died by femicide five years ago. ENA AGUILAR PELÁEZ, GPJ MEXICO

Soledad Jarquín is an award winning journalist whose daughter María del Sol Cruz Jarquín, a photographer, was shot in Juchitán de Zaragoza, Oaxaca, on June 2, 2018. It took until October 2021 for her death to be classified as a femicide instead of a homicide. Still, Jarquín says she has heard nothing from authorities about her daughter’s case.

Every day that goes by, it’s like I see a wall in front of me that grows and grows while I try to climb it, never reaching the top. It’s the reflection of that feeling of impotence that comes from the mixture of impunity from my daughter’s femicide, combined with the intense pain of having lost her forever. It’s all so intense that it affects the day-to-day life of my entire family. -Soledad Jarquín

Despite an alarming rise in femicides, campaigners say too many cases are not deemed femicide from the start, which means losing the opportunity for important investigation procedures. Many homicides of women are classified as culpable homicide, which can imply an accident, letting the state off the hook for forming public policies to prevent gender-based violence.

Like many relatives of those who have died by femicide, Jarquín says, she has had to push authorities to investigate her daughter’s death. Last summer, driven by the lack of action, she took her case to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, in Geneva. It was the committee’s first femicide case from Oaxaca. On the fourth anniversary of her daughter’s death, she appeared before the Human Rights Council, an intergovernmental body within the United Nations. Jarquín says members were expecting a representative from Consorcio Oaxaca to speak, but instead, she took the floor.

I had to keep my voice from cracking and crying because my time [was limited to a minute and a half], and I had to make the most of it. I told myself, ‘Later you cry and do what you want, but here you hold on and say it.’ -Soledad Jarquín

Now all Jarquín can do is hope and wait for the international court to make recommendations to Mexico’s legal system on how to deal with the case. As a member of the U.N., Mexico is legally bound by resolutions passed by U.N. bodies.

Photo: Khawla Ksiksi

CW: anti-Black racism, racist language, misogynoir

Black Tunisian women say they are experiencing more instances of racism after the country's president criticised sub-Saharan migrants. In February, President Kais Saied ordered "urgent measures" against sub-Saharan migrants, accusing them of a "criminal plot" to change the country's demographics and cultural identity. He went on to say that immigration came from "a desire to make Tunisia just another African country and not a member of the Arab and Islamic world".

There has since been a rise in violence against Black African migrants, according to Human Rights Watch, and the statement has only made the situation worse for Black Tunisians, who make up between 10-15% of the Tunisian population, according to official figures.

Activist Khawla Ksiksi, a Black Tunisian citizen, says sometimes when she speaks in Arabic, people will answer in French because they don't want to acknowledge a sense of kinship with her. Ksiksi, who is a co-founder of the Voices of Black Tunisian Women collective, wants to challenge the misconception that Black Tunisians do not exist. A lack of Black representation in places of social and political power, she believes, reinforces the idea that there are no Black Tunisian citizens.

My skin colour says I don't belong so as Black Tunisians we have to constantly prove that we are enough…In school, I had to always have the best grades because all the teachers thought that I would cheat because in their minds Black people are not very intelligent. - Khawla Ksiksi

In response to the president's statements, some Black Tunisian women, including academic researcher and lecturer Houda Mzioudet, took part in the "Carrying My Papers Just In Case" trend on Facebook. They wore their passports and ID visibly on their clothes to show they were Tunisian but also in solidarity with migrants. Mzioudet says the problem is that Tunisian society has been built on a "homogenised nationhood" that does not allow the discussion of racism. The slave trade, which involved the selling of Black Africans, was abolished in Tunisia in 1846 but its legacy lives on.

There has been a continuation of domestic slavery, although they are no longer calling Black people slaves but instead servants - hence the Tunisian Arabic word to refer to a Black person is 'wessif' meaning 'servant'. -Houda Mzioudet

In 2018, Tunisia passed a landmark law to criminalise racial discrimination, in particular anti-Black racism against Black Tunisians and Black African migrants. It became the first country in the Arab region to make discrimination specifically on racial grounds a criminal offence. Both Ksiksi and Mzioudet say that despite these laws, the government has allowed the discrimination and inequality faced by Black Tunisians to flourish.

In February, hundreds of people took to the streets of Tunis in support of Black African migrants and Black Tunisians, a positive sign that there is hope that the younger generation wants to see change, says Mzioudet.

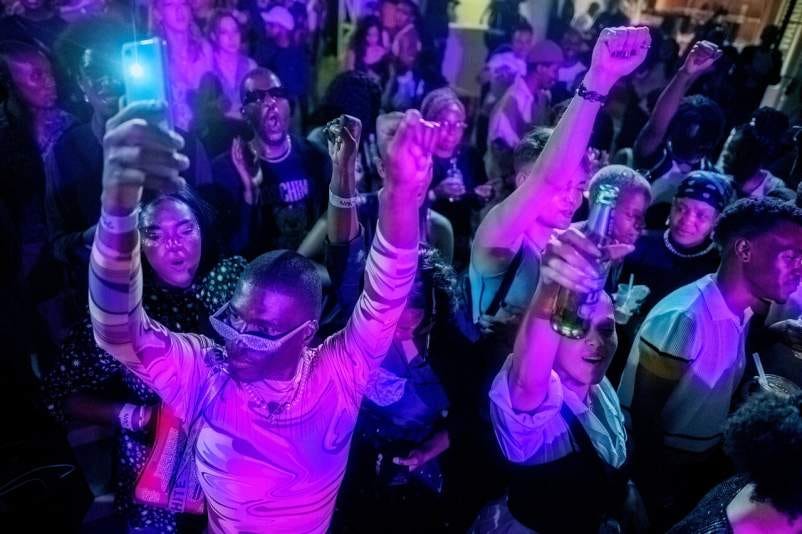

People dance by the stage of The Nest club during the Vogue Nights Jozi Ball, an event dedicated to the gender-fluid culture in Marshalltown, Johannesburg on September 24, 2022. Photo: Getty Images/Luca Sola

Prior to Afrobeats’ ascension, many queer artists across sub-Saharan Africa struggled to gain recognition in mainstream media due to the cultural taboos and stigmas associated with homosexuality. However, many are now using its popularity to gradually build their own platforms and develop niche communities.

When Cape Town rapper Angel Ho entered the music scene in 2014, intent on upstaging the status quo as an openly trans woman, she was admittedly at a predisposed disadvantage. But a few years later, when the ‘Afrobeats Wave’ started gathering momentum, she used it to promote her solo music. Angel Ho says that following the release of her single “Divine Feminine," she began to reach new audiences and gain the essential financial support that she needed. The song uses a mix of hip-hop, defiant chants, and an auto-tuned chorus to elevate the daily experiences of a trans person who is committed to not simply surviving, but thriving. And though Angel Ho had sung about her experiences before, what took her to the next level this time was a connection to online communities and a trippy Afrobeat backbeat.

On TikTok―where the hashtag Afrobeats has over 6 billion views ―singers connect with fans and share their music and art directly, while bypassing traditional gatekeepers like record labels and radio stations. That access has helped democratize the industry and allowed more diverse voices to be heard. But even as Afrobeats has helped break down barriers, in accordance with openly regressive cultural norms, many of the genre’s mainstream artists write coded lyrics that are sexist and homophobic, making it difficult to function if one’s identity does not align with patriarchy.

Austin Chimano, one of the stars of Kenya’s top band Sauti Sol, released “Friday Feeling” in 2021, a standalone solo single and coming-out mantra that also celebrated the country’s queer, underground ballroom culture. Chimano acknowledges feeling afraid of singing about his sexuality. However, he received support from fans and the general public, with many citing his bravery in speaking up and owning his truth. Chimano credits TikTok with helping his cohort of queer artists reach new audiences and shift perceptions.

Being in this industry, I constantly felt the need to suppress my sexuality for fear of repercussions and alienation. But nowadays, I see younger ones becoming vocal about these issues. If you had told me this would happen five years ago, I wouldn’t have believed you. I know this is because there’s a listening ear for them, not just at home but across the continent too. -Austin Chimano

But even as renown brings a measure of success, struggles remain. For instance, many artists in Togo, Mali, and Tanzania continue to fight to be seen within their heteronormative-dominated markets. And even artists who are successful have to contend with the threats of homophobic violence without support from their labels. That may be why so many queer artists have decided to go independent.

Ghanaian singer-songwriter JOJO Abot―whose music fuses Afrobeats with jazz, soul, and electronic music―shares this sentiment and speaks to it directly in their recent single “Gods Among Men,” an exploration of queer dysphoric experiences. But they say that shrinking down is not the answer.

It’s important for Black queer people to be aggressive with their voices. Prior to joining the music scene even as an indie artist, I’d been told that I wouldn’t be able to survive because nobody in the local scene would give me a chance; I’ve been ostracized by my peers and struggled to boost my music career financially. It wasn’t until recently that things started to turn around. -JOJO Abot

Photography: Fanny Viguier

Despite being started amid the uncertainty of 2020, Burning Womxn is a collective in Paris, France, with a fiercely tenacious and vibrant egalitarian spirit. An intersectional, volunteer-run festival, the annual arts weekender aims to create greater access for women and underrepresented genders in the creative industries by providing opportunities for like-minded individuals to meet, connect and collaborate.

When art director and designer Marion Degorce met teacher and art historian Julie Dentzer and musician Marie de Lerena in January 2020, the trio knew they wanted to push their activism in a new direction. The full extent of the collective’s multidimensional vision will be on display this weekend, as Paris’s la Bellevilloise hosts the second iteration of their festival. With no one medium taking primacy over the other, there’s a wide breadth of unbridled creativity on display. Visitors can also dip in and out of a craft fair and marketplace featuring everything from zines to queer horticulture as well as pop-up tattoo shops, makeup and nail art stalls, and a visit from the travelling, Monique Wittig-referencing feminist library Les Guérillères.

The Burning Womxn team are fully aware of just how vital spaces like theirs are in the wider festival scene – it sets a much–needed example.

We are seeing more and more initiatives that have similar intents [as Burning Womxn], but we need as many as we can. The vast majority of spaces are still not necessarily safe for the LGBTQIA+ community or marginalised genders. -Julie Dentzer

The committee strives to integrate an intersectional ethos at each level, whether it’s the welfare of artists or of festival-goers. From diverse programming and ensuring that artists are fairly reimbursed, to gender neutral toilets and a calm room to help support neurodiverse individuals in attendance, Burning Womxn aims to be structurally accessible and fair. The festival also implements extensive safeguarding around sexual violence which begins at the committee level and filters down from there.

Samiha Hossain (she/her) is a student at the University of Ottawa. She has experience working with survivors of sexual violence in her community, as well as conducting research on gender-based violence. A lot of her time is spent learning about and critically engaging with intersectional feminism, transformative justice and disability justice.

Samiha firmly believes in the power of connecting with people and listening to their stories to create solidarity and heal as a community. She refuses to let anyone thwart her imagination when it comes to envisioning a radically different future full of care webs, nurturance and collective liberation.