Global Roundup: Brazil Black Woman on Supreme Court Campaign, Queer Ghanian Pursuing Justice, S.Korea ‘Anonymous Birthing’ Bill, LGBTQ+ Indian Community, Japan Feminist Scholar Inspires Women in China

Curated by FG Contributor Samiha Hossain

A still from Everyone Has a Dream, part of a campaign to persuade President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to nominate a Black woman to the supreme court. Photograph: IDPN campaign/YouTube

Brazilians are pushing to make the dream of a Black woman on the supreme court a reality.

A short film, Everyone Has a Dream, released as part of a campaign calling on President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to nominate the first ever Black female justice to Brazil’s highest court includes a scene where a young Black Brazilian girl dreams of being a pop star, a writer or a world champion in gymnastics, dressing up like the Afro-Brazilian women who have achieved that before her. But when her mother suggests that she aspire to become a judge on the supreme court, the girl looks incredulous and asks: “Like who?”

It’s absurd to think that in a country that is more than 50% Black, and where Black women are almost a third of the population, there has never been a Black female justice. -Tainah Pereira, political coordinator of Black Women Decide

As the highest judicial authority in the country, Brazil’s 11-member supreme court acts as defender of the constitution. It is also responsible for trying nationally elected politicians and serves as the court of last resort for appeals. In recent years, it has acted as a counterweight to a conservative congress on issues such as Indigenous and LGBTQ+ rights and played a vital role in keeping former president Jair Bolsonaro’s authoritarian tendencies in check.

As well as an email petition that has garnered over 30,000 supporters, the publicity campaign has taken the Afro-Brazilian movement’s demand for a Black female justice to billboards in New Delhi and Times Square in New York.

It’s the first time that Brazil has spoken so much about how we need to see a Black woman in the supreme court, and that has to be reflected in our actions. Black girls in this country don’t even have the right to dream and think about being a justice, due to the absence of a Black woman in the history of the supreme court. -Karen Custódio, Institute for the Defence of Black People (IDPN)

There was hope of change after Lula was elected on a progressive platform last year, bringing an end to Bolsonaro’s openly racist and misogynistic reign. But activists feel that the government’s commitment to tackling Brazil’s deeply embedded racial inequality is stronger on paper than in practice. So far the president has not engaged with the campaign, nor its calls for him to meet some of the women the civil rights movement would like to see don a black robe. On Monday, he told journalists that race and gender would not factor in his decision.

Black Star Square, Accra Ghana. Ifeoluwa. A/Unsplash

Queer Ghanaians are often dissuaded from pursuing justice for hate crimes as they face discrimination and a corrupt system, however, one queer Ghanian is not backing down. Timothy, a 22-year-old queer man from central Ghana, had been the victim of a violent hate crime in April. The attackers beat and robbed him and also pressured him to organise a ransom from his family. Timothy reported it to the police and refused an out-of-court settlement. Three suspects have pleaded not guilty to the attack and are awaiting trial.

Ghana’s queer community fears a prospective anti-LGBTIQ law currently before Parliament for consideration will legalise the hostility and violence it has faced for years. The Human Sexual Rights and Family Values Bill has already attracted public support from legislators and is likely to become law in 2023 or 2024.

The police service has been accused by the Ghana’s Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice of discriminating against queer people. In 2020, for example, 16 of the 38 incidents of anti-LGBTIQ abuse reported to the commission were against the police, including for blackmail, extortion and physical or verbal assaults. There have also been accounts of victims who do not report cases because they want to keep their sexuality out of the limelight.

The director of advocacy at the Ghana Centre for Democratic Development, Kojo Asante, has been critical of formal processes at Ghana’s police stations because they offer no protection to queer people filing complaints. Asante has been part of a group of activists advocating systemic reforms within the police service to make it easier for members of the LGBTIQ community to report crimes against them. They have gone as far as petitioning Ghana’s inspector general of police, as well as sending compiled evidence of hate crimes for investigations. The group of activists (who wished to remain anonymous) helping Timothy with legal processes have complained of hurdles in the background, like fees being requested from victims to process certain documents that are supposed to be covered by the judicial system.

If this [anti-LGBTIQ] bill comes into play, look, there will be more extortion than justice. We are very hopeful of justice in [Timothy’s] case. We need something like this to shake things for the better in Ghana’s queer community. -Activist in the group

A “baby box,” where mothers can leave unwanted children, is visible on the left at Joosarang church as a preacher and two children go for a walk in Seoul, South Korea, September 20, 2012. © 2012 Kim Hong-Ji/Reuters.

South Korea’s National Assembly is rushing to approve a bill that would allow women to give birth anonymously at medical facilities. The bill, which pledges to protect women and children by tackling the issue of unregistered births, fails to address major factors that drive the incidence of births being unregistered, such as poverty and the stigma of single motherhood, according to an article on Human rights watch’ site..

In South Korea, a birth is “unregistered” when a child is born but not reported to the local government. In June, the Ministry of Health and Welfare disclosed that 2,123 unregistered babies born in medical facilities between 2015 and 2022, were never registered by their parents.

Women’s rights groups said, “most unregistered births result from patriarchal laws and systems, culture, and socioeconomic conditions,” and that South Korea’s woefully inadequate sexuality education and barriers to accessing abortion, though decriminalized in 2021, remain. The government also intends to abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, despite data showing that South Korea is lagging behind globally on women’s rights.

The article asserts that the bill would simply perpetuate stigma around single motherhood by offering anonymous births and child transfers as solutions to unwanted pregnancies and poverty, rather than addressing the needs of single mothers. It urges the government to take genuine measures to support women and children by ensuring access to comprehensive sexuality education and safe abortions, as well as childbirth and childcare. In addition, it calls for combating the stigma single mothers and children with disabilities face.

Participants dance during Delhi Queer Pride March, an event promoting gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender rights, in New Delhi, India, January 8, 2023. REUTERS/Adnan Abidi

Five years after a historic ruling to decriminalise same-sex relationships, life for many LGBTQ+ Indians in smaller towns and villages is starting to change. The 2018 ruling by the country's Supreme Court to decriminalise homosexuality opened the door to love for millions of LGBTQ+ Indians.

Hemant Kumar dreams of living a simple life - with a loving husband, daughter and all the respectability that comes from being an old-fashioned family man in small-town India.

Five years ago, Kumar thought that was just a pipe dream. Now the 21-year-old student dares to dream of finding love, living openly with another man, and raising a child together - all free from fear.

From my childhood, in my family and in my society, everyone has a family. So inside myself there is a father who wants a kid. -Hemant Kumar

But while the law is now on his side, homosexuality remains a taboo topic for many and discrimination persists in rural life. Moves at the national level may have started conversations about gay topics for the first time in smaller towns, but the pace of change remains slow, said Koyel Ghosh, managing trustee of Sappho for Equality, an organisation working for the rights of lesbians, bisexual women and trans men. Whatever progress may have been won in the courts or enjoyed in big cities, rural LGBTQ+ life remains unchanged for many, she said.

People are (still being) forced to be married off without their consent, they are being made to go through conversion therapy. When it comes to civil rights, when it comes to basic rights, I don't think there is much that there's being done. -Hemant Kumar

However, others, including Kumar, maintain that smaller cities and towns are seeing progress. For instance, Dozens of towns and cities far from India's big centres have launched Pride parades celebrating LGBTQ+ culture - Jamshedpur in 2018, Raipur in 2019, Palampur in 2021, Shimla in 2023. Souvik Saha, founder of the non-profit Jamshedpur Queer Circle, which helps young LGBTQ+ people in eastern India, says some schools are even exploring LGBTQ+ issues with students.

With one big battle won, the next focus for LGBTQ+ activists is legalising same-sex marriage, with a court ruling on the issue expected in weeks. Eighteen young couples have petitioned the Supreme Court to legalise same-sex marriage, said Meenakshi Ganguly of Human Rights Watch, a global NGO and advocacy group.

These are people who are seeking for their relationships to be legally recognised. While same-sex relationships are now more openly discussed in the media, and even in film and television shows, much more needs to be done to end entrenched discrimination. -Meenakshi Ganguly

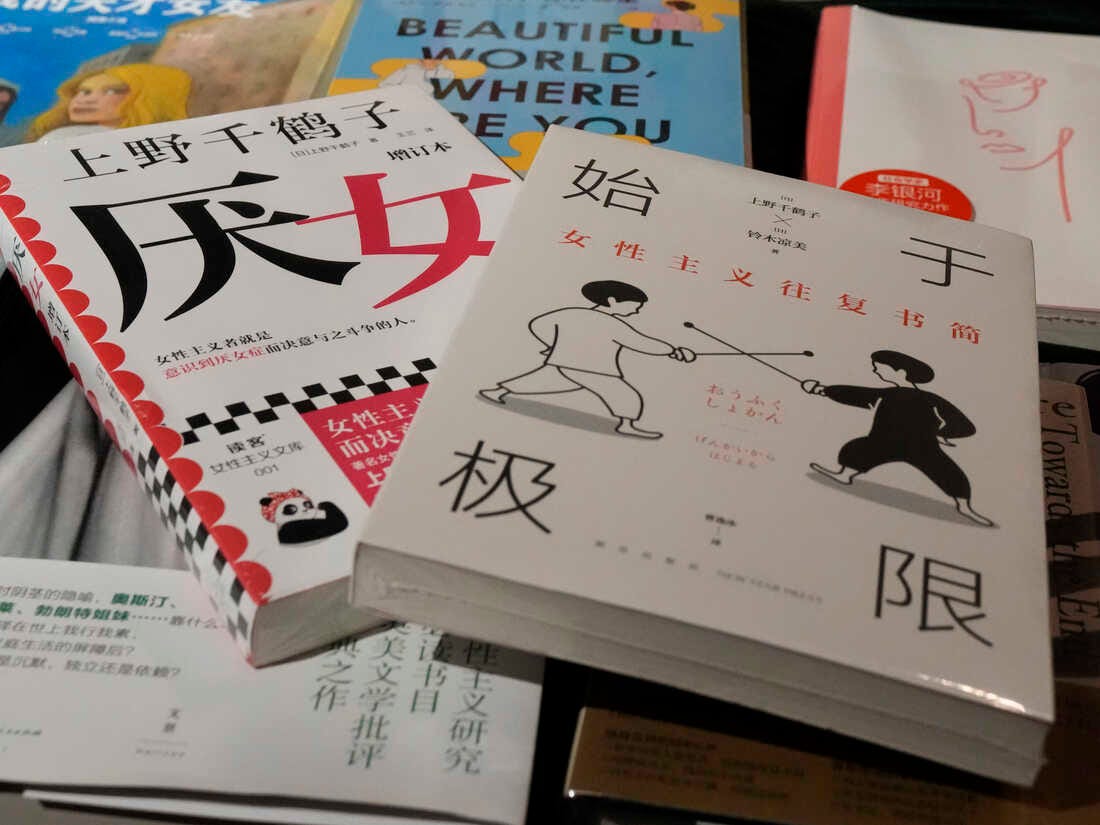

Books by Japanese scholar Chizuko Ueno at a bookstore in Beijing, Sunday, Aug. 20, 2023. "Misogyny" and "Starting from the Limit" are at the center. Ng Han Guan/AP

Chizuko Ueno, a professor emeritus at the University of Tokyo and feminist scholar, is a bestseller in China. Ueno leapt to fame in China in 2019 with a speech that criticized social expectations for women to act cute and the pressure they face to hide their success.

In the last few years, China's government has promoted increasingly conservative social values, encouraging women to focus on raising children. It has cracked down on civil society movements and made laws to drive out foreign influence. So a 75-year-old Japanese feminist scholar who's not married and does not have children is an unlikely celebrity on the country's tightly censored internet.

About a decade ago, China had a rambunctious feminist movement that staged protests like occupying a men's restroom to demand more toilets for women, or marching in wedding dresses spattered with fake blood to draw attention to domestic violence. But that movement has been silenced as President Xi Jinping's administration has tightened controls on civil society and promoted conservative family values in a bid to boost childbirths.

In mainland China, Ueno's books sold more than half a million copies in the first half of 2023, according to sales tracker Beijing OpenBook, and 26 were available in Chinese bookstores as of September. They cover topics ranging from "misogyny" in Japanese society to feminist approaches to elder care issues in an aging society. Fans said Ueno's openness about choosing not to marry or have children makes her a role model.

Protest and campaigning are no longer possible, said Lü Pin, a Chinese feminist activist based in the U.S., meaning feminism is confined to individual action and small groups. The Ueno boom, she said, has helped keep feminist ideas in the "lawful" mainstream. Megan Ji, a 30-year-old financial analyst, said it wasn't until she read one of Ueno's books that she began taking an interest in the ideas of feminists. That helped her confront her boss when he began caressing her back at an after-work karaoke party with colleagues and potential business partners.

Edith Cao, a writer who spoke on the condition of being identified by her English nickname due to fear of government retaliation, says there are problems that reading feminist books won't solve. However, she adds that "even if her words can't bring policy change [they] have further stoked an underlying force.”

Samiha Hossain (she/her) is an aspiring urban planner studying at Toronto Metropolitan University. Throughout the years, she has worked in nonprofits with survivors of sexual violence and youth. Samiha firmly believes in the power of connecting with people and listening to their stories to create solidarity and heal as a community. She loves learning about the diverse forms of feminist resistance around the world.