Global Roundup: Bulgaria LGBTQ+ Rights, Sudanese Women Activists, Muslim Women in Britain, Philly Queer Birding Group, China Women’s Secret Language

Curated by FG Contributor Samiha Hossain

People take part in Sofia Pride, June 2024. Photo: EPA-EFE/VASSIL DONEV

Bulgaria has passed a law banning LGBTQ+ "propaganda" in schools, in a new blow to human rights that advocacy groups and campaigners have widely condemned. The amendment to Bulgaria's education law, voted through by parliament on Wednesday, bans the "propaganda, promotion, or incitement in any way, directly or indirectly, in the education system of ideas and views related to non-traditional sexual orientation and/or gender identity other than the biological one."

The law has sent shockwaves throughout Bulgaria, prompting protesters to take to the streets and human rights groups to slam its progression through parliament. Activists and organisations such as LevFem, Feminist Mobilisations, and the LGBTQ+ organisation Action rallied under the slogan "School for all! Let's stop the hate!".

The wording of the law is reminiscent of Russian and Hungarian anti-LGBTQ+ propaganda laws, according to EU-wide LGBTQ+ advocacy group Forbidden Colours, suggesting it is an attempt by the Bulgarian government to suppress the visibility of LGBTQ+ individuals and push back human rights.

In 2021, the Hungarian government led by Prime Minister Viktor Orbán's Fidesz party amended its law on paedophilia and on the protection of children to limit their exposure to material "promoting homosexuality", gender reassignment, and LGBT representation in the media or public space. Violations of the law are punishable with fines or prison sentences. Amnesty International said earlier this year that the Hungarian law has "created a cloud of fear" that has pushed LGBTQ+ into the shadows, and the worry now is that the same thing will happen in Bulgaria.

Campaigners are calling on the EU to do more to clamp down on discriminatory measures against LGBTQ+ people among its members.

The European Union cannot stand idly by while one of its member states enacts laws that endanger the safety and rights of LGBTIQ+ individuals. -Forbidden Colours

Sudanese refugee children and their mother register at UNHCR Egypt after the fleeing conflict in Sudan. (©UNHCR/Pedro Costa Gomes)

After a whole year of war, women human rights defenders in Sudan continue to try and help those who are suffering. The Africa Report shares stories of several women activists.

Wassal Hamad al-Nile, a university student and activist, was forced to leave her home in Khartoum’s Bahri neighbourhood. Al-Nile and her family did not have enough money at that time, so her mother had to sell all the jewellery she had, for a pittance, to buy bus tickets to Shinde. She says the shelter they stayed at lacked basic necessities and was unsanitary and overcrowded with inadequate ventilation. She had been trying to help others there, by providing assistance and psychological support to women and children but was harassed by the authorities.

I was bullied, and we volunteers were called names by them and by some who were war advocates and those opposed to peace. -Wassal Hamad al-Nile

Nahla Youssef, head of the Coalition of Women Human Rights Defenders in Darfur, fled the city of Nyala with her 11-year-old son. They went through Juba before settling in Kampala, Uganda. Youssef describes how difficult and dangerous it was getting out. Now, in Uganda, she continues her work in assisting women human rights defenders.

In Sudan, extensive violations of human rights and international humanitarian law were committed, so my colleagues in the coalition and I continue our work and will not stop. -Nahla Youssef

Khartoum was tense before the large-scale mobilisation, and Hajar Mahjoub, a feminist activist and researcher, says she was unsure of how to keep the family together. Finally, she decided to leave with her five children for Abu Usher in Gezira State in central Sudan, some 110km southeast of Khartoum. But on the way there, they were subjected to humiliation and harassment at numerous checkpoints. Yet after getting to Gezira, Majoub was forced to leave again after the RSF took over the city, as she feared for her life and that of her children. But these harsh experiences have not prevented them from supporting their communities.

Despite the stress and oppression caused by the war, I [still] help women and children with disabilities, as this is my specialty and work that I have been doing for years. -Hajar Mahjoub

Human rights defenders are often targeted, which forces them to hide and reduce their movement or change their place of residence for fear of arrest or death. Youssef says many other women human rights defenders are subjected to bullying and smear campaigns on the Internet as a result of their demands to stop the war, while others have been killed. One of them is Bahjaa Abdelaa Abdelaa, who before her death, had been sent death threats for monitoring rape cases.

Photo: Furvah Shah

Last Monday, three children were killed in Southport, Merseyside, in an attack at a Taylor Swift-themed dance class. In the following days, misinformation began to spread online about the killer being a Muslim refugee who arrived to Britain by boat. Far-right rioters attacked businesses, homes and a mosque in Southport. Since then, riots have rapidly spread to other towns and cities, with agitators belonging to groups including the English Defence League, spewing anti-immigrant, racist and Islamophobic hatred. Businesses have been looted, people of colour have been randomly attacked, and a hotel housing refugees in Birmingham was set on fire.

In general, I remain vigilant on a daily basis. I stand away from the edge of the train platform, I avoid walking alone at night, and I have responses memorised for if, likely when, someone verbally attacks me because of my race or faith. At times like this, wearing the hijab feels like a target on my head. I feel increasingly unsafe and unprotected in the country I call home. -Furvah Shah

Shah criticises the lack of condemnation and action from politicians and news outlets, noting that it took six whole days of rioting for Prime Minister Keir Starmer to make a statement on the matter. She adds that some publications are still addressing the current unrest as “protests” even though they are clearly riots.

Being a person of colour in Britain right now feels bleak. It's exhausting – cancelling or changing plans because you're worried to go outside. Checking in on loved ones to make sure they are safe. Signing up to self-defence classes in order to best protect yourself. Never letting your phone battery fall too low in case of an emergency. -Furvah Shah

Despite being exhausted from the extra steps Shah must take in order to feel more safe, she finds solace in the rising counter-protests. She mentions locals helping clear up the remnants of protests in Southport and rebuild the attacked mosque as well as people using their voices online.

Elise Greenberg, one of the founding members of Philly Queer Birding, bird watching at John Heinz Refuge in May 2024.Erin Reynolds

Philly Queer Birders (PQB) is a group for Philadelphia’s queer community and its allies to get together and learn how to identify birds. The group is open to all, whether you’re an expert birder or it’s your first time with a pair of binoculars.

We always welcome a lot of beginners and a lot of experts alike. It’s just a really welcoming space. -Elise Greenberg, one PQB’s founders

The group birds throughout the city and region, at sites like Cobbs Creek, Tyler Arboretum, and, most frequently, John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum. John Heinz is the country’s first urban wildlife refuge and is home to several different environments, like woods, wetlands, and the creek, meaning visitors will see birds ranging from snowy egrets to marsh wrens, and other species including musk turtles and tricolor bats. Greenberg explains how it’s close to the city and yet does not feel like the city – a type of space Greenberg wanted to share with the queer community.

Greenberg and a few friends organized PQB and its guided bird walks in 2021. The group has grown significantly since then, and some walks have had up to 60 attendees, though they usually tend to pull around 35 people. Dani Gonzalez, a member of the group, says PQB is one of the few intergenerational queer spaces they have, allowing them to find role models within their community. Gonzalez shared that they tend to get emotional in intergenerational queer spaces because media representation of the LGBTQ community tends to skew tragic or have stereotypical tropes.

I love waking up early and being outside with my queer community. I love seeing happy, queer families and queer couples out birding. -Dani Gonzalez

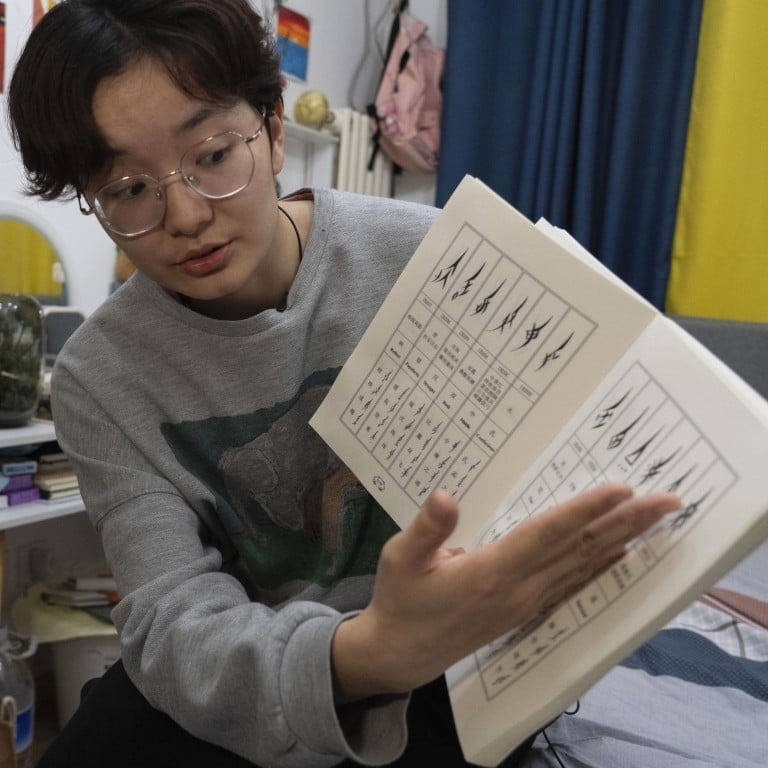

Lu Sirui talks about nushu, a centuries-old secret script which is empowering young women in China even today. Photo: AP

Chen Yulu, 23, is a self-proclaimed ambassador of nushu, a script once known only to a small number of women in central China. It started as a writing practised in secrecy by women who were barred from formal education in Chinese. Now young people like Chen are spreading nushu beyond the women’s quarters of houses in Hunan’s rural Jiangyong county, whose distinct dialect serves as the script’s verbal component.

Nushu was created by women from a small village in Jiangyong, in the south-central province where late Chinese leader Mao Zedong was born, but there is little consensus on when it originated. Scholars estimate the script is at least several centuries old, from a time when reading and writing were deemed male-only activities. The women developed their own script to communicate with each other. They lived under the control of either their parents or their husband, and used nushu, sometimes called “script of tears”, in secret to record their sorrows: unhappy marriages, family conflicts, and longing for sisters and daughters who married and could not return in the restrictive society.

The script became a unique vehicle for composing stories about women’s lives, typically in the form of seven-character line poems that are sung. A secret world sprang from the script that gave Jiangyong women a voice through which they found friends and solace. That secret world still resonates today as a source of strength for young women dissatisfied with patriarchal constraints.

Chen, who studied photography at an art school in Shanghai, said her male professors often doubted that she could keep up with the male photographers because of her slight physique. That attitude, she said, is “in every aspect of life, there’s nowhere it doesn’t touch”. She was frustrated but did not see much room to retaliate – until she learned about nushu. It led her to create a documentary about the script where she follows He Yanxin, a formally designated inheritor for nushu who is now in her eighties.

I felt that I had received a very strong power, and I think a lot of women need this power. -Chen Yulu

Beginning in 2022, Chen began spreading the practice. She started an online nushu group, taught writing workshops and set up nushu art exhibitions in cities across China. Most participants at her writing workshops are women, she said, and some people even bring their mothers. Chen also runs a social media account to promote nushu and its culture beyond Hunan. Lu Sirui, a 24-year-old working as a marketer, joined Chen’s nushu-focused group and now hosts nushu workshops herself at bookstores and bars in Beijing.

At first, I just knew that [nushu] was a women’s inheritance, belonged only among women. Then, as I got to know it better, I realised that it was a kind of resistance to traditional patriarchal power. -Lu Sirui

Thank you for reading Global Roundup. You can support FEMINIST GIANT by:

Hitting the heart button so that others can be intrigued and read

Upgrading to a paid subscription to help keep FEMINIST GIANT free

Opting for a one-time payment via buying me a coffee

Sharing this post by email or on social media

Samiha Hossain (she/her) is an aspiring urban planner studying at Toronto Metropolitan University. Throughout the years, she has worked in nonprofits with survivors of sexual violence and youth. Samiha firmly believes in the power of connecting with people and listening to their stories to create solidarity and heal as a community. She loves learning about the diverse forms of feminist resistance around the world.