Global Roundup: Dalit Women Journalists, Supporting Women Migrant Worker Survivors, Tunisian LGBTQ Community, Malawi's Youth Radio Show, Ghanian Artist Subverting Discourse on Queer Africans

Compiled by Samiha Hossain

‘These journalists are holding people accountable …’ The journalists from Khabar Lahariya. Photograph: Courtesy of Sundance Institute via The Guardian

A documentary called Writing with Fire has been released on Khabar Lahariya, India’s only all-women news organization based in Uttar Pradesh. It began as a temporary project funded by an NGO to train women in a village to write a newsletter. Today, the journalists – the majority of who are Dalits, the lowest status in India’s caste hierarchy – report on rural issues from a feminist lens. They shed light on the voices missing in mainstream media.

The documentary was filmed over 5 years by Rintu Thomas and her husband Sushmit Ghosh. It focuses on three women working at the organization: a chief reporter who insisted on finishing her education after marriage at 14; a domestic violence survivor; and a journalist who worked in an illegal mine as a child.

Men in positions of power are used to seeing Dalit women cleaning their toilets. They’re not used to seeing them with mobile phones, challenging them about accountability and governance. It stumps them. - Sushmit Ghosh

Khabar Lahariya goes beyond simply writing stories. The editorial policy requires journalists to follow up every article after four weeks and if authorities do not take action, they write a follow-up story, tagging district officials on social media. This approach to accountability has led to electricity coming to a remote village, schools built, roads surfaced, and men being arrested and jailed for rape.

In Indian society, you don’t talk about things that bring shame to the family, shame for yourself. So the consensus is: let’s hush it up. We need to reconsider whose shame [it is]. And that’s what the feminist lens is; you’re able to think differently from the way you’re trained to think by your family, your community, your society… Men are like: ‘Why are you talking about this?’ But having these conversations will take us forward as a society. - Rintu Thomas

Doing this work is by no means easy – the journalists have received death threats and have had mobs show up to their homes. They are also subject to social media trolling. It is unsurprising that the patriarchy is threatened by the noise these women are creating and how they are refusing to give up on issues until they see accountability and change.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

San May Khine organizies a session on violence against women migrant workers, trafficking in persons and the rights of women migrant workers in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Photo courtesy of San May Khine via UN Women

San May Khine is a social worker in Thailand who was once a migrant worker and is now supporting other women migrant workers to cope with their past experiences of violence. Khine says she was exploited as a domestic worker in Myanmar and she was unaware of the little rights she did have. She was able to earn money in Thailand, which gave her more freedom. Migration also allowed her to leave her abusive husband. Khine’s experience made her realize she wanted to support the migrant community to break free from gender-based violence.

I thought only men could do things like protect the family and earn money – the traditional roles of the father. My daughter was very little, and I was terrified to leave my husband, so I endured his abusive words and acts. But, one day, I realized that I was working like he did, earning money like he did, and I was protecting my daughter, probably better than he did. - San May Khine

Khine is now part of a multi-disciplinary team in Chiang Mai province that has a large migrant population from Myanmar. She works with migrant women and their children who have experienced violence and trafficking.

I see my past in them. I know they have unlimited, yet unrealized, potential because of what women are ‘supposed to be’. While the COVID-19 pandemic is a difficult time for everyone, it is extremely difficult for women who have had to stay within abusive relationships. I’ve seen an increase in the number of cases of violence, and also an increase in the intensity violence. - San May Khine

Khine’s work is supported by the Safe and Fair Programme, jointly implemented by UN Women and ILO, in collaboration with UNODC, as part of the multi-year EU-UN Spotlight Initiative to Eliminate Violence Against Women and Girls. The programme recognizes that it is important to work with those with lived experience, as the research shows that women migrant workers who are survivors of violence tend to seek immediate support from friends, fellow women migrant workers or local civil society organizations.

It is heartbreaking that so many women migrant workers have had to escape from violence and horrific conditions. Even as migrant workers, they are vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. Khine is determined to keep working until “every woman and girl is free from violence and trafficking.”

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

AMANI MKAOUER. ALL PHOTOS: PAU GONZÁLEZ via VICE

Earlier in the year, LGBTQ groups joined a wave of mass protests across Tunisia demonstrating against police brutality and widespread unemployment triggered by the pandemic. A subsequent Human Rights Watch report documented dozens of cases where police were specifically targeting known LGBTQ activists, subjecting them to arbitrary arrests, physically assaulted individuals, blocking them from receiving legal aid, and threatening to rape and kill individuals. There were also cases of online harassment and the “forced outing” of activists.

Ahmed El Tounsi, the founder of the trans-rights organization OutCasts, has experienced increased mistreatment at the hands of Tunisian security forces over the last year.

Being a well-known trans person leaves me vulnerable to more abuse. The police know where I live, since the beginning of the pandemic they’ve been carrying out raids on my home regularly as I’m hosting lots of trans people. - Ahmed El Tounsi

Following a violent incident with the police, activists filed a complaint seeking to hold the police officers accountable, but the courts refused their request to review nearby CCTV footage. Several lawyers involved in the case appealed in late October and are awaiting a final decision.

The lockdown has created additional stressors for El Tounsi including being unable to find stable work or receive hormone injections. Over the past year, he has provided refuge to anything between two to 11 people at a time in his one-bedroom flat, while himself struggling to pay bills and provide food. He says some days he gets over 50 phone calls a day from trans men and women asking for help.

Amani Mkaouer is a 26-year-old human rights activist who facilitates workshops on gender identity and women’s sexual health and rights. The pandemic restrictions have meant that she’s trapped with her family getting comments on her gender expression, with no other place to go. The few LGBTQ-friendly locations that did exist are currently closed.

In Tunisia, same-sex relations are illegal and punishable by up to three years in prison under article 230 of Tunisia’s penal code while article 226 penalises “attacks on public morals” and "public indecency". These two articles allow to prosecute and convict people on the basis of their non-normative appearance or behaviour. Activists continue to fight for the decriminalization of same-sex conduct and identify protecting the members of the community as a key priority. When we think about the impacts of the pandemic, we cannot forget marginalized communities who experience increased barriers and discrimination.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Doreen Sakala poses for a photo with her baby at Mudzi Wathu radio station in central Malawi, May 20, 2021. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Charles Pensulo

The "Let's Shine" radio program is made by and for young people in Malawi covering culturally taboo topics including sexually transmitted diseases and contraception. About 400 youth reporters have been trained to research and host radio shows in nine stations across the country. The idea is to go beyond training the reporters on journalism and equipping them with important life skills to become role models for youth in their communities. The radio show has been estimated to have reached three million youth since it launched in 2017.

The chief of Nzenje village near the Zambian border said teen-led radio shows have contributed to the dissolution of six child marriages, with another three currently in the process of being dissolved. Though child marriages are illegal in the country, convictions are rare, and the practice remains common. Since the pandemic, teenage pregnancies, child marriages and sexual violence have been on the rise.

Doreen Sakala became pregnant at 15-years-old and says hearing young people discussing the educational challenges faced by pregnant teenagers helped her. Today, she dreams of training to become a doctor.

Listening to the radio opened up my eyes to the opportunities I can have if I work hard in school… I want to finish my education ...(so I can) assist my baby and people in my community. - Doreen Sakala

“Let’s Shine” demonstrates the power of normalizing conversations that are traditionally considered private. It is uplifting to see youth leading this initiative and empowering other youth to challenge cultural norms.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

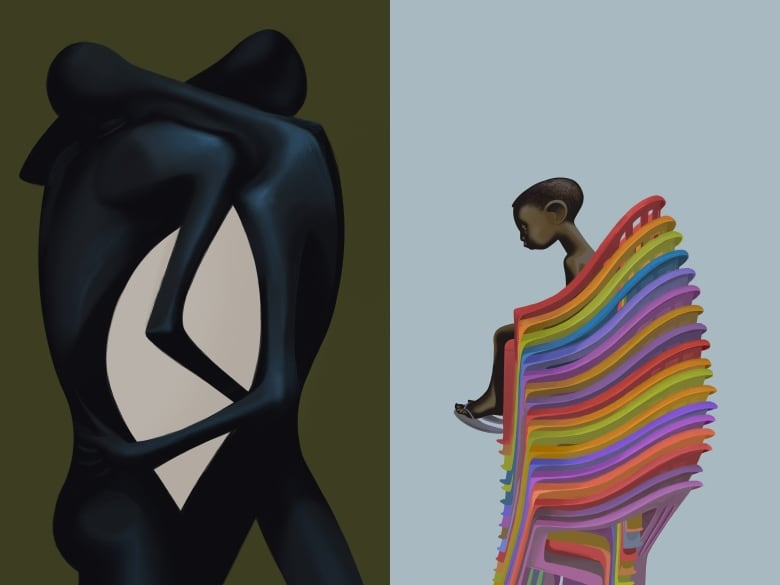

The two pieces Gyimah Gariba donated to the LGBT+ Rights Ghana fundraiser. Left: "Us." Right: "Throne." (Gyimah Gariba) via CBC

Last week, a draft of a draconian anti-gay bill was submitted to Ghana's parliament proposing a 10-year prison sentence for citizens who identify as LGBTQIA+, which would further criminalize the community.

Gariba has collaborated with artists in the diaspora to bring light to a recent violent raid by Ghanaian police to defund the organization LGBT+ Rights Ghana. His two most recent pieces were included in a locally curated art fundraiser to raise money for a new space for LGBT+ Rights Ghana.

In an interview with CBC, Gariba discusses his two recent pieces and how he sees them provoking conversations about sexuality in Africa and how people can channel their empathy into direct action.

Gariba says that as he gets older, he finds it more difficult to separate his politics from his art. Now, he tries to be more deliberate about the message to be reflective of who he is.

Going back to what I was saying about trying to be myself everywhere — I don't think that's possible right now. I['m] Black, gay, [and] dark-skinned, and there's so many more [points of identity] that I don't even experience [that others do]. What would it be like if we didn't have all these obstacles all the time? What does that space look like? What does it look like to feel that? It's the same thing [as] a little kid [asking me]: Can you draw me as a Black panther? They need to feel big, stronger, better. I'm asking myself, Can you draw yourself without these limitations? What does that look like? Can you give yourself a map? - Gyimah Gariba

He also talks about using his artwork to challenge the notion that being queer is un-African. In his two recent pieces, he was inspired by sculptures from West Africa and how forms would be made out of one block of wood and interconnect. He wanted to take that and turn it into something that evokes tenderness.

Those are the things that I want to remarry, to bring closer together. What is African imagery? What is an African aesthetic? What are the things that are wholly in the arts through the West African lens, and how do I marry that with queerness? [In my work I'm] taking those ideas, and then slowly trying to make staples of imagery to make the point that you can be African and queer. It's alleviating that taboo by making it feel like it's historically accurate, because that's where people base themselves so firmly. I want to normalize the aesthetics of it so that it feels natural on every level. - Gyimah Gariba

—————————————————————————————————————

Samiha Hossain (she/her) is a student at the University of Ottawa. She has experience working with survivors of sexual violence in her community, as well as conducting research on gender-based violence. A lot of her time is spent learning about and critically engaging with intersectional feminism, transformative justice and disability justice.

Samiha firmly believes in the power of connecting with people and listening to their stories to create solidarity and heal as a community. She refuses to let anyone thwart her imagination when it comes to envisioning a radically different future full of care webs, nurturance and collective liberation.