Global Roundup: Femicide in France, Healing Centre for Activists in Honduras, LGBTQ+ Adoption in Taiwan, Women Changing Sumo Wrestling, Queer Youth in Nigeria Revive Ballroom Culture

Compiled by FG Contributor Samiha Hossain

Feminist groups say government efforts should focus more on prevention of violence against women Image: Sadak Souici via France24

CW: gender-based violence

Three women were murdered in suspected intimate partner violence attacks on New Year’s Day in France. Feminists say that the government is failing to protect women and not doing enough.

Police in Nice found the body of a 45-year-old woman in the trunk of a car after her husband turned himself in and confessed to having strangled her. On the same day, police in the Meurthe-et-Moselle region found the body of a 56-year-old woman with a knife stuck in her chest. Her partner admitted to killing her following an argument. And finally, a 27-year-old woman was found lying with fatal stab wounds outside her home in a town near Saumur. Her partner was arrested, and a murder probe has been opened. All these incidents took place within 24 hours.

Feminist organization Nous Toutes denounced "the silence of Emmanuel Macron and the government in the face of sexist and sexual violence in France." The outcry led to government ministers holding an online meeting with officials from the town where one of the killings took place. However, feminists believe it is not enough.

In 2022, there is no longer the time to lament, it is the time to act. These femicides could have been avoided. Three women killed in 24 hours and their only reaction is to organize a little meeting days later. No, their work isn't done. - Marylie Breuil of Nous Toutes

There were over 113 women killed by men in France in 2021. Despite the government setting up emergency hotline services, sensitivity training for 90,000 police officers and an “equality week” at school, women continue to be murdered at alarming rates. It is crucial that the government listens to survivors and feminist organizations and tackles the root causes so that women don’t need to be protected and can live without fear of violence.

Rebeca Girón, who runs La Siguata healing centre in Honduras, stands in the grounds, where the women can relax and connect with nature. Photograph: Jeff Ernst

La Siguata is a healing centre in Honduras for women who are suffering from trauma as a consequence of having stood up for human rights in the country. The 10-day retreat at La Siguata is part of a growing movement led by the Mesoamerican Initiative of Women Human Rights Defenders, which funds this and another centre in Mexico, addressing the mental health issues that come with working in one of the world’s most dangerous regions for activists and women.

We realised that there was lots of burnout and also strong impacts on women defenders as a result of structural violence, as well as patriarchal violence that was very invisible and normalised. The very demanding dynamics of women defenders’ activism means that we don’t have time to recover our energies, to connect with our bodies and needs. There is an imbalance between giving and receiving. - Ana María Hernández of Casa La Serena healing centre in Oaxaca, Mexico

Women take part in activities ranging from artistic to spiritual both individually and in groups. They are also given a personalized self-care plan to take home. The centre is open to survivors of sexual abuse and families of disappeared migrants as well. In the future, La Siguata hopes to host women from Nicaragua – where the government has brutally repressed dissent, resulting in hundreds of deaths.

We know that these 10 days are not going to be the 10 days that will transform their lives, with sudden changes from one day to the next. But we do consider that we open the way. La Siguata represents the recovery of that internal flame of passion, for wanting to live again and even to enjoy human rights work anew. – Rebeca Girón, of the National Network of Women Human Rights Defenders, who runs La Siguata

Those working in human rights are often overworked and deal with both their own and other’s trauma. This initiative is important in promoting self-care and ensuring that activists prioritize their own wellbeing.

Taipei Pride 2020, Taiwan. (LightRocket via Getty/ Alberto Buzzola)

Currently in the country, same-sex couples can adopt only when one partner is the biological parent of the child. However, in December 2021, a family court in Kaohsiung city ruled that 38-year-old Wang Chen-wei’s child, who he previously adopted, could also be adopted by his 34-year-old husband Chen Chun-ju.

Though it is a historic step for LGBTQ+ rights in the country, the ruling only applies to their specific case, and has not legalized same-sex adoption across the country.

I am happy that my spouse is also legally recognised as the father of our child… but I can’t feel all that happy without amending the law. It’s really absurd that same-sex people can adopt a child when they are single but they can’t after they get married. - Wang Chen-wei’s

The Taiwan Equality Campaign said that two other couples it supports had had their adoption requests rejected.

We hope the rulings serve as a reminder to government officials and lawmakers that the current unfair legal conditions need to be changed. - Jennifer Lu, executive director of the Taiwan Equality Campaign

Senna Kajiwara (center) started practicing sumo when she was eight years old via CNN

Professional sumo still excludes women from competition and ceremonies, and in recent years, several scandals have tarnished the sport's reputation, including in 2018 when female medics trying to help a collapsed mayor were ordered out of the sumo ring in Kyoto prefecture. However, experts say changing attitudes in Japan are paving a future for girls and women in sumo.

According to Eiko Kaneda, a professor at the Nippon Sport Science University in Tokyo, Japan, women's sumo has been around since the sport's early days.

Miki Ouike, a wrestling coach, takes pride in having so many girls in his class but says a general lack of sumo clubs across Japan means that many girls who do it train in judo and wrestling. He says that there still isn’t enough awareness about the existence of girl sumo competitions. Girls that want to try the sport, start by joining unisex sumo clubs and if they want to keep up, they join one of the handful of universities in Japan which welcome women in their sumo clubs.

Hiyori Kon, a member of Japan's national team, followed this path. Today, she works at a Japanese company in Aichi prefecture and competes internationally as an amateur female sumo wrestler. She wants more women to be able to keep up sumo but says that sometimes male coaches don't understand how to respond to aspiring women sumo wrestlers. At this year’s Wanpaku elementary girls’ tournament, Kon attended as emcee, providing commentary on the wrestlers’ techniques

Japanese society has become more supportive of women’s sumo. This is the second year we have held the ‘Women’s Wanpaku Sumo’ and I’m proud we went from zero, to one and now two tournaments. - Hiyori Kon

Kon ultimately dreams that women can have the option to earn a living from sumo, just like men.

Women's sumo is seen as a minor sport, and Japan's national women's team can't set up a training camp due to lack of funds. The main question is how can we establish a league and make amateur sumo professional. - Hiyori Kon

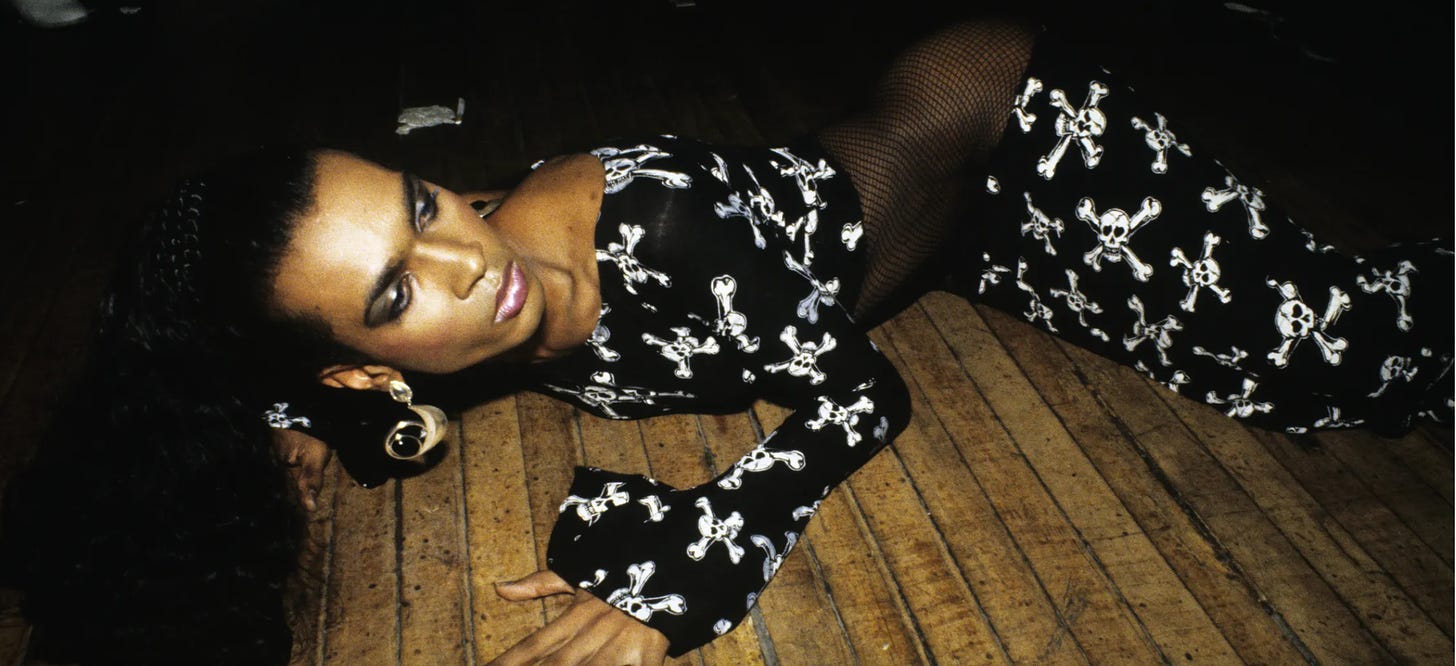

GETTY IMAGES via Teen Vogue

Though Nigeria’s ballroom culture has existed for years, it has been driven further underground due to stricter anti-gay laws. The country’s ballroom scene in the early 2000s was a way for queer people to connect with each other and express themselves freely through dance and fashion. The balls were a celebration of what it meant to be queer and Nigerian and a place for community and family, as many queer Nigerians were not supported by their biological family members.

The best thing about [the balls was the fact that you were with your people in a place where you did not have to perform heterosexuality or conform to gender norms and that is what community is. - Dennis Macaulay, a gay man in his mid-30s

The balls also became a place to provide aid to the queer community through HIV-related support, medical care, therapy, and support in cases of human right violations. It became a place of outreach and advocacy.

In 2014, the Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act (“SSMPA”) — which expressly prohibits the meetings of gay clubs, societies, and organizations, as well as the direct or indirect public show of “same sex amorous relationship” — was signed as law, and this led to an increase in violence against queer folks all over the country. The law made it even more difficult to organize balls and fear increased.

Thus, a lot of young queer Nigerians are unaware of the underground ballroom scene in their states. However, with the help of the internet and social media, the younger generation of queer Nigerians who do know about the ballroom scene are working to revive it.

Twenty-five-year-old Aaron Ahalu is an artist and rave organizer in the Lagos underground electronic scene who began organizing balls with a collective called the hFactor. He has successfully organized three balls in Lagos.

It is impossible to go anywhere in Nigeria and find men dancing together, holding themselves affectionately or even sharing a kiss in public. We are not allowed that freedom of expression here. I want to be able to have fun without any restrictions that prevent me from truly expressing who I am. Watching ballroom culture in [shows] like Pose and videos on YouTube made me thirsty for that level of freedom and drove me to start organizing mentally, somehow I was able to communicate with the right people and we had our first ball in July, just a week after pride month. - Aaron Ahalu

Young queer people in Nigeria do not want to conform. They want to live their lives unapologetically despite the danger that may entail. The ballroom scene helps these young queer people challenge homophobic. legislation and find community.

Samiha Hossain (she/her) is a student at the University of Ottawa. She has experience working with survivors of sexual violence in her community, as well as conducting research on gender-based violence. A lot of her time is spent learning about and critically engaging with intersectional feminism, transformative justice and disability justice.

Samiha firmly believes in the power of connecting with people and listening to their stories to create solidarity and heal as a community. She refuses to let anyone thwart her imagination when it comes to envisioning a radically different future full of care webs, nurturance and collective liberation.