Global Roundup: Feminists Advocate for Sudan, Decriminalizing Abortion in Brazil, Mexico Trans Textbook, India Woman Runner, Japan Trans Rights Advocates

Curated by FG Contributor Samiha Hossain

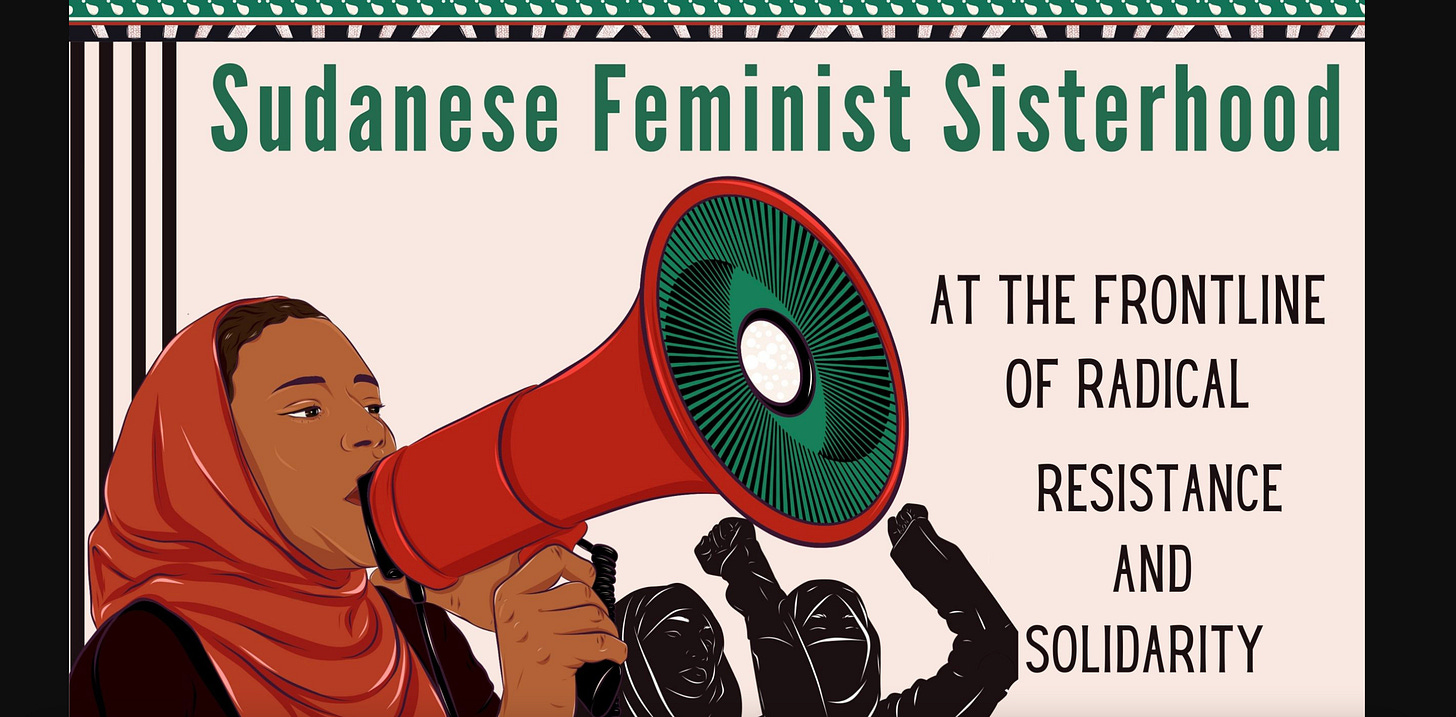

Image via Alliance Magazine

With the ongoing military escalation in Sudan, feminist groups and individuals are intensifying their appeals for an immediate resolution to the conflict. During a recent symposium organized by the Sudanese Women’s Union, a cohort of feminist activists illuminated the hardships faced by displaced women residing in shelter centres and the profound repercussions of the war on their lives.

Journalist Madiha Abdullah, in her presentation titled “Violence and Deprivation of Rights,” stressed the importance of the feminist movement prioritizing an end to the conflict and addressing the underlying causes of these injustices. Abdullah discussed topics such as how the conflict has pushed women into informal economic activities to make ends meet; the alarming surge in violations against women, including harassment and beatings by security personnel and police; the dire conditions in shelter centres, particularly for pregnant and breastfeeding women lacking adequate support; and the lack of access to essential resources such as clean water and sanitation facilities.

Sumaya Ali Ishaq, a member of the Executive Committee of the Sudanese Women’s Union, echoed these concerns, describing the situation of displaced women as “desperate” due to the spread of epidemics like dengue fever and cholera. Ishaq highlighted that women, far from being parties to the war, were the backbone of the revolution and should actively partake in decision-making processes within state institutions.

Aisha Khalil, another participant in the symposium, echoed the urgent need for women to unite and amplify their voices to end the war, which has resulted in widespread displacement and homelessness. She called for all factions to unite in forming a pressure group to bring the conflict to an end. Ihsan Abdel Aziz, representing the Women Against Injustice Campaign, called for more significant documentation of violations against women and the dissemination of accurate data to raise international awareness.

The symposium concluded with a renewed call for strengthening the women’s front against the war, advocating for intensified fieldwork, escalating public action to stop the conflict, and planning for a vision for the post-war era.

‘No hypocrisy - unsafe abortion kills the poor every day’ and ‘For women’s lives’. Signs held in support of legal abortion during a march in São Paulo, Brazil, on September 28, 2023. MIGUEL SCHINCARIOL/AFP via Getty Images

Abortion in the country is punishable by up to three years in prison, and is allowed on only three grounds: rape, risk to the life of the pregnant person, and – following a 2012 Supreme Court decision – when the fetus suffers anencephaly, a fatal birth defect. It seemed like change was finally on the horizon in September, when then Supreme Court president Rosa Weber, who was on the verge of retiring, opened a virtual plenary session and voted to decriminalize abortion within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. But soon after, Weber’s replacement as the court’s president, justice Luís Roberto Barroso, froze the virtual debate indefinitely. Some believe Justice Barroso’s postponement is strategic, as it’s unclear if there is a pro-choice majority within the 11-member court. His decision has been met with fury from women’s rights activists, who say women and girls cannot afford to wait any longer for safe access to abortions.

Today, one in every 28 women in Brazil who are admitted to public hospitals after having an unsafe abortion or due to post-abortion complications will die, according to research published by Gênero e Número, a data journalism outlet on gender and race. The risk is twice as high for women of color due to systemic barriers.

Those in power are held responsible for letting people die, for letting people suffer. These judges have to sign off this chapter of history. -Débora Diniz, founder of Instituto Anis de Bioética, a non-profit that works to defend reproductive and sexual rights

In 2020, a ten-year-old who had been raped was denied abortion care in São Mateus, a muncipality in north-east Brazil, even after securing permission from the courts to have the termination. She and her family were forced to travel to another city to get a legal abortion.

But the girl’s ordeal still wasn’t over. She was publicly exposed on social media, prompting religious fanatics to storm the hospital shouting ‘murderers’. The then-minister for women and human rights, Damares Alves, also dispatched members of her team to the scene to try to prevent the abortion.

Alves, now a senator, was a member of Jair Bolsonaro’s far-right administration, which introduced a series of measures to impede access to legal abortions. These included ordering health staff to call the police when a sexually abused patient requires a legal abortion and to offer the patient an ultrasound to “see the foetus or embryo”. Bolsonaro was defeated by leftist leader Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in the 2022 election but Brazil is still emerging from the consequences of his presidency.

For women’s movements in Brazil, Weber’s vote held promise after five years of silence. Now, many feel they are back to square one. Feminists argue that to now win change on abortion, the issue must be detached from the political discourses of moral panic and religious taboo. For Diniz, other Supreme Court justices must keep up Weber’s fight for decriminalization. Anything else, she said, would keep Brazil stuck in “a cowardly time” in which women “suffer and die”.

High school students are pictured in a classroom in San Nicolas de los Garza, Mexico January 30, 2023. REUTERS/Daniel Becerril

Mexican advocates want teachers to better protect trans and non-binary kids. When 12-year-old Daniel transitioned gender in middle school, his Mexican teachers had no clue what to call him, how he should dress or what on earth to tell his classmates. So they kept it all secret – prompting his mother to join a group that is backing a new text book for teachers on the dos and don'ts of trans life to ensure children like Daniel get the sort of help he never had.

They told me everything was fine but that they preferred that nobody knew (about the process of changing gender). You could tell they did not know what to do next. -Jennifer Blanco, Daniel's mother

The Association for Transgender Infancies (ATI) is looking to fill the blackhole of dis- and misinformation with their book of practical tips to help schools help pupils adjust. The guidelines establish the steps teachers and staff must take to provide trans and non-binary kids with a safe and happy school life. The goal is for the government to adopt their recommendations and roll them out nationwide, though the Ministry of Education has yet to reply to their request even as it reassesses sex ed.

The organization has already trained more than 70 schools – a drop in the ocean against a nationwide tally of 260,262 - and most of those only agreed to it after a judge mandated training after presiding over discrimination cases.

While the guidelines are yet to be officially adopted, the timing for new ideas is ripe given the government is actively looking to expand its education on sexuality and diversity. This year, Mexico launched a new curriculum for children aged six to 14, with textbooks using inclusive language and citing concepts such as gender identity and LGBTQ+ families. The new books were distributed in September to schools and promptly met with protests from parents and lawsuits by conservative groups, gaining traction in a country where LGBT+ issues divide Mexico's predominantly Catholic population. The protests, however, were dismissed by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador for their "backwards" thinking.

One of our main purposes must be for our students to have a space where they can feel free and safe – even from their own families. -Celene Avilés, teacher

In states such as Mexico City, local authorities are collaborating with the ministry on training.

Sony Rangel works with Mexico City's department of diversity and has trained teachers and parents from elementary school to high school; he has seen great openness – and fierce resistance.

A woman on an early morning run in Kolkata. Photograph: Bikas Das/AP

Sohini Chattopadhyay, award-winning reporter and film critic, and the author of The Day I Became a Runner, writes in the Guardian about how running is a way to challenge the patriarchal view of a woman’s place and claim a space in the public sphere.

Chattopadhyay discusses the effect the 2013 Delhi gang-rape had on her, when 23-year-old Jyoti Singha was gang-raped by six men on a bus and later died as a result.

The streets of the capital, and television news studios – particularly English-language ones – convulsed with palpable anger. My own response to the Delhi gang-rape was overwhelmingly physical. I wanted to go out and physically inhabit space. I am here, I wanted to say. Get used to me. -Sohini Chattopadhyay

Chattopadhyay started running in the park in her upper-middle-class government-built compound. Even within the security of the compound, she was the only woman who ran.

I noticed I never asked men to make way for me. Instead, I would stop running, sidle past, then run again. It disturbed my running rhythm, but what if they were annoyed by me asking them to move? I wore baggy T-shirts that I kept pulling down, and full-length bottoms – never shorts. I tried to make myself as inconspicuous as possible. I had internalised the patriarchal belief that women belong inside the home. -Sohini Chattopadhyay

However, slowly, running changed Chattopadhyay. It made her more aware of her body, its limits and strengths, gave her confidence, and made her more confrontational. Chattopadhyay says women’s status might be legitimate in the home, but not in the public sphere. She believes sport offers the legitimacy to cross the threshold because it is seen as (potentially) performing for the nation.

In her book, The Day I Became a Runner, Chattopadhyay travels the decades from the 1940s to the current moment through the lives of nine runners, and herself – a hobby runner. She says because running puts bodies on view, it is a more direct claim to citizenship – and a more defiant challenge to patriarchy.

A major publishing house in Japan has cancelled the publication of a translated version of Abigail Shrier’s anti-trans book, after a backlash and a planned protest outside its headquarters. The Kadokawa Corporation revealed its decision on Tuesday to suspend the publication of the Japanese version of Shrier’s Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters, saying the copy was hurtful to the trans community.

Irreversible Damage has courted controversy since its initial publication in 2020. The book proliferates debunked anti-trans theories that being transgender is a “contagion”, a “craze” and an “epidemic”. On X, formerly Twitter, there was a huge backlash against Kadokawa’s initial promotion of the book. Trans rights advocates planned a protest outside the publisher’s corporate headquarters in Tokyo, a move that has now been cancelled.

After the decision, one social media user wrote that while it was good that the book had been pulled, they worried that “future measures” to prevent similar incidents remain “unclear and unsatisfactory” so couldn’t be sure if Kadokawa’s apology to the trans community was genuine. Another account said it was “really important to speak up” against the book.

In October, more than 100 University of Virginia students stood outside an event where the author was appearing, chanting and holding up signs in support of the trans community. The chants were so loud that they could be heard from inside the venue, according to one reporter. These incidents involving the harmful book are an important reminder of the power of collective action and protest.

Samiha Hossain (she/her) is an aspiring urban planner studying at Toronto Metropolitan University. Throughout the years, she has worked in nonprofits with survivors of sexual violence and youth. Samiha firmly believes in the power of connecting with people and listening to their stories to create solidarity and heal as a community. She loves learning about the diverse forms of feminist resistance around the world.