Global Roundup: Indigenous Aymara Women vs GBV, Coerced Sterilization of Indigenous Women in Canada, LGBTQ2S+ Muslim Advocate, Pride and Immigrant Heritage Month, Black Queer Electronic Music

Compiled by Samiha Hossain

A Bolivian Aymara woman poses for a photograph while learning self-defence during a taekwondo class of the Warmi Power social project, on the outskirts of La Paz, Bolivia April 23, 2021. Picture taken April 23, 2021. Laura Roca/Warmi Power/Handout via REUTERS

The Warmi project empowers Indigenous Aymara women in Bolivia's highlands by teaching them taekwondo, so they can defend themselves against domestic violence attacks, often perpetuated by partners or other family members. These Indigenous “cholita” women who live in the high-altitude cities of La Paz and El Alto, train wearing their traditional skirts and bowler hats.

Men are not afraid of hitting women. That's why women live in great fear. I have suffered a lot of physical and psychological abuse since I was a child. Up until now that I am an older woman, I have always suffered a lot - Huayhua, 52-years-old

According to UN Women, eight out of ten Bolivian women suffer some type of violence during their lifetime. This year alone, Bolivian authorities have tallied 48 femicides, mostly by partners or husbands of the victims.

These free workshops have reached 20,000 Bolivian women. Their objective is to provide women with the tools they need to stop certain aggressions.

Our workshops look at psychology, attitude and emotions, to empower women to be able to stop certain aggressions. So women can recognize when they are in a situation of violence, a toxic relationship and can stop violence before it occurs and reaches femicide - Laura Roca, a sports psychologist with Warmi Project

Femicide and gender based violence is evidently a rampant issue in Bolivia. The onus to prevent it should not fall on these women, but the patriarchy should know that they are not going to tolerate abuse and they are willing to take matters into their own hands.

——————————————————————————————————————

Coerced sterilization of Indigenous women is still happening today in Canada according to a report released this week by a Senate committee on human rights. The committee is urging the federal government to further investigate the “heinous” practice by compiling data and creating strategies to end it. The report also says that coerced sterilization affects other marginalized and vulnerable groups, including Black women and other people of colour as well.

Sixteen women shared their experiences of their sterilization for the report. The exact number of Indigenous women subjected to forced or coerced sterilization in Canada is unclear. However, the chair of the Senate committee on human rights, Salma Ataullahjan, says that the prevalence of coerced sterilization is both underreported and underestimated.

A number of Indigenous women who were forced or coerced into sterilization live on reserves in remote areas where hospitals are far away and may even require air travel.

Away from their family and communities to give birth, many Indigenous women experience language and cultural barriers. Many women are not given adequate information or support to understand and to be informed of their rights, including their sexual and reproductive rights - Report

Karen Stote, an assistant professor of women and gender studies at Wilfrid Laurier University, says that even after provincial eugenics laws were repealed, coerced sterilization of Indigenous women continued in federally operated “Indian hospitals,” where about 1,150 Indigenous women were sterilized over a 10-year period up until the early 1970s. The belief that sterilization is done for women’s own good is fueled by racism and paternalism, which still underpin health policy today according to her.

Forced or coerced sterilization is an abhorrent practice that strips women of their autonomy and violates their right to choose what happens to their bodies.The patriarchy and white supremacy think they have a right over women’s bodies, but survivors and advocates have been speaking out about the need for justice and accountability. Given that coerced sterilization is still occurring in Canada, the government must address the issue with urgency.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Seyran Ateş inside Berlin’s Ibn-Rushd-Goethe, the mosque she founded in 2017. Credit: Courtesy of Integral Film

Ateş is part of a new documentary, Seyran Ateş: Sex, Revolution and Islam, directed by Turkish-Norwegian filmmaker Nefise Özkal Lorentzen. The documentary explores Spiritual Islam, which encourages gender equality and inclusivity of LGBTQ2S+ believers, unlike Political Islam. Ateş wants to show how Islam can be compatible with democracy, gender equality and LGBTQ2S+ identities. She hopes to challenge the assumption that Islam is inherently unaccepting of LGBTQ2S+ people.

You just need to look to the history and the theology. In Ottoman times in Turkey and in Andalusian Spain during the time of the scholar Ibn Rushd and the poet Ibn Arabi, homosexuality was accepted and widely practiced. It was always part of our culture - Seyran Ateş

At 21-years-old, Ateş was shot in the neck by extremists while providing counselling at a women’s centre. The horrific event inspired her to embrace the religion and study it more closely. She was also motivated by conversations with family members and Muslim clients who dealt with issues such as forced marriage and honour killings. She opened the Ibn Rushd-Goethe mosque in 2017 where there is no hierarchical or patriarchal structure and everyone prays side by side. She also views the hijab as a tool of oppression.

If the majority of Muslim women in Germany are not veiled, why [is the media] highlighting the minority, and traditions from the seventh and eighth centuries? Perhaps the media isn’t imaginative [or] creative enough to show Muslim women without the headscarf - Seyran Ateş

Ateş is doing important work challenging the view of Islam as a monolith. Too often, LGBTQ2S+ people feel isolated from both queer spaces in addition to Muslim spaces. Ateş is carving the path for people to see how spirituality does not have to be separate from the queer experience.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Soto discusses how he struggled to assimilate both to heteronormative and hypermasculine societal expectations growing up in America. He also had to grapple with sometimes being perceived as “too American” and other times “not Mexican enough.”

…the constant demand I placed on myself to appear to be many things and not others at the same time was overwhelming - Jose Soto

Soto was able to accept himself as “a Mexican living in the U.S. who identified as gay and queer” and come out to his mother and everyone else as a teenager. Since then, he celebrates his multiple identities and being a part of two languages and cultures. He realized that many of his barriers were self-imposed, and he does not need to strictly be a single version of himself.

I celebrate all these things every single day now, allowing all aspects of my identity in a fluidity and consistency that doesn’t impose limits to any of them. I thrive professionally in English while singing along to Spanish songs, writing primarily in English while reading Spanish literature and watching Mexican television shows, all while being as gay and queer as I want to be, not only during Immigrant Heritage Month and Pride Month, but all year long - Jose Soto

Soto’s essay encourages us to reflect on the ways in which dominant society forces us to create confines in our mind about who we can be. He reminds us that it does not need to be that way and we can embrace all parts of ourselves at the same time.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

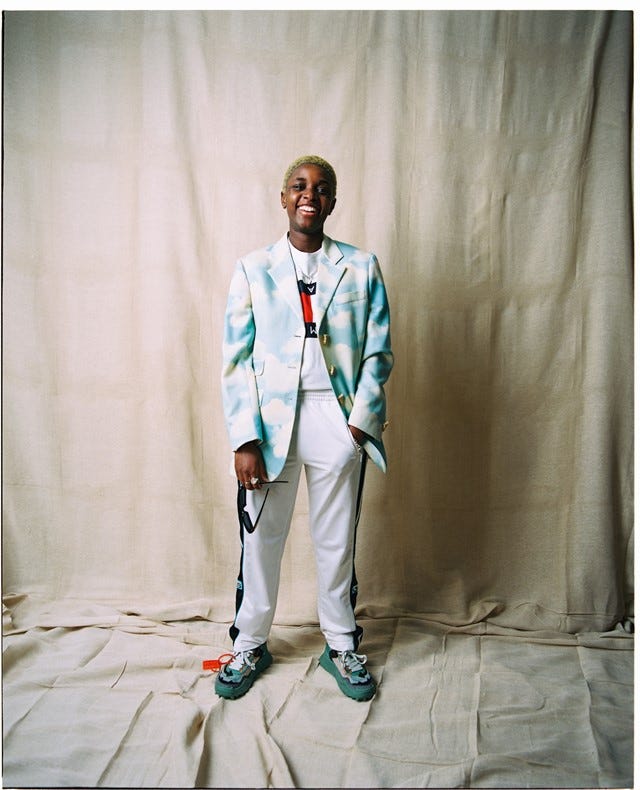

SherellePhotography Isaac Lamb

Sherelle is a Black queer woman in the electronic scene who DJs, co-runs the Hooversound Recordings label and is now starting a new label called Beautiful to address the lack of spaces for Black LGBTQI+ artists in the electronic scene. The label’s debut release is due to be a compilation of tracks from artists “pushing the boundaries of Black electronic music.”

In an interview with DAZED, Sherelle discusses her experience in the male-dominated music industry. Sherelle thinks it is important that there are more spaces owned by queer people that are a safe space for them. The Beautiful clubs will serve as that kind of place where Black queer people can freely take risks and create new genres.

I think that's super important in terms of representation, people like yourself doing the same thing as you and being like, ‘Fuck, I feel really inspired to be in the music scene - Sherelle

Beautiful will be a label putting out up-and-coming artists’ music alongside established artists within the scene, primarily from Europe and the UK. Beautiful will also be hosting educational and technical workshops that go over what to expect in the industry. Sherelle hopes to showcase the diversity of Black electronic music. Ultimately, she wants to create a sustainable community where Black queer artists can thrive.

I want this to be a collaborative effort, especially if people feel they could get involved for the better. I really hope that when people see Beautiful, it will be a place combating the really unfair systems that are against Black communities and especially black LGBTQI+ communities.

Sherelle is using her passion and influence to create new spaces for Black LGBTQI+ communities. It will be exciting to see the art that comes out of the Beautiful label and all the young people it will inspire.

—————————————————————————————————————- Samiha Hossain (she/her) is a student at the University of Ottawa. She has experience working with survivors of sexual violence in her community, as well as conducting research on gender-based violence. A lot of her time is spent learning about and critically engaging with intersectional feminism, transformative justice and disability justice.

Samiha firmly believes in the power of connecting with people and listening to their stories to create solidarity and heal as a community. She refuses to let anyone thwart her imagination when it comes to envisioning a radically different future full of care webs, nurturance and collective liberation.