Global Roundup: Kashmiri Dais Revolutionizing Childbirth, LGBTQ+ Families in the Midwest Documentary, Delhi Queer Art Exhibition, Nakuru GBV Activist, Malawi Sex Worker Case

Curated by FG Contributor Inaara Merani

(Feminism in India)

Hajrah Begum is a 70-year-old Dai, who is affectionately known as the “Dai of Amargarh”, and has provided services as a midwife for 50 years. Hajrah only completed up to her tenth grade of school and she has remained steadfast in her commitment to supporting the people of her community. Hajrah says she never received any formal midwifery training; she learned the art from her mother and grandmother, a tradition passed down through generations. Due to her years of experience and knowledge, Hajrah has a strong sense of intuition – she can discern a woman’s pregnancy just by touching their hand.

During the last stage of my mother’s life, she implored me to make a solemn promise: to carry forth the tradition of aiding in childbirth, a legacy that has been passed down through generations. As her final wish, she entrusted me with the responsibility to ensure that this invaluable tradition endures, urging me to pass the torch on to the next generation. – Hajrah Begum

In addition to promoting natural childbirth through her practices, Hajrah also actively educates women in her community about the benefits and empowerment that come when individuals embrace the natural process of childbirth. And Hajrah provides her services for free, which ensures that no pregnant woman is left without the support and guidance that is needed during pregnancy.

Another Dai in Sopore, Kashmir is 64-year-old Magle, who also learned the art by attending deliveries with her mother. Since she was a young girl, Magle has been an integral part of the community. After getting married at a young age and after her husband passed away early, Magle had to learn how to sustain herself and her family. During the lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic when hospitals were overwhelmed with patients, she continued her work in remote areas where medical facilities were scarce.

Both Hajrah and Magle stand as beacons of hope in their respective communities. their selflessness and sense of care for others is evident through their ongoing commitment to supporting pregnant women, despite their age or circumstances.

Instead of a conventional clinical relationship, there is a desire for a more personal connection–a friendship. Women seek someone they can trust and rely on, turning the pregnancy experience into a shared journey marked by understanding, support, and a bond that goes beyond traditional healthcare roles. – Dr Zulfkar Nabi, medical officer at Sopore Hospital

David Miller/Hulu. (Them)

A new documentary, We Live Here: The Midwest, explores what it means to be LGBTQ+ in communities where they may be bullied or shunned. The film introduces five queer and trans families in Iowa, Ohio, Nebraska, Minnesota, and Kansas. Melinda Maerker, director and producer, says she chose to focus on the Midwest because it is commonly known as “the heartland of family values”.

We thought that the term ‘family values’ has been co-opted by the right. But what does it really mean? In many ways, it’s a good term that means help your neighbor, it means be kind. But why does that term exclude certain families, certain peoples within the queer community? So how can you say we represent family values if we’re exclusive? Melinda Maerker.

The five families that this documentary follows includes: Nia and Katie from Ohio, a queer, trans couple with five children who are searching for a new community after getting expelled from their church; Mario and Monte Foreman-Powell, a gay Black couple living in Nebraska with their infant daughter; Denise and Courtney Skeeba, lesbian farmers in Kansas who had to begin homeschooling their son after he was bullied in school; Debb and Jeff Richmond, a trans couple in Minnesota; and Russell Exlos-Raber, a gay teacher fighting for LGBTQ+ rights for students in Ohio alongside his partner Adam.

There are talks for the production of a second We Live Here film centred in the American South, however it has not yet been confirmed. We Live Here is challenging the mainstream portrayals of queer and trans communities in film by showcasing the realities of what it means to be LGBTQ+ in spaces where you are not welcome, and how this can impact oneself, as well as one’s family.

Featured Image Source: Abir Pothi. (Feminism in India)

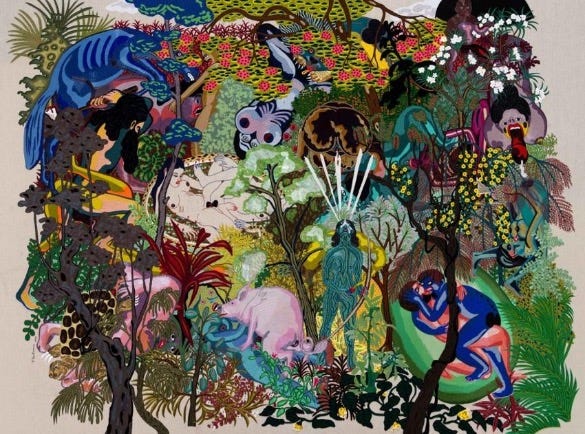

The exhibition was on display at the India Habitat Centre in Delhi, India and was curated by the human rights organization Engendered, with support from the University of California’s Feminist Studies Department. Vichitra Desh represented a large group of minorities with both shared and different experiences in a hierarchical society. In addition to works by Indian artists, other countries within the Global South were represented, including from Iran, Brazil, Pakistan, Mauritius, Argentina, and South Africa.

Drawing on popular culture, epic myth, histories of orientalist, discourse around climate change, and debates around the role of religion in the modern world, the artwork showcased the artists’ daily lived experiences that are often sidelined by the societies in which they live. Artists explain that the Indian government, and Indian society, often try to discipline sexualities that do not fit the norm; Vichitra Desh demonstrated how nuanced versions of love, including marriage, have a complicated relationship with religion but should still have a place within society.

Heteronormativity often dominates the art world, leaving only a small space for queer art and expression, and this is the case particularly in India. There is a new, fresh wave of queer art which moves beyond just sexuality and focuses on taboo issues such as family, faith, and society. Vichitra Desh also highlighted how language has become an effective tool in the emancipation of post-colonial societies, and queer societies in particular. Looking past the “quest” for marriage equality that the queer experience is often defined by, the exhibition promoted awareness and sensitization and moved beyond the strict boundaries that tend to limit queerness.

The point is to look at the liberation of terminologies. Queer has the potential of expanding its meaning from its normative pedagogical references and to re-contextualise it from an intersectional and marginal point-of-view. – Myna Mukherjee, curator of Vichitra Desh

Kismet, 2022, Pencil and hand, embroidery on linen, 87.5 x 116 in. (Feminism in India)

Ms Fidelis Wambui Karanja the CEO of Young African Women Initiatives (right) monitors women taking a tailoring course at a centre in Bondeni, Nakuru County.

Karanja’s work extends throughout the slums of Free Area, Bondeni, and Kaptembwa in Nakuru, Kenya, as well as throughout the city. Her work does not differentiate; she supports low-income women, as well as women across socio-economic groups, including professionals who rarely talk about GBV in their homes. When speaking about her work, the activist compares her daily experiences to that of a driver who is trying to remain in contact with the road. Karanja says the driver must steer properly and apply the brakes properly to ensure the shock absorbers work. In the case of her work, the “shock absorbers” have helped to keep women and girls safe.

Being a shock absorber of women and girls in slums and posh areas who suffer daily violence means you absorb the impact of abuses, disagreements, pain, torture, tears, and tension. My greatest joy is when I reduce the tension in the life of a girl or woman by showing her the right way to fight GBV at home, work place or any other place. – Fidelis Wambui Karanja

Karanja says she is always ready to absorb the blow that comes with her work – the negativity, stress, anxiety, and other emotions – in order to lessen the impact it has on victims of GBV. Growing up, Karanja was frequently exposed to GBV and vowed to champion the rights of girls and women when she grew up.

Due to the nature of her work, she also has experienced threats to her safety and livelihood, many times from husbands of the women she has helped as they fear they will be exposed through legal proceedings. Yet, Karanja continues to face challenges with legal authorities as patriarchal systems still dominate. But despite all the hurdles and setbacks, the Nakuru activist has made great progress and has educated dozens of women across the area, promoting the right to live freely, and not in fear of discrimination or violence.

I have never felt like I want to quit. I feel great when people get justice. Barriers to justice are concentrated in the corridors of justice. It is annoying to see an officer demanding a birth certificate to prove that a 13-year-old girl was raped by a 50-year-old man. Sexual misconduct, assault, child abuse and related crimes do not require a birth certificate for proof. – Fidelis Wambui Karanja

South African human rights activists protest at Home Affairs Offices, against homosexuals imprisoned in Malawi, under Malawi's anti-gay laws, which date from the colonial era, May 20, 2010, Cape Town. | Nardus Engelbrecht/Gallo Images/Getty Images. (Open Democracy)

In December 2021, 29-year-old trans woman Jana Gonani was imprisoned and is currently serving an eight-year sentence at the Chichiri men’s prison in Blantyre City, Malawi. She was charged under two counts of “false pretence” for presenting as a woman, as well as one count of “unnatural offence”. The crimes that Gonani was charged under both come from the country’s colonial era of penal law.

With the help of Nyasa Rainbow Alliance (NRA), a Malawian LGBTIQ organization, Gonani was able to file an appeal in the High Court in February 2022. She challenged the constitutionality of Section 153 of the law pertaining to “unnatural offences” which was the British colonial legal term for homosexual sex, or sodomy. At the time of her arrest, Gonani was also charged with the offence of obtaining goods under “false pretence” after one of her clients reportedly accused the sex worker of falsely representing herself as a woman.

Gonani’s appeal to Section 153 marks the first time in history that Malawi’s “unnatural offence” law has been legally challenged on its constitutionality. However, unlike other African countries in the region such as Ghana, Uganda and Kenya, the Malawian parliament has not yet made efforts to introduce anti-gay legislation.

Also earlier this year, the High Court merged Gonani’s petition with another petitioner, William Akster, a Dutch national who was charged with nine counts of sexual abuse against youths, mostly young men. The High Court decided to combine their cases because the two issues were the same, however grouping Gonani in with a sexual predator is demonstrative of the lack of awareness and understanding about trans experiences, especially trans sex workers.

Despite the ongoing setbacks and the backlash from far-right protesters, activists in Malawi are hopeful about the outcome of the case, which may take anywhere between a few to several months.

I am a human being just like anyone else. It hurts me to hear that religious leaders and other faith groups seem to be against people like me. I know I’m not the only trans woman in Malawi or the world, hence I want justice to be done in my case and [for other] people like me. – Jana Gonani

Inaara Merani (she/her) recently completed her Masters degree at the University of Western Ontario, studying Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies with a specialization in Transitional Justice. In the upcoming years, she hopes to attend law school, focusing her career in human rights law.

Inaara is deeply passionate about dismantling patriarchal institutions to ensure women and other marginalized populations have safe and equal access to their rights. She believes in the power of knowledge and learning from others, and hopes to continue to learn from others throughout her career.