Global Roundup: Kenya & Honduras Women Protest Femicide, Japan Queer & Femme Collective, Two-Spirit Artists & Men Bead, Book on Misogyny and Islamophobia

Curated by FG Contributor Samiha Hossain

Thousands protest against increasing violence against women in Kenya as they march to the parliamentary building and supreme court in the capital Nairobi [Gerald Anderson/Anadolu Agency]

Thousands of people gathered to protest in cities and towns in Kenya against the recent slayings of more than a dozen women. The anti-femicide demonstration on Saturday was the largest event ever held in the country against sexual and gender-based violence.

In Nairobi, protesters wore t-shirts printed with the names of women who were killed this month. The crowd, composed mostly of women, brought traffic to a standstill. “Stop killing us!” the demonstrators shouted as they waved signs with messages such as “There is no justification to kill women.” The crowd in Nairobi was hostile to attempts by the parliamentary representative for women, Esther Passaris, to address them. Accusing Passaris of remaining silent during the latest wave of killings, protesters shouted her down with chants of “Where were you?” and “Go home!”

Kenyan media outlets have reported the slayings of at least 14 women since the start of the year, according to Patricia Andago, a data journalist at media and research firm Odipo Dev who also took part in the march. Odipo Dev reported this week that news accounts showed at least 500 women were killed in acts of femicide from January 2016 to December 2023. Many more cases go unreported, Andago said. Furthermore, a 2022 survey found at least one in three Kenyan women had endured physical violence at some point in their lives.

I am here because I'm angry. It is wrong, we are tired and we want something to be done about it. - Winnie Chelagat, 33

Campaigners want the authorities to expedite justice for all recent victims of sexual and gender-based violence. Dozens of local rights groups say the government must declare femicide a national emergency and class femicide as a specific crime, distinct from murder. Victim-blaming has been rife on social media, however, with commenters in Kenya's so-called "manosphere" blaming murdered women for their own deaths. Despite Kenya having robust laws against gender-based violence, most perpetrators go unpunished. When prosecutions are brought, they often drag on for years in court.

(Photo by Orlando SIERRA / AFP)

Dressed in black as a sign of mourning, about 300 women marched last Thursday in Tegucigalpa to the National Congress, on Honduran Women’s Day, to protest the increase in femicides. The police placed barriers around Congress as a new legislative period began with the attendance of President Xiomara Castro, but the protesters managed to jump over them and reached the lower part of the building.

We are marching today against all violence, from domestic violence to femicide. We demand the approval of the Comprehensive Law against Violence that the president promised; we can’t wait. -Sandra Deras, activist

According to the Women’s Rights Center, violence against women is on the rise in Honduras. In the first 15 days of 2024, at least 16 women were murdered. And according to the National Autonomous University of Honduras’ Violence Observatory, 380 femicides were registered in 2023, compared to 308 in 2022. Congress established January 25 as Honduran Women’s Day because on that date in 1955, women were granted the right to vote and participate in the country’s political life.

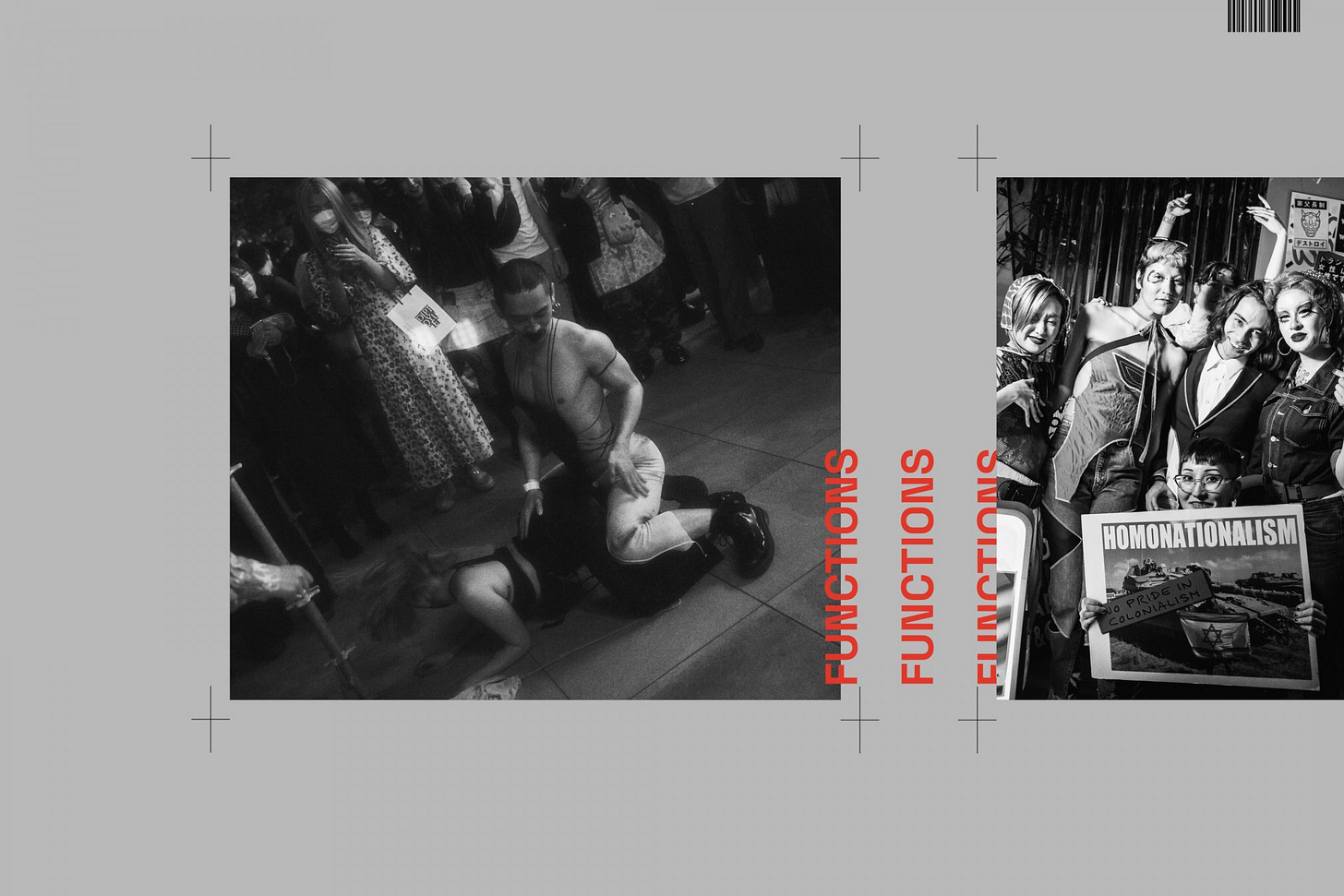

Founded as a response against discrimination, queer and femme collective WAIFU is bridging the gap between music and politics in Japan, pioneering a focus on inclusivity, accessibility and activism in the club scene and beyond. The seminal queer and femme collective released the Japanese capital’s LGBTQI+ scene from the shackles of Ni-chōme (Tokyo's gay district) back in 2019 and hasn’t looked back. It’s known for open-minded, inclusive parties that can encompass anything from zine fairs and drag queens to bondage and hard techno.

WAIFU began as a response to an incident which happened in Ni-chome, when member Elin was denied entry to a lesbian party for being a trans woman. Being turned away led the people present to form their own “counter-party,” held just 10 days later. A novel idea in Tokyo at the time, the “counter-party” designed an anti-harassment policy, sold zines promoting activism, and had a chill out space. Since its inaugural event, the collective has booked many well-known DJs, hosted talks and a radio show and inspired many local partygoers to launch their own inclusive events. Mixmag spoke to three of its members: Elin McCready, Maiko Asami and Midori Morita, who shared the thinking behind the collective.

WAIFU doesn’t have a door policy that excludes people. Elin says they ask people to agree to a statement of values at the door and no one so far has refused to follow those guidelines. However, the organizers realised that they couldn’t rely on the club’s staff to respond to instances of sexual harassment so they got clubbers who agreed with the policy to help. Clubbers willing to help wear a “SECURITY” sticker. The club also has posters with QR codes where clubbers can anonymously report sexual harassment.

A lot of people didn’t feel comfortable in either existing club spaces, because they were excessively cisheteronormative and also frequently had a lot of harassment, and some because there just weren’t spaces for queer people (though there were for cis gay people, particularly men). I remember someone coming up to me at one of the early parties and thanking me for having started the space, literally in tears. It is really amazing to feel that the thing you are doing turns out to be something that’s so genuinely needed. -Elin McCready

Because it can be hard to talk in clubs and sometimes sharing things through social media can become complicated, the organizers host talks and workshops that enable them to relay a message and have an open dialogue in real time. The organizers have experienced people approaching them and expressing their appreciation for the political work that WAIFU does. Organizers hope that even for people who just come to dance, the collective’s activism will encourage them to engage in activism themselves.

Thomas Benjoe, who lives in Regina, has been beading since he was nine years old. He beads regalia for his wife and children to wear at powwows. (Submitted by Thomas Benjoe)

A growing number of Indigenous men and two-spirit artists have been picking up the craft of beading.

Thomas Benjoe learned to bead when he was nine years old. Now he uses those skills to show appreciation for his wife. Throughout history, women have predominantly been beaders, with those skills passed down through the female line in families. But Benjoe said that doesn’t mean men weren’t beading; they were sometimes just not as open about it.

It’s not really a male or female thing; it’s just an appreciation for the way that we’ve adorned ourselves for thousands of years. -Thomas Benjoe

Benjoe, who hails from Muscowpetung Saulteaux Nation, remembers when he first started beading. He became curious watching his aunt work on powwow regalia, so she invited him to help her fill in some of the beadwork. He caught on quickly. From there, he developed his own style of beadwork and played around with designs while still respecting tradition. Benjoe said it was important for him to understand that this art form isn’t just a matter of stitching beads to leather – there is meaning behind the work. His aunt passed down teachings from her great-grandmother about the significance of the beadwork.

Jordy Ironstar is proud of his Carry the Kettle Nakoda Nation background, which he presents in much of his work. (Louise BigEagle/CBC)

Jordy Ironstar travels around the world as an Indigenous community advocate. As a child, Ironstar would admire powwow regalia, and his love of beadwork grew. Finally, in 2019, he took the opportunity to learn beading from his cousin. He created a medicine wheel keychain. She told him he was a natural. He adopted a traditional style inspired by the powwow trail, using designs, colours and quillwork that honor his ancestors. But he often makes more contemporary pieces as well, to help reflect the stories or issues he wants to convey through his creations. Ironstar recently hosted an earring-making workshop open to all genders.

When we see beauty, we associate beauty with femininity. So a lot of people have this perception that if a man is to make beautiful earrings, then they’re not manly. -Jordy Ironstar

A new book from journalist Nadeine Asbali sheds light on what it’s like to live as a visibly Muslim woman in Britain today. Veiled Threat is part memoir, part political essay, detailing the hardships of growing up as a hijabi and how these struggles are interlinked to Britain’s systematic disempowering of its Muslim citizens. Over the course of the book, Asbali discusses topics such as the online Muslim alt-right (or “akh-right”, as she puts it), white feminism and its saviour complex, the representation of Muslim women on screen and why Muslim women deserve control over their voices. Dazed spoke to Asbali to discuss her inspirations, thoughts on the current state of Muslim representation in film and TV, and her hopes for the future.

Asbali says the process of writing Veiled Threat was cathartic for her and helped her process trauma. She says the book is mostly formed from her personal experiences. She starts each chapter with an anecdote and then relates it to a wider systematic impact Islamophobia has had on visible Muslim women.

In the introduction, I state that Veiled Threat wasn’t written to tick off your book club’s diversity quota. My goal was to give at least one visibly Muslim woman a voice when we’re so often spoken over. Still, I know that, unfortunately, for the average white liberal reader, that won’t be enough. -Nadeine Asbali

Asbali also discusses the ongoing genocide in Gaza and how Muslim women are being policed on their attendance at protests. She mentions the dangers of depoliticising Islam and the fight for independence in Algeria in the 1950s and 60s, as an example. It is difficult for Asbali to continue living her normal life while Gaza is being decimated.

I have Muslim students who clearly want to discuss what’s going on, but we’re not allowed to talk about it, which must be so disorienting for them. Seeing the general British population and government so unmoved by what’s happened versus the care that was had with the Ukraine crisis feels like a confirmation that Islamophobia is still so deeply rooted in this country. -Nadeine Asbali

Asbali says having a book like hers as a teenager would’ve been life-changing for her and would’ve made her feel less alone – she hopes she can give that to young readers today.

Samiha Hossain (she/her) is an aspiring urban planner studying at Toronto Metropolitan University. Throughout the years, she has worked in nonprofits with survivors of sexual violence and youth. Samiha firmly believes in the power of connecting with people and listening to their stories to create solidarity and heal as a community. She loves learning about the diverse forms of feminist resistance around the world.