Global Roundup: MENA Women Vs Male Guardianship Policies, Spain LGBT Rights Threat, Africa LGBTQ+ Activists, Indigenous Drag Queen & Gender-Affirming Care, Queer Debut Memoir

Curated by FG Contributor Samiha Hossain

A woman on the street in Amman, Jordan, one of the countries in the region where women’s freedoms remain restricted. Photograph: Artur Widak/Getty Images

Aya (not her real name) is nearly 30, but she is forbidden from leaving her home in Amman, Jordan. She can’t go for lunch with her friends and has no legal right to decide where to live, work or study.

I am a prisoner at home. If I go out without my family’s knowledge, they’ll lock me in my room and beat me so hard that I’ll feel pain for months. I’m threatened with death. There are so many girls like me. -Aya

While most governments in the region say they allow women to obtain passports and travel abroad without requiring guardian permission, legislation regarding married women offers sanctions if they do so. Human Rights Watch (HRW) has published a new report on male guardianship policies in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Rothna Begum, a senior researcher at HRW, notes that restrictions on movement is a form of violence against women.

You have a spectrum of women who are controlled; some have a curfew, but other women can’t even see their friends at a cafe. You have no ability to have a social life in that respect. Women talk about their lack of agency contributing to depression; some feel so controlled they attempt suicide. -Rothna Begum

Lina (not her real name), 24, works remotely from her home in Amman because her father won’t allow her to leave the house. Although she makes more money than anyone in her family, she doesn’t know how to spend it since she can’t go out. Recently, Lina turned down a job promotion because she didn’t feel qualified, as she says she doesn’t have good social skills because of her inability to go out and socialize like her brothers.

People will try to tell you this doesn’t exist in Jordan. They’ll say: Look at all the women out in public, living normal lives. But you can’t see all the women inside. -Lina

Members of Chrysallis (Association of Transgender Children and Youth Families) take part in a Gay Parade in Barcelona, Spain, July 15, 2023. REUTERS/ Albert Gea

Spain's leftist government passed pioneering legislation in February allowing transgender people aged 14 and over to change their legal gender without the need for psychological or other medical evaluation and judicial approval. Children aged 12 to 14 can change their gender with parental consent and judicial approval.

Ana Valenzuela, who has a trans 12-year-old daughter, said her daughter had asked to change her gender on the national ID card as soon as possible, fearing a PP-Vox government would do away with her right to self-identify. Valenzuela said "it's very sad that children are conscious of this." She advised the government during the drafting of the "Trans Law."

Vox has vowed to repeal the Trans Law and has joined the PP in challenging it before the Constitutional Court, arguing it violates child protection rights and the right to bodily integrity.

It has also called for excluding hormone replacement therapies from the public healthcare system so that only paying customers of private providers have access to gender transition procedures, as well as banning trans women from women's sports and bathrooms.

Polls point to the PP winning the most votes in Sunday's election, but landing shy of an outright majority and likely needing Vox to be able to form a government. Olga Nadal, vice-president of trans youth rights group Chrysallis Catalunya, said the community could not afford to see the law repealed.

Photos via Teen Vogue

Throughout the continent of Africa, queer youth are tirelessly fighting back against anti-LGBTQ+ policies that threaten their own community, with the latest movement taking place in Uganda. In May, President Yoweri Museveni signed an anti-gay bill into law, and it has been described as one of the world's most "brutal anti-LGBTQ laws." Beyond Uganda, countries like Nigeria, Cameroon, Ghana, and Kenya are some of the 32 countries in the region with harsh and inhumane laws governing and targeting LGBTQ+ people. Teen Vogue spoke to 5 LGBTQ+ activists on their work fighting for change – 3 of them will be highlighted in this roundup.

Bandy Kiki grew up among a local tribe called Nso in the Northwest Region of Cameroon, a country where LGBTQ+ people have been criminalized since 1972.

There weren't any queer representations around me growing up, and it made me feel alone; I was convinced I was going to hell when I connected my feelings to the anti-homosexual teachings in the Bible. -Bandy Kiki

Feeling unsafe in her community, Kiki emigrated to the U.K. and, from there, vocally advocated for queer rights at home. Through entrepreneurship, advocating through Rainbow Migration (a platform helping LGBTQI+ people to seek asylum and immigration), and taking the role of Living Free UK Director, Kiki remains at the forefront of reshaping and prioritizing the lives of vulnerable groups.

Alex Kofi Donkor is the Director of LGBT+ Rights Ghana, a safe place for the Ghanaian community. Kofi Donkor had to navigate their identity while growing up in a predominantly religious Christian home, where they were told being queer was a sin. In June, as a continuous way of celebrating Pride Month, Kofi Donkor's platform rolled out the annual "Colour Dialogue," a series of virtual conversations focused on LGBTQ+ activists and allies.

Queer activism for me is about imagining the vision of wanting to achieve a society where everyone is free and celebrated while exuding their very best. -Alex Kofi Donkor

Brilliant Kodie, a queer activist living in Maun, Botswana, created Setabane, a modern-day, independent, youthful, and fresh queer storytelling platform. The activist has collaborated with late African Portraiture Wenzile Dube. To further elevate the vision of Setabane, the platform-turned-online magazine is currently in the final stage of registering as an NGO in Botswana while also expanding and building projects in the rural parts of Botswana.

Photo Courtesy Oliver McDonald

The Scarlette Ibis, also known as Oliver McDonald is transmasc, two-spirit and Cree from Peguis First Nation in Treaty 1—all of which shape his drag and advocacy. McDonald is a member of the University of British Columbia's Trans Coalition, a new group campaigning to add gender-affirming care to UBC’s student health-care plan. The coalition formed because the Canadian university’s student health-care plan did not include trans health care. Paying out of pocket for hormones, surgery, and other treatments was a staggering burden for many trans students already struggling under the rising costs of living.

In April this year, the coalition succeeded: UBC will now insure trans health care. Drag performers—both in and out of makeup—were a vital force for advocacy and queer joy during a tense campaign.

I hope that with this win it lets other activist groups … see that it is possible. -Oliver McDonald

UBC’s gender-affirming care campaign represents just one facet of a bigger fight for trans rights occurring across the continent. Trans health care in Canada is notoriously underfunded and inaccessible, and transphobic discrimination is on the rise. Last year, protestors harassed over 15 drag queen story hours across Canada.

McDonald plans to do more performances that represent his Cree culture. He emphasizes that his drag career builds off of the Indigenous and two-spirit drag performers who came before him and created a thriving scene in Vancouver. He hopes to pay it forward through organizing drag events to platform other Indigenous drag performers, with the principle of ensuring that all get paid equitably for their work.

Performing is really fun and I love it, but the more important thing is [to make sure] that other Indigenous people can show their stuff. -Oliver McDonald

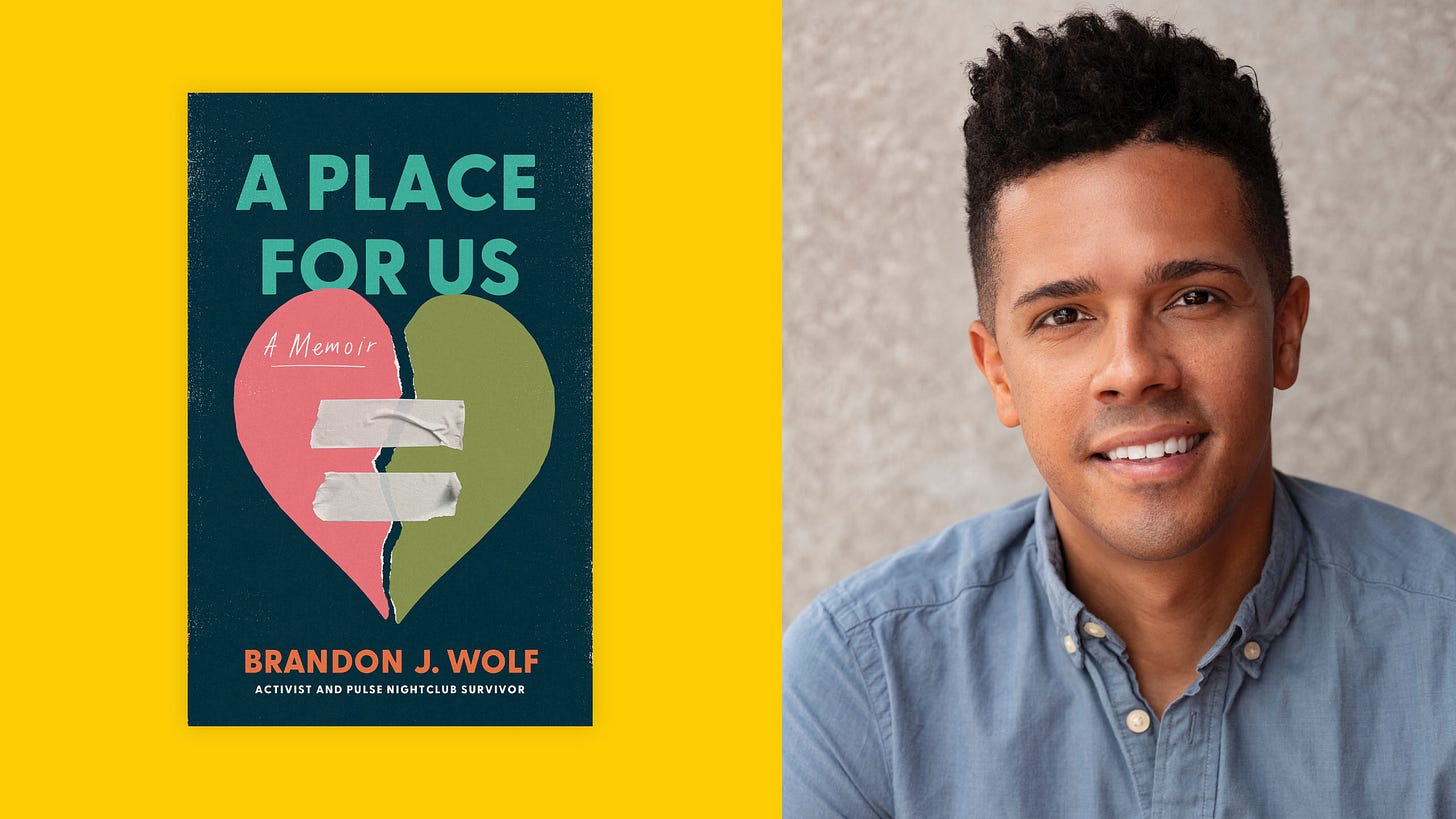

Credit: Book cover courtesy of Amazon Publishing; Author photo by Sean Black; Elham Numan/Xtra

Brandon Wolf is a survivor of the Pulse nightclub shooting in 2016 and in his new debut memoir, A Place for Us: A Memoir, Wolf takes us on a journey—recounting his childhood, his search for a community after leaving Oregon, the grief of losing his chosen family and the impacts of gun violence. Now the press secretary for the LGBTQ2S+ advocacy group Equality Florida, Wolf’s vulnerable storytelling acknowledges the depths of his sorrow while also sharing a message of hope and optimism.

Wolf discusses how his best friend Drew, who died in the shooting, was one of the first people to teach him about unconditional love.

So much of our [community’s] complicated relationship with love is about self-loathing; it’s about internalized homophobia and hate that we have. Drew unapologetically loving me, flaws and all, challenged me to learn to love myself in the same way. -Brandon Wolf

Wolf starts the book with the story of his mom’s death from cancer when he was 11 years old. He calls his mom the first ally he ever had in his life. Wolf has very visceral memories of both his mom’s death and the Pulse nightclub shooting, including the scents and sounds.

I also wanted to tie the way that death imprints itself on your mind to stories of loss around Pulse. One of the themes I wanted people to take away was that all of these moments leave scars, and there’s no way you can erase them. You just learn to grow around them. -Brandon Wolf

Wolf shares the guilt he struggles with about being the one who asked Drew and his boyfriend Juan (who also died in the shooting) to come to Pulse with him that night. He was unsure whether to be so vulnerable in his book, as he feared right-wing people could use it as a weapon against him. Ultimately, he felt it was an important aspect to include. Over the last seven years, Wolf’s purpose has been to “relentlessly, unapologetically, unashamedly advocate for a world” that Drew and other queer people would be proud of.

Samiha Hossain (she/her) is a student at the University of Ottawa. She has experience working with survivors of sexual violence in her community, as well as conducting research on gender-based violence. A lot of her time is spent learning about and critically engaging with intersectional feminism, transformative justice and disability justice.

Samiha firmly believes in the power of connecting with people and listening to their stories to create solidarity and heal as a community. She refuses to let anyone thwart her imagination when it comes to envisioning a radically different future full of care webs, nurturance and collective liberation.