Global Roundup: Myanmar Women Online Abuse, Spain Feminists vs Far-Right Party, Intersex People & Reparations, India Women Hip-Hop Group, Queer Muslim Memoir

Curated by FG Contributor Samiha Hossain

A female police officer who fled Myanmar after the military coup in 2021 checks a mobile phone at an undisclosed location in India on the border with Myanmar [File: Anupam Nath/AP] via Al Jazeera

Women who have expressed views on social media opposing military rule in Myanmar are being subjected to abuse, including calls for their arrest and threats of violence, rape and death by pro-military online users, a study has found. Myanmar Witness led the study, Digital Battlegrounds: Politically Motivated Abuse Of Myanmar Women Online, and said that social media platforms such as Telegram and Facebook were not doing enough to tackle online abuse or were not responding quickly enough to requests to remove abusive users and content.

Politically motivated abuse against women from and in Myanmar increased at least fivefold in the aftermath of the military’s seizure of power in February 2021, according to the study, and the prevalence of abusive posts targeting women was 500 times higher on Telegram compared with other international social media companies.

Online abuse and doxxing attacks are having a silencing effect and causing women to retreat from public life…Survivors report attacks on their views, person and dignity, and threats of rape, death and violence with severe emotional and psychological impacts. -Digital Battlegrounds: Politically Motivated Abuse Of Myanmar Women Online

Doxxing was the main form of abuse found in the study. The women subjected to doxing appeared to have been singled out for having commented positively on groups in Myanmar that oppose military rule. Women were also subjected to sexualised disinformation campaigns where pro-military social media users depicted their targets as “morally corrupt”, “racially impure”, “promiscuous” and “sexual prey.”

The report’s authors said social media platforms need to be more accountable, should work with women’s rights organisations in Myanmar and devote more resources to monitoring the local language content they host. Social media companies also need to improve their response times when abuse and threats are reported and must quickly remove abusive accounts when threatening activity is flagged, the Myanmar Witness said.

Ángeles Leal, a volunteer with Women Survivors, cooks aubergines with white sauce and peppers for the association's twice-weekly hot lunch. November 16 2022 | Elena Ledda via openDemocracy

The Casa Grande community centre in the Pumarejo neighbourhood of Seville in Spain is home to around 20 groups, including Women Survivors of Gender Violence (Mujeres Supervivientes de Violencias de Género). The group offers support and training to women survivors of violence, and most of its members are migrant women.

Women Survivors is one of 78 organisations working to eradicate gender violence in Andalucía, Spain’s most populous region, whose public funding was cut off overnight in 2019. The Women’s Institute of Andalucía (IAM), part of the regional government, cut funding to about 240 feminist groups.

The far-right Vox party took 12 seats in Andalucía in 2018 – the first time it had achieved electoral success in a regional parliament – giving it the power to exact concessions from other parties. Like many far-right groups, Vox has ultra-conservative attitudes towards women, is obsessed with traditional notions of ‘family’ and opposes abortion. The party has consistently spoken against the concept of gender violence, arguing that “violence has no gender or labels”.

Women Survivors has survived thanks to local neighbourhood support and the work of volunteers, but other women’s groups have closed or cut back their operations. For example, in a seaside town near Cadiz, Learn to Live (Aprende a Vivir), an organisation combating drug dependency, had to close its shelter, which provided free housing to women undergoing detox.

Some women had to go home, some to public outpatient facilities, and some ended up on the street. -Ángeles Moreno, Learn to Live President

For Seville’s Women Survivors, there are other consequences of the rise of the far right in Andalucía including the normalization of hateful rhetoric.

[Racism was] already in the streets, but it didn’t have a party giving it a voice in Parliament. Now that it does, hate speech is accommodated within public institutions. -Sandra Heredia, Roma activist and councillor for the left-wing Adelante Andalucia party in Seville

According to Julia Espinosa, a University of Seville sociology professor specialising in gender equality and the radical populist right, the distance between grassroots feminist groups and public institutions is key in explaining the lack of a united response to Vox in the region. She says that most feminism is taking place in the streets and not involved in mainstream politics. Still, for many activists, the response to the extreme right lies in their daily work.

We resist through spaces like this – we support each other when complaints are lodged, evictions are made, or whatever. -Silvia Talavera, 22-year-old volunteer with Women Survivors

NURPHOTO/GETTY IMAGES via Teen Vogue

Researcher and activist Courtney Skaggs argues for intersex harm reparations in an op-ed for Teen Vogue. Skaggs shares how the decision was made for them rather than them being given the choice of having a non-essential surgery when they were of age to consent. They were “feminized by force,” which they say is not a unique experience.

Almost 2% of the world’s population experiences variations in sex characteristics (VSC). These differences can manifest in hormone production and regulation, internal and external sex organs, and chromosomes. People who experience VSCs sometimes identify with the term and community known as “intersex.” The UN has called medically unnecessary surgeries that intersex people cannot consent to human rights violations, yet many doctors continue to perform such surgeries.

State legislators are attempting to codify the erasure of intersex bodies while denying life-saving care to trans youth as well. According to Human Rights Watch and interACT, in 2022 legislative sessions, 22 states had a pending or proposed bill that would “purport to authorize intersex surgery.” Three more states, Arizona, Arkansas, and Alabama have passed such bills. Skaggs says that legislative sessions in 2023 could see more attacks on intersex bodies.

Since 1996, intersex activists have been calling for the medical harm to stop. The demands have been clear: Intersex youth deserve the opportunity to participate meaningfully in care decisions; medically unnecessary surgeries on children must end. -Courtney Skaggs

According to a study, A national study on the physical and mental health of intersex adults in the U.S, more than 43% of intersex participants rated their physical health as fair/poor and 53% reported fair/poor mental health. Many respondents reported being diagnosed with depression), anxiety, or PTSD. Intersex activists call for reparations in response to such devastating harm and outcomes. Skaggs says that reparations can include public apologies, public investigations of harm, paying intersex people for their activism and education, employing intersex people to provide care and work in affirming clinics, donating to intersex organizations, making space for intersex people to lead medical care reform and research, or providing low cost or free intersex affirming care. At the very least consent should come first they say.

We want to be whole, autonomous beings who are encouraged to blossom. We demand respect for bodily autonomy and dignity from lawmakers, caregivers, and community members. Intersex rights are human rights and we call for reparations…-Courtney Skaggs

Wild Wild Women, from Mumbai, have released three singles and performed around the country despite being dismissed by music industry figures and not having a record deal via The Guardian

The eight members of the Wild Wild Women collective have had to deal with knockbacks from the men who dominate the music industry and press. They have had to cajole and fight their parents for permission to play and travel to gigs – once they have convinced them that hip-hop is suitable for women to perform. And they have to juggle full-time jobs with their music.

We wanted to speak up, as women in a country where women have been kept down and forced to be silent. -Pratika Prabhune

One of the songs members Pratika Prabhune and Ashwini Hiremath wrote is called Raja Beta (King Son), which mocks the way Indian men like to be coddled and pampered by their mothers. The mockery is accompanied by chants in an uptempo chorus of “Don’t give injustice a chance” and “Who are you to stop me?”

While they have made some headway convincing their families of their musical ambitions, the group’s main challenge now is to claim some space in the Indian hip-hop and rap scene, which has only a small number of female rappers. Without a record deal, the group pool their money to record their music. So far, they have released three singles and have performed in several cities. The band also has to tread carefully in the minefield that Indian society has become under the Hindu nationalist government – any imagined slight to Indian culture or tradition could cause offence.

The band sings in Hindi, Marathi, Tamil and Kannada as well as English, flipping between languages in each song. They plan to experiment with Indian instruments to give their music an even more distinctive sound. The main goal of Wild Wild Women, though, is to get the voices of Indian women heard.

By putting our own voices out there, we are representing the larger audience of women too. -Pratika Prabhune

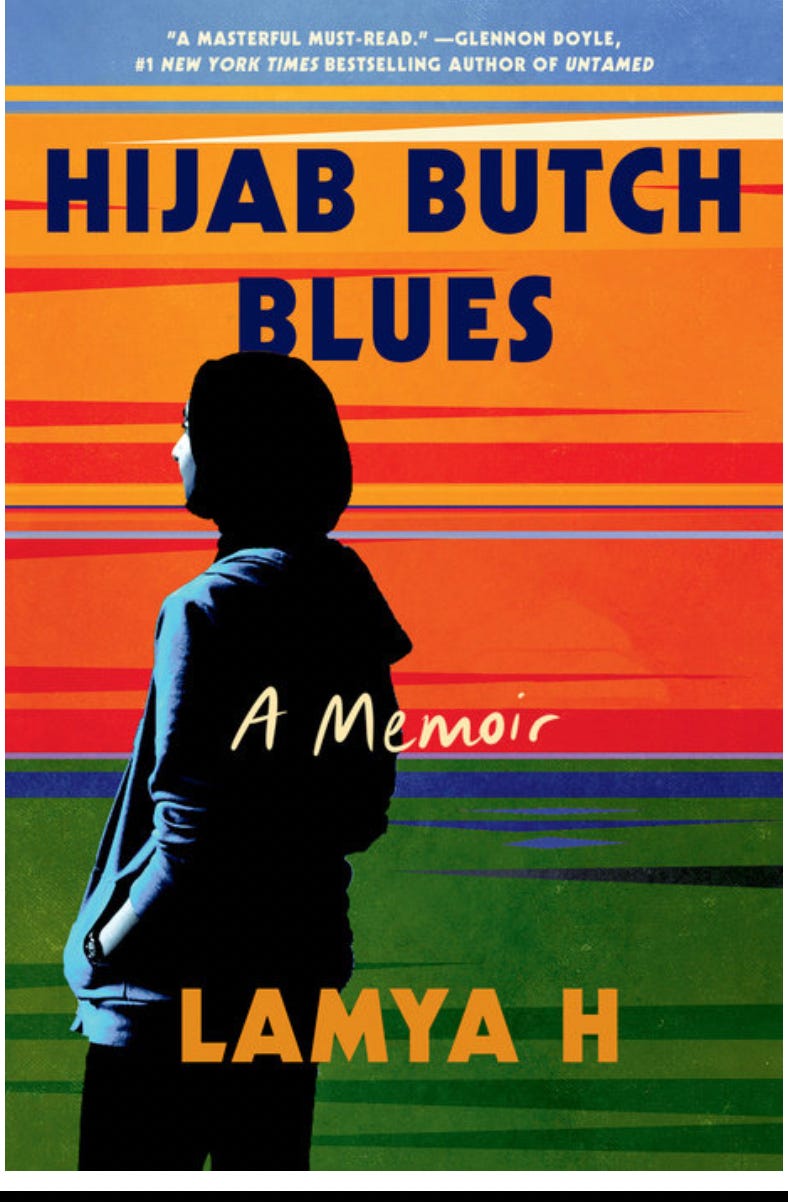

Hijab Butch Blues is a memoir by Lamya H. coming out next month. It is about how a queer hijabi Muslim immigrant survives her coming-of-age by drawing strength and hope from stories in the Quran. The memoir spans Lamya’s childhood to her arrival in the United States for college through early-adult life in New York City. Gal-dem published an extract from Hijab Butch Blues, where Lamya recalls a tense trip to the doctor’s office.

Lamya begins with how there are only a few certified doctors in the city that do the kind of medical examination she needs for her immigration forms. The exam suddenly becomes increasingly invasive and uncomfortable with questions about mental health, drug use, STIs, and asking the doctor to assess whether or not she’ll engage in “harmful behavior.”

That I even need a medical examination for my immigration forms is terrifying. That my ability to stay in this country is dependent on a special doctor who can sign and seal and swear to tell the truth is terrifying – as if the decades of student visas, years of employment authorizations that expire every twelve months, years of visa stamps that must be renewed when I leave the country – as if all of this hasn’t been terrifying enough. - Lamya H.

To Lamya’s surprise, the doctor is Arab like her and seems “kind and sweet” – an “aunty doctor,” as she calls her. Lamya feels at home but is quickly met with invasive questions and advice as is often the norm with aunties.

When asked if she needs to order a pregnancy test, Layma says “I’m definitely not pregnant,” and when probed by the aunty doctor, Layma owns her queerness for the first time.

I hesitate. Even now, a decade after I came out, a decade spent building a queer life, I hesitate. I hadn’t anticipated this aunty doctor, hadn’t anticipated my careless answer, and I don’t have a game plan for navigating this immigration situation in which I legally have to tell the truth in response to this question that will out me. -Lamya H.

Samiha Hossain (she/her) is a student at the University of Ottawa. She has experience working with survivors of sexual violence in her community, as well as conducting research on gender-based violence. A lot of her time is spent learning about and critically engaging with intersectional feminism, transformative justice and disability justice.

Samiha firmly believes in the power of connecting with people and listening to their stories to create solidarity and heal as a community. She refuses to let anyone thwart her imagination when it comes to envisioning a radically different future full of care webs, nurturance and collective liberation.