Global Roundup: Sierra Leone New Maternity Unit, Queer Irish Counter-Protest, Pakistan Feminist and LGBTQ+ Art, Ethiopian Writer on Physical Touch, Indigenous Author Completes Trilogy

Curated by FG Contributor Samiha Hossain

Photograph: Topia Salone/The Guardian

In Kono District, in the Eastern Province of Sierra Leone, where diamond-rich earth was once exploited to fund a decade-long civil war, a new legacy is being built in its capital, Koidu, where a 60% women construction team is building the Maternal Center of Excellence. Most of the women are working in construction for the first time and are conscious they are helping to build the region’s future. The building will serve the Koidu government hospital next door, and promises a change for the region and country, which in 2019 had one of the highest rates globally for maternal mortality with a healthcare system blighted by civil war and Ebola, which killed 7% of its healthcare workers.

It is for us, the women who will give birth here. That’s why we are putting in effort to build the hospital. That is why you see plenty of women here. -Hawa Baryoh, 21

Baryoh was earning five to 10 leones a day (20 pence to 40 pence) selling corn on the street. Now, as the breadwinner for her family, she is helping to train other women on the site. Baryoh says she hopes the project will give other women courage to work there, too.

Isata Dumbuya, the director of reproductive, maternal, neonatal and adolescent health at Partners in Health Sierra Leone, was born in Kono, but has spent a large part of her life in the UK where she trained in the NHS as a midwife. She returned about five years ago and has set her sights on improving the region’s maternal healthcare. Dumbuya says part of her work has been changing mindsets so that death in childbirth is not accepted as normal.

You keep on seeing the results, even the little things. That keeps you going, and every year when you hear the reduction in maternal mortality rates you think, collectively, if we keep on going, we can make this happen. -Isata Dumbuya

The goals for the new centre include a five-fold increase in family-planning visits, as well as a reduction in the rate of facility-based maternal deaths to less than 1%, and stillbirths to less than 2%. Dumbuya highlights the importance of the new maternity centre as a training ground, with the possibility of developing exchange programmes with other hospitals abroad.

Photo CorkBeo

Queer Irish people and allies formed a human chain to protect a library from an anti-LGBTQ book protest taking place on the street outside. Cork City Library has been the focus of right-wing anger for months, with people harassing library staff in an attempt to get LGBTQ+ books removed from its shelves.

On Saturday, about 300 people turned out in support of the library and its staff, and in opposition to the Ireland Says No rally, which was organised by conservative groups. During the course of the counter demonstration, groups of people, including from Cork Says No To Racism and Cork Rebels For Peace, waved Pride flags, held signs and sang songs.

Two women, who said they were members of the Irish Writers Union, said they were part of the counter-protest because the issue of library attacks is affecting the rest of the country.

We travelled down because this is not just affecting Cork, there have been attacks like this on libraries across Ireland and it’s important to take a stand, support the workers who are being targeted and support the right of libraries to have the right to choose the books they want to have. -Unamed woman

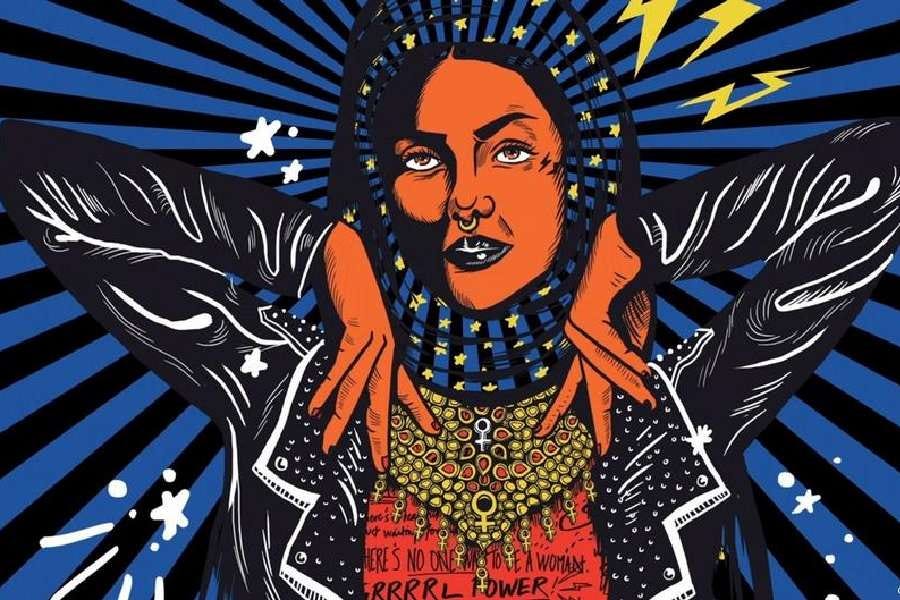

Shehzil Malik

The Pakistan Art Forum, established in 2014, supports emerging artists dealing with feminist or LGBTQ themes, allowing unconventional voices to emerge. It first used social media and digital platforms to feature more eclectic and inclusive artists and styles. After the pandemic, the forum also set up a physical address that serves as a safe space for artists, allowing them to push boundaries and start a dialogue about queer and LGBTQ identity politics, sexuality and power, all while challenging patriarchy — themes that are taboo in Pakistan.

Throughout the ages, art has been a medium of reform, resistance, used to highlight various social dilemmas. It is important for us to not only curate shows that are aesthetically appealing, but also to use art as a medium to shed light on various issues. -Imtisal Zafar, founder of PAF

Zainab Aziz is a young emerging artist showing feminine strength by focusing on the mundane. Aziz works primarily with oil paints and has a signature style featuring a monochromatic palette and large voids in her representations. Through black-and-white contrasts, she aims to highlight social hypocrisy.

My work revolves around female protagonists, the way they share their secrets and bond. I consider the female body as a landscape of a society which bears multiple stories within it. -Zainab Aziz

Aziz laments the lack of connections for young and emerging artists to break through. She points out that the Pakistan Art Forum is the only platform in the country that supports emerging and young talents. According to Aziz, PAF's unique proposition is that they help relatively new artists sell their work immediately by encouraging, supporting and guiding them to showcase their work in galleries and helping them get media exposure.

Ahmer Farooq boldly tackles LGBTQ issues in his art, shedding light on how gay people are pressured into forced heterosexual marriages to uphold a façade of "normalcy." He explains that a gallery refused to show his work under his concept, which described how the art deals with gay forced marriages. He says that the press also often refuses to share his art and cover his shows, fearing backlash or legal consequences, as even openly discussing homosexuality can get one into trouble. Farooq is grateful that PAF has never censored his art, showcasing his work without prejudice or modifying his concept. He feels safe spaces are essential to many people's survival, as marginalized people need a "bubble to be themselves."

Melek Zertal/For The Times

Mihret Sibhat, the author of The History of a Difficult Child, writes an article about how in moving to the United States of America she lost a culture that embraced physical touch.

Sibhat describes how it was common in Ethiopia for people to have “intense friendships” where physical touch was normal.

I knew adult women who bragged about how they slept with their best friends: holding each other tightly, face to face. As teenagers, my friends and I used to kiss each other’s faces and necks repeatedly. During sleepovers, we hugged with the sort of passion we felt in our bones, in our hearts. -Mihret Sibha

When she moved to California at 17, Sibhat recounts how she put her arm around her sister, like they did in Ethiopia, and her sister told her to take her hand off because people will think they’re lesbians.

My sister’s words announced the loss of platonic hugs and touches that were so integral to my well-being, my survival. Years later, I would learn that I am indeed a lesbian, so any part of me that was aware of this at the time must have shrunk out of fear. -Mihret Sibha

Sibhat discusses the loneliness she felt in the U.S. When she visited Ethiopia in 2018 after 17 years in the U.S, she noticed a drastic drop in hand-holding, touching and hugging between friends on the streets. She links this to the anti-gay hysteria in Ethiopia over the last decade and a half, mostly spearheaded by a nongovernmental organization with funding from American evangelicals.

There is irony when a culture that rejects homosexuality because it is seen as Western turns around and throws out friendship traditions because of Western definitions. It is also ironic that the only way to recover the lost shades of friendship is to fully embrace the queerness within all of us, and the queerness that can exist in platonic relationships. -Mihret Sibha

Photo: (Warren Kay/CBC

Indigenous author Katherena Vermette released her debut work of fiction, The Break, in 2016 and its follow-up, The Strangers, in 2021. Set mostly but not entirely in Winnipeg's North End, the two books weave together a story about multiple generations of Métis families. The saga, which unspools from an act of violence committed in the snowy wastes of a Manitoba Hydro corridor, comes to a potential conclusion with the release this week of The Circle, the third chapter in what is now a trilogy. Vermette says she was surprised seven years ago that anyone would "let her" write a novel.

While there is no shortage of stark material in the first two books of the series — these stories are ultimately about resilience in the face of enormous harm — Vermette said she was striving for more of a balance with the third.

I was articulating this book as, 'I want to write about trauma without it being traumatic.’ I'm really interested in trauma. I'm interested in the way that we experience it sometimes in multiple layers throughout our lives. I'm interested in how we hold it in our bodies and how we show it to the world. I think that drives a lot of our motivations and why people act the way they do is based on things that have happened to them. -Katherena Vermette

Vermette acknowledges some readers don't want to enter it, as easy as her prose is to follow, because of the heavy topics covered. However, she wants people like her to feel seen.

When people in my communities or people who look like me feel seen and feel that I somehow rendered an authentic version of something that might be familiar to them, that's always my favourite compliment. -Katherena Vermette

Samiha Hossain (she/her) is an aspiring urban planner studying at Toronto Metropolitan University. Throughout the years, she has worked in nonprofits with survivors of sexual violence and youth. Samiha firmly believes in the power of connecting with people and listening to their stories to create solidarity and heal as a community. She loves learning about the diverse forms of feminist resistance around the world.