Global Roundup: Thailand LGBTQ Activist, Canada Trans March, Nepal Asexual Community, Nonbinary Muslim Author, South Africa Queer Visual Artist

Curated by FG Contributor Samiha Hossain

Image Courtesy: Anticha Sangchai

Anticha Sangchai is an LGBTQ activist, a professor, a mother and bisexual. Sangchai talked to Thai PBS World about the underlying challenges for LGBTQ people in Thai society, which eventually pushed her into advocacy for gender diversity. It all began over 10 years ago, when she realised that she’s bisexual.

When I was trying to understand who I really am, I realised that I needed a friend, a community, or simply knowing how these people live their lives or what they are doing, so that I could understand myself and how I can continue with my life. That was when I realised what I can do more for society. -Anticha Sangchai

Sangchai’s first step into advocacy was volunteering for LGBTQ organisations. This eventually developed her into an activist for gender diversity, especially in the deep south. Although Thailand’s southernmost provinces are dominated by Muslim communities, which strongly oppose same-sex marriage, Sangchai said that people in those areas are as gender diverse as in Bangkok, and other cities that have large LGBTQ communities. Despite that, LGBTQ people in the deep south are still subject to marginalisation and mistreatment.

The activist discussed the challenges she faced coming out to her family and how she believes the gender bias in Thai culture is mostly rooted in the patriarchy. Among the negative stereotypes that Anticha encountered was that bisexuals are all promiscuous.

The significant part of the patriarchy is having power over others and there are standards of what is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, which often says that one gender is right more than the other. This persists in every circle of society, whether it’s politics, education, religion or families, which is intense. -Anticha Sangchai

Sangchai feels that the marriage equality bill in Thailand only approves marriage between LGBTQ couples, but does not ensure the right to establish their own families or legally recognise them as parents. Nonetheless, she has witnessed significant changes in Thai society over the past decade, for which she credits the many senior LGBTQ activists who fought for their fundamental rights, back when gender equality was barely discussed in the mass media. Today, Sangchai is a professor as well as a “spiritual counsellor” and “energy healer” to help her students. She urges people to listen to their heart and be kind to themselves.

Hundreds marched from the Manitoba Legislature to The Forks on Saturday in support of trans visibility and equal rights. (Travis Golby/CBC)

In Canada, transgender people and allies took to downtown Winnipeg streets in the hundreds on Saturday, showcasing visibility and solidarity at a time when trans rights are under attack in parts of North America. The march, now in its sixth year, is held as part of the 2024 Pride Winnipeg Festival and dovetails with this year's theme of "Transcend Together," said Pride Winnipeg's executive director, Sean Irvine.

Right now there's a lot of challenge for the trans community — they're being pushed back. So it's great that we're advocating, moving forward and really trying to push that community and their message forward for equal rights. -Sean Irvine

In the province of Alberta, proposed new policies affecting student gender identity, youth gender-affirming surgeries and health care, and trans women's participation in sports have come under fire. And in the province of Saskatchewan, the provincial government last fall introduced a Parents' Bill of Rights. It requires parental consent for children under 16 who want to change their names or pronouns at school. The law is currently being challenged in court after the government used the notwithstanding clause in Canada's charter of rights to enact it. The clause allows government to override certain fundamental rights, reviewable every five years.

Emily Turner spoke highly of having a safe space for transgender people to be out in the community and feel proud of who they are. The outward show of public support "kind of fills the heart with a bit of joy," said Turner. For Laura Jones and Violet McAuley, the atmosphere of kindness was notable, as was the opportunity to show support. They have a relative who is trans, they said. Greysen Gauthier lauded Pride Winnipeg's approach of having the trans march take place a day before the annual Pride parade.

Nepali Aspecs members meet for their first offline event in Kathmandu, holding an asexual flag to mark International Asexuality Day in 2022.

Nepal has been touted as a beacon for queer rights in Asia and is among the few countries granting sexual minorities equal protection in the constitution. Last year, the country’s top court issued an interim order allowing queer individuals to register their nuptials in government offices until a marriage equality law is passed.

Manita Newa Khadgi felt mixed emotions upon seeing a video on asexuality on YouTube in 2020 – joy, validation and a curiosity to connect with others who identified as asexual. Seeking to find a community, Khadgi turned to Instagram, anonymously opening an account called Nepali Aspecs. Aspecs is an umbrella term referring to those on the asexuality and aromantic spectra. Four years on, Khadgi has not only expanded the online community but has become the face advocating for the visibility of asexual and aromantic people.

I was 29 when I found the term asexual. I lost the queer joy and security of knowing oneself. It would have made a huge difference in my life had I known earlier, and I just wanted for others to have that. -Manita Newa Khadgi

Khadgi accuses many queer rights advocates of tokenising the asexual community only when discussing intersectionality and inclusivity. They says aphobia is prevalent mostly in the queer community because asexual and aromantic people “decentre romance and sex” that is seen as a key part of queer culture. They say that asexual people in the country feel erased.

The messages Khadgi initially received on Instagram showed a lack of understanding about asexuality in absence of wider visibility. They said people not knowing about the label made them “pathologise themselves, feeling alienated and dehumanised.” The community has helped several people questioning their sexual orientation or seeking acceptance.

When you go to other queer groups, it feels you’re going to a certain camp and need to fit in – you feel like an outsider. I never felt that [at Nepali Aspecs]. -Brownie, 23

On Instagram, Nepali Aspecs aims to provide accurate information on asexuality and aromanticism, along with different identities within the spectra, which is largely missing in Nepal and elsewhere. Ahead of Pride month in June, the community was hosting pre-Pride hang-outs, a series of events and interaction programmes to assert their place in the queer movement and become visible to more people on the asexual and aromantic spectrum who might be in search of a community.

I created this group out of compulsion because I was desperate to find another Nepali asexual person. But every time a new person comes to us now, it feels magical. Just four years ago, I thought asexual people did not even exist in Nepal and if I were the only one. Now we have a community. -Manita Newa Khadgi

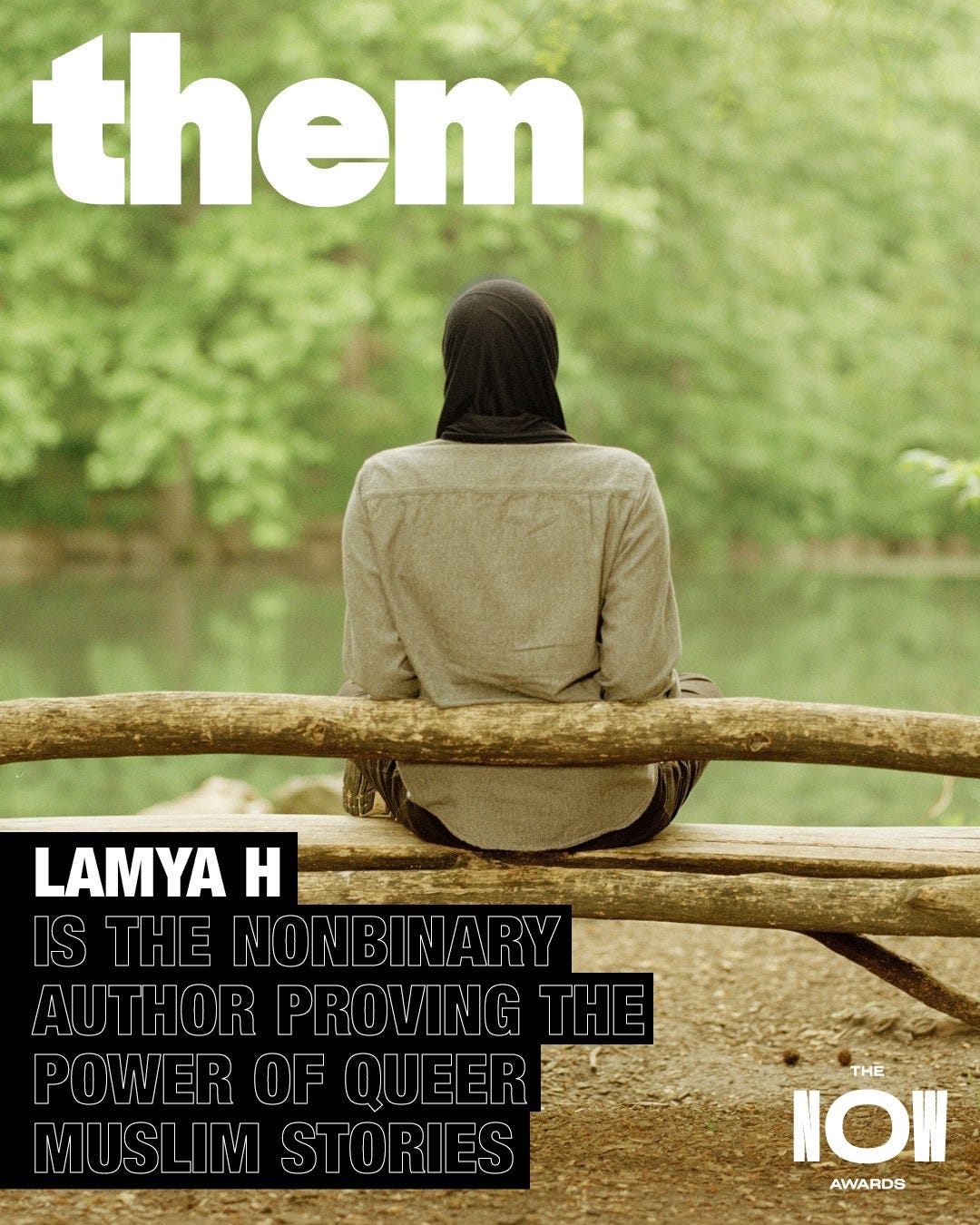

Photo: Ramie Ahmed

With their acclaimed debut memoir Hijab Butch Blues, Lamya H demonstrates that queer and Muslim narratives are inseparable. Hijab Butch Blues grapples with the narrator’s relationship to the Quran, and their desire to see their queer coming-of-age challenges reflected by characters in the holy text. Lamya’s memoir weaves Quranic stories with their own personal narrative of growing up in a predominantly Muslim country, realizing they’re gay, and immigrating to the U.S., all while keeping their identity hidden from their family.

The memoir took hold immediately after its early 2023 release and has since won a series of prestigious literary prizes, including the Stonewall Book Award, the Brooklyn Public Library Book prize, and the Israel Fishman Nonfiction Award. Earlier this year, it was named a Lambda Literary Award finalist. Zaina Arafat, Palestinian-American writer and the author of You Exist Too Much, interviewed Lamya for Them.

I’ve found myself repeatedly coming up against the tragedy of queerness. -Lamya H

Lamya discusses publishing under a pseudonym and how it allows them to be honest and vulnerable in their work without feeling too exposed – but it also makes it more difficult for them to gauge readers’ reaction to their work. Still, they’ve received DMs on Instagram and Twitter from readers telling them how much the book has meant to them. They also recently did their first virtual event, where they could actually see live reactions, which they described as “strange” and “cool.” As a Palestinian, Arafat relates to Lamya’s “calculus of hiding and not hiding.”

On the one hand, we as Palestinians are desperately trying to make our voices heard and our lives seen, asserting our existence in an effort to resist erasure. On the other, we’re witnessing ourselves splashed across the media, against our will, in our most vulnerable and dehumanized states. For Lamya, so much of the gulf between these two states is signified by the hijab itself. The visibility of their Muslimness can lend invisibility to their queerness. -Zaina Arafat

Lamya’s next literary project will be a work of fiction that tells a story of a friendship set in a place where movement is constrained. They’re also focusing on helping their toddler avoid some of the challenges that they encountered growing up.

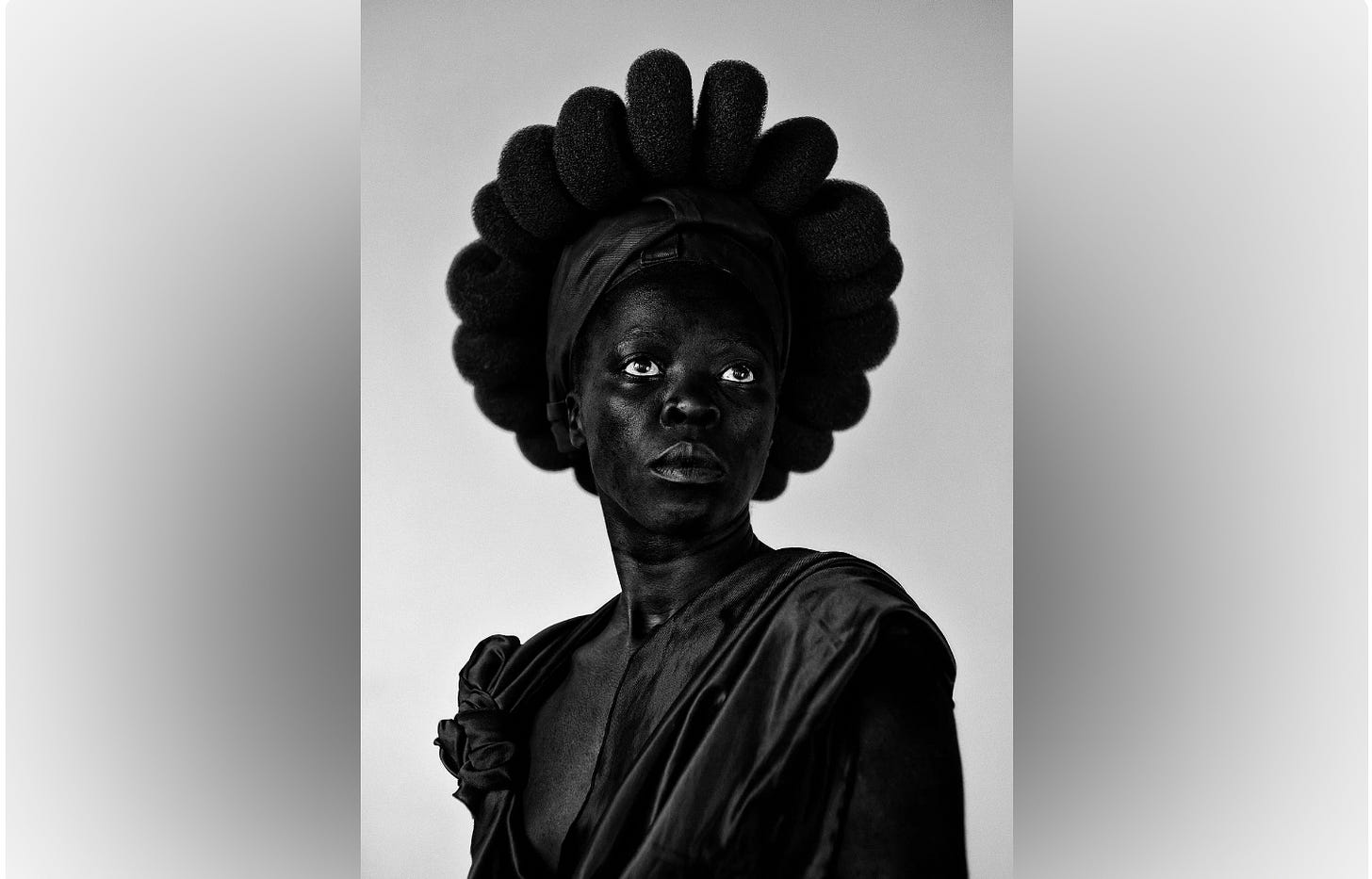

(Zanele Muholi)

South African artist Zanele Muholi's new exhibition features more than 260 photographs from the past three decades. Describing themself as a visual activist, Muholi documents and celebrates queer communities who often don’t see themselves reflected in society, with a particular focus on South Africa’s Black LGBTQIA+ culture.

Muholi discusses how they want people to learn the importance of community from their exhibition. They note that other groups have archives so it is important for queer people to have their own archive as well.

I want people to walk into the [Tate Modern exhibition], look at the images and think, “Wow, I see me in these photographs”, even if those people don’t live in the same country, there’s something that connects them. -Zanele Muholi

Muholi lives in South Africa and says that one’s experience growing up in the country differs based on whether they lived in towns or in the suburbs. They say that even with the constitution, some people will never come out in their lifetime. As someone who is nonbinary, Muholi does not always feel safe but also notes that “safety is an issue for everyone, everywhere in the world.”

What makes Muholi proud is that they can express themself. They use the term “participant” over “subject” because they see the person being photographed as more important than the photographer. They ask participants to look directly at the camera as “a way of talking back.”

Because as Black people, we were never in the position where we were able to talk back. But [it’s] also to give people strength. It’s about resilience. Talking back, looking back, eye contact is such a powerful stance. -Zanele Muholi

Samiha Hossain (she/her) is an aspiring urban planner studying at Toronto Metropolitan University. Throughout the years, she has worked in nonprofits with survivors of sexual violence and youth. Samiha firmly believes in the power of connecting with people and listening to their stories to create solidarity and heal as a community. She loves learning about the diverse forms of feminist resistance around the world.