Global Roundup: Trans Men Face Barriers Accessing Abortions, Seoul Pride Parade, Mexico Sex Worker Journalists, Africa & Middle East LGBTQ Activists, Indian Women Anthology

Curated by FG contributor Samiha Hossain

Volunteer Alex Cascio wears pins as she gathers signatures for a proposed abortion amendment at Ferndale Pride in Ferndale, Michigan, U.S., June 4, 2022. REUTERS/Emily Elconin

Getting an abortion after being raped as a teenager drove trans man Adri Perez to help set up an LGBTQ-inclusive fund in the U.S. state of Texas to support others wanting to end their pregnancies. For Perez, co-founder of the Texas-based West Fund –which has paused its operations following the June 24 Supreme Court reversal Roe v Wade – the fight for trans rights and abortion access have much in common.

Trans justice and reproductive justice are linked together by the fact that what they are both fighting for at their core is bodily autonomy. -Adri Perez

Cazembe Murphy Jackson, a 42-year-old trans man, has spoken out about his own experience of pregnancy and abortion as a result of a rape in college, in an effort to improve services. He said the mental health impacts of getting an abortion or being forced to carry a pregnancy to term are magnified for trans men and can be deadly, as the changes to their body can increase stress over the mismatch with their gender identity.

Trans people in the U.S. are disproportionately likely to be poor, according to a 2019 study by the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law, and about a third live in southern states, many of which have very restrictive abortion policies. Many of those in work may be unable to seek support and financial aid from their employer as they have not disclosed the fact they are trans and fear discrimination. Some American trans and non-binary people attempt home abortions for reasons including a lack of health insurance, legal restrictions, denials of care or mistreatment, and cost, according to a 2021 study in the BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health journal.

All over the world, gendered language has blocked access to abortion for some trans men. Such barriers lead to people trying to induce home abortions with methods including being kicked, or taking pills bought online according to Clara Rita Padilla, a lawyer and the director of women's rights organisation EnGendeRights. It is vital to centre the voices and needs of trans men in the fight for abortion rights.

DRAG QUEENS DANCE ON A TRUCK LEADING THE PRIDE PARADE IN SEOUL. PHOTO: KANGHYUK LEE via VICE

South Korea’s largest annual queer festival returned to the streets after three years in Seoul last Saturday. It took place this month due to the delay in getting government approval in time for June. According to Seoul Queer Culture Festival (SQCF) organizers, some 135,000 participants attended the main events. The slogan this year was “Live On, Stand Together, Go Onward.” People dressed in all colors of the rainbow, holding flags and balloons that said “Live Love Liberate.”

Everywhere, you can see different colors. I hope you don’t forget that we’re working together to create a world where you can live as you are. -Yang Sun-woo, head of the SQCF

VICE spoke with some people at the festival and asked them what they loved about the event and their message to the LGBTQ community.

I’m still in the closet, like many others, but I’m here today to say: ‘I’m the queerest, at least today. I’m alive. I’m asking for laws for me.’ The pandemic has been hard for all of us, so I hope we try to understand one another more. -Summer

Many of the participants mentioned the anti-gay protesters who were also present, which led to fear and and tension. Shin Seung-ho, 19, decided to make a statement by wearing a hanbok – usually worn by hate groups.

You can see I dyed my hair a crazy color—I’m already noticeable, but I wanted more, so I wore a hanbok. It’s usually what hate groups wear. That motivated me to choose this, thinking a queer person in a hanbok would be more visually striking. I hope that discrimination ends and that the anti-discrimination law passes. -Shin Seung-ho

Participants also expressed their joy at the large turnout and finally having the event after three years. They also said that it is one of the few opportunities they can be their true selves and freely celebrate with their community.

Paloma Paz applies cosmetics before going to work on the streets of Mexico City CLAUDIO CRUZ AFP via France24

In addition to being a sex worker on Mexico’s streets, Paloma Paz, a 28-year-old trans woman, also uses journalism to decry injustices. She began writing articles after seeing fellow sex workers thrown onto the street when the hotels where they lived and worked closed due to the pandemic.

[Journalism] is a way of shouting at society, at the authorities, about what's happening to us…It's not a hobby. -Paloma Paz

Paz and 10 other women write for a free monthly magazine called Noticalle published by the non-governmental organization Brigada Callejera (Street Brigade). Around 1,000 copies of the magazine are printed each month, made of three letter-size sheets of paper folded in half and stapled together. On the cover there is a cartoon of two sex workers with the word Noticalle in the background. The letter O is represented by a condom.

It's a means of communication mainly produced by sex workers for sex workers, who felt misrepresented by the mass media. -Elvira Madrid, founder of Brigada Callejera

Members of the magazine's team distribute copies each month by hand to sex workers in Mexico City. They call this community journalism. Paz says it helps them find out what is happening in other areas where colleagues are. In its June issue, the magazine reported that sex workers had lost up to 70 percent of their income due to the pandemic. Other topics included extortion by organized crime and the case of an indigenous transgender sex worker sentenced to 14 years in prison after she was "unjustly" convicted of murdering her partner.

Krisna, a 51-year-old trans sex worker, was trained at another journalism workshop and now sometimes reports for the digital media Disinformemonos. Using her new skills, Krisna also co-edited a book of interviews by sex workers of colleagues involved in journalism. She says reporting helps her with her self-esteem.

[Journalism] has given me a sharper vision of the news. I have the ability to analyze texts, to see the social and political situation in the world. -Krisna

Haneen Maikey via al Qaws

An article in LGBTQ Nation highlights activists in the Middle East and Africa –some of the most LGBTQ hostile countries– who are at the forefront of civil rights battles in their nations. These activists often do not get much mainstream recognition in the Western world, yet they have been doing the hard work to lift up the queer community. I will share a few of these activists here.

Marylize Biubwa was forced to overcome homelessness after coming out to her family. Biubwa helped lead protests against sections of Kenya’s penal code that outlawed homosexual relations. Her compatriot, Denis Nzioka, has been actively fighting and protecting Kenya’s LGBTQ community since 2009 when he opened up the country’s first underground safe place for sexual minorities and followed that up by publishing Identity Kenya, a magazine for the queer populace, and also edited an anthology of LGBTQ stories from Kenya entitled My Way, Your Way, or the Rights Way.

Born under apartheid, Ishtar Lakhani, has a Muslim mother and Hindu father. While focused on “smashing the capitalist patriarchy,” Lakhani has helmed a variety of programs including the “Sex Education and Advocacy Working Group.” Her efforts fighting on behalf of minorities, led her to be named by the BBC as one of their most influential women in 2019.

Palestinian Haneen Maikey’s voice echoes against racism, colonialism, and pinkwashing. In 2001, Maikey founded alQaws for Sexual and Gender Diversity in Palestinian Society as a part of the Jerusalem Open House, a Jerusalem-based community center. In 2007, alQaws dissociated itself from the Jerusalem Open House and began an independent – and more political – journey. alQaws – meaning “Rainbow” in Arabic – offers peer support to LGBTQ individuals and works to organize queer people in four main areas: the West Bank, the East Jerusalem, Haifa, and Jaffa.

For Maikey, the cause of LGBTQ rights is not dissociated from the rights of Palestinians. She believes that Israel’s LGBTQ rights discourse is “cynically deployed [by the Israeli government] to divert attention from the occupation of Palestinian lands and the daily violation of Palestinian rights.”

I know that there is no pink door through Israel’s illegal, racist wall that welcomes queer Palestinians while oppressing others. -Haneen Maikey

As the LGBTQ landscape rapidly changes across Africa and the Middle East, new leaders continue to emerge. However, these older activists have paved the way and will undoubtedly play a role in guiding their work.

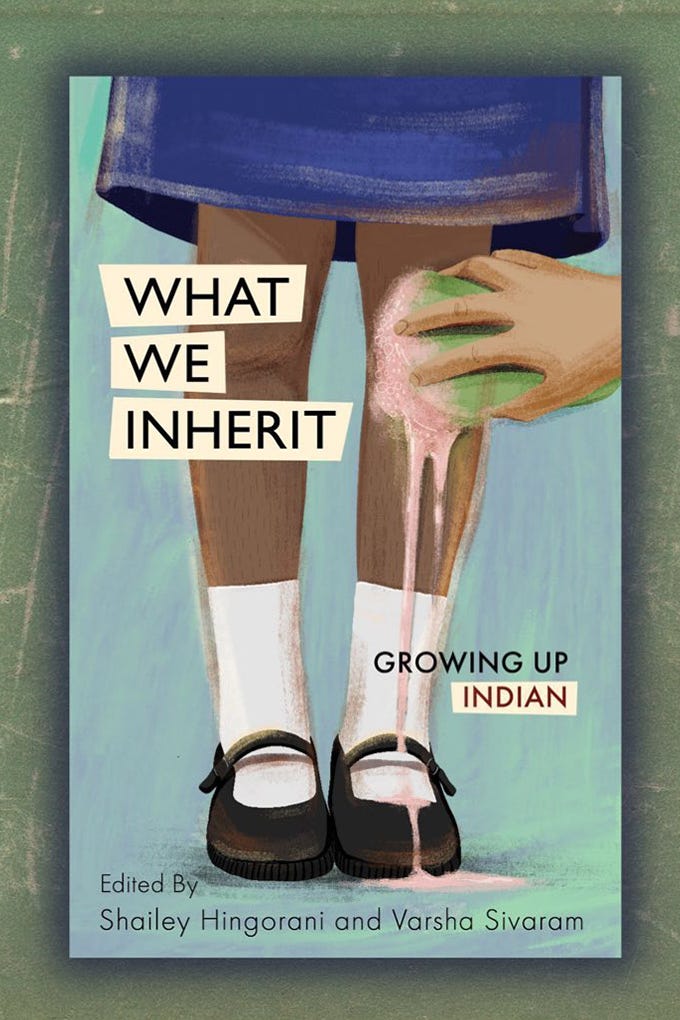

The cover art for What We Inherit is designed by Prashanti Aswani via Vogue Singapore

Vogue speaks to co-editor Shailey Hingorani, Head of Advocacy and Research at Aware, to learn about What We Inherit: Growing Up Indian, an anthology composed of 38 personal essays by Indian women (and a few men) in Singapore and published by women’s rights organization Aware. The anthology tries to capture the “nuanced ways gender and heritage come together to shape our lives.”

Hingorani says that they were careful not to box contributions into narrow categories or definitively state a certain essay is about race or gender. They organized the anthology into wide-ranging sections: “What We Inherit,” “What We Endure,” “How We Speak,'' “How We Identify” and “How We Find Joy.” Even within the sections, there is diversity in the writers’ experiences, as they come from different backgrounds, speak different languages and have different perspectives.

Indian women’s experiences have so much dimension to them—we grapple with colonial pasts, gendered expectations, complex relationships with the idea of family, and so much more. -Shailey Hingorani

Ultimately, the editors were looking for essays that documented Indian experiences in Singapore that many might not be familiar with—stories that toyed with the boundaries of CMIO (Chinese, Malay, Indian or Other) and voiced the nonconforming or “taboo” parts of being an Indian woman out loud.

We hope that Indian women are able to find solidarity through What We Inherit, and are able to see that their personal experiences can be a profound avenue for advocacy and change. -Shailey Hingorani

Hingorani wants readers to approach the book with an open mind and recognize that everyone’s story has some nuance. She hopes that through the book, readers start noticing the inequalities around them.

I hope they recognize that we aren’t taught to be explicitly anti-racist in this society, nor are we are trained to see how seemingly un-racist policies can produce racist outcomes. These perspectives take time and effort, including the ability to see past our own prejudices. -Shailey Hingorani

Samiha Hossain (she/her) is a student at the University of Ottawa. She has experience working with survivors of sexual violence in her community, as well as conducting research on gender-based violence. A lot of her time is spent learning about and critically engaging with intersectional feminism, transformative justice and disability justice.

Samiha firmly believes in the power of connecting with people and listening to their stories to create solidarity and heal as a community. She refuses to let anyone thwart her imagination when it comes to envisioning a radically different future full of care webs, nurturance and collective liberation.