Essay: “How Much is a Little Girl Worth?"

Teach girls that their anger is a valuable weapon in defying, disobeying, and disrupting patriarchy

USA gymnasts Simone Biles (left) and Aly Raisman at the Rio Olympics. ROBERT DEUTSCH, USA TODAY SPORTS

tw: sexual abuse, suicide

"How much is a little girl worth?" — Simone Biles.

The four-time Olympic gold medallist and one of the greatest athletes in the world asked that question when she testified last week before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee examining failures in the FBI's investigation into former US Gymnastics team doctor Larry Nassar, who sexually abused Biles and hundreds of other athletes.

She was quoting fellow gymnast Rachel Denhollander, the first woman to publicly accuse him of abuse and who asked “How much is a little girl worth?” in her victim impact statement during Nassar’s trial in 2019.

The answer to that question, if we are honest, is: NOTHING.

"To be clear, I blame Larry Nassar and I also blame an entire system that enabled and perpetrated his abuse," Biles said in her testimony, alongside fellow gymnasts McKayla Maroney, Aly Raisman and Maggie Nichols.

That entire system is patriarchy.

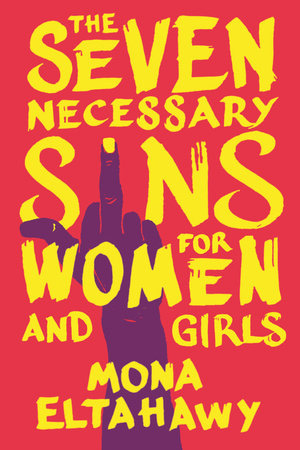

The answer to Biles’ question and my determination to destroy that entire system that enabled and perpetrated abuse are the reason I wrote my book The Seven Necessary Sins for Women and Girls, which was published in September 2019.

One day when I was four years old, a man stopped his car on the street under my family’s balcony, pulled his penis out and beckoned for me to come down. He did the same to my friend who had been talking to me from her family’s balcony across the street. I was so small that I needed a stool to see my friend from above the balcony railing.

I was enraged at that man. How dare he ruin our reverie; two little girls, happy, oblivious to the street below.

I waved my slipper at him to frighten him away. I believed I could shoo him away with just my anger. I absolutely believed in my rage, convinced that it could frighten away a grown man who had decided to stop his car underneath my balcony and wave his penis at two little girls.

I honour that angry four-year-old girl. I honour her belief that she deserved to be free of molestation and free of interruption. She was born with a pilot light of anger, tenacious and sure of its right to flare whenever treated unjustly.

I believe all girls are born with that pilot light of anger. What happens to it as they grow into women?

I want to bottle-feed rage to every baby girl so that it fortifies her bones and muscles. I want her to flex and feel the power growing inside her as she herself grows from a child into a young woman.

What would the world look like if girls were taught they were volcanoes, whose eruptions were a thing of beauty, a power to behold and a force not to be trifled with? What if instead of breaking their wildness like a rancher tames a bronco, we taught girls the importance and power of being dangerous?

What if we nurtured and encouraged the expression of anger in girls the same way we encouraged reading skills: as necessary for their navigation of the world? Imagine a girl justifiably enraged at her mistreatment. Imagine if we acknowledged her justifiable anger so that a girl understood she would be heard if anyone abused her and that her anger was just as important a trait as honesty. What kind of woman would such a girl grow up to be?

Aly Raisman, Simone Biles, McKayla Maroney and Maggie Nichols after testifying at a Senate Judiciary hearing about the Inspector General's report on the FBI's handling of the Larry Nassar investigation on Capitol Hill, Wednesday, Sept. 15, 2021, in Washington. (Saul Loeb/Pool via AP)

We must teach girls that their anger is a valuable weapon in defying, disobeying, and disrupting patriarchy, which pummels and kills the anger out of girls. It socializes them to acquiesce and to be compliant, because obedient girls grow up to become obedient foot-soldiers of the patriarchy. They grow up to internalize its rules, which are used to police other women who disobey.

From a very young age girls around the world are told that they are vulnerable and weak. By the age of 10, research shows they believe it. Conversely, boys are fed the stereotype that they are strong and independent.

From a very young age, girls are socialized, taught, and have it hammered into their consciousness that men and boys have a right to our attention, our affection, our time, and more. The child who demands her mother’s or an adult’s attention, barging into their conversations and turning the adults’ heads to see the child, is taught not to interrupt the grown-ups. But the courtesy is rarely returned, especially to girls.

What would the world look like if girls were taught they were volcanoes, whose eruptions were a thing of beauty, a power to behold and a force not to be trifled with? What if instead of breaking their wildness like a rancher tames a bronco, we taught girls the importance and power of being dangerous?

One of the biggest indictments of just how worthless girls and their words are came during the trial for Nassar, when more than 150 women and girls came forward to accuse the doctor of abuse, beginning in 2015. One of the most moving witness testimonies came from Kyle Stephens.

When Kyle told her parents at age twelve that Nassar had been abusing her since she was six, they not only did not believe her, but they made her apologize to her predator who had persuaded them that Kyle was lying, the Washington Post reported. Stephens believes that her father’s suicide in 2016 was motivated in part because of guilt at not believing his daughter. Again and again, news reports told us that parents believed Nassar the predator over their own daughters.

Imagine the damage done to those girls’ sense of truth and justice, and to their sense of trust. Imagine their sense of betrayal that the people closest to them, those very same people who are supposed to protect them, were the very same people who believed the predator over their daughters. It was on clear display when Simone Biles and other teammates testified last week.

Confronting Nassar as adults during his trial, the women gave heart-smashing testimonies, often with their parents crying in the courtroom with them. The anger and the sense of betrayal that their parents had sided with their abuser against them reminded me of Egyptian feminist Nawal El Saadawi’s description of her genital cutting at the age of six—the age Kyle Stephens was when Nassar began sexually abusing her. “I just wept, and called out to my mother for help. But the worst shock of all was when I looked around and found her standing by my side . . . right in the midst of these strangers, talking to them and smiling at them, as though they had not participated in slaughtering her daughter just a few moments ago,” El Saadawi writes.

Witness the variety of ways patriarchy enlists parents in different forms of “slaughter” of girls.

All girls are punished for behavior considered “unfeminine,” but a racist society that neglects and mistreats Black girls and which denies them their girlhood also punishes them when they react with justifiable anger at their mistreatment.

While girls everywhere face the brunt of patriarchy, when patriarchy marries with other forms of oppression, it becomes particularly brutal. The more marginalized you are, the sharper the blows of patriarchy and its attendant oppressions. In the US, gendered racism means that the victims who accused the singer R. Kelly of sexual assault were mostly ignored because they were Black women and girls.

Unlike the famous and privileged white women who accused the movie producer Harvey Weinstein of sexual assault, who were interviewed and invited to write opinion pieces—all those things take courage, and I salute those women who spoke out—the victims of R. Kelly, many of whom were teenage girls, were rarely sought out by the media. There are many grassroots activists who have been working to advance the rights of women and girls of color, such as Tarana Burke, who first used #MeToo in 2006.

According to a study published in 2017 by Georgetown Law’s Center on Poverty and Inequality, as early as age five, young Black girls in the United States of America are viewed less as children and more like adults when it comes to discipline in schools. All girls are punished for behavior considered “unfeminine,” but a racist society that neglects and mistreats Black girls and which denies them their girlhood also punishes them when they react with justifiable anger at their mistreatment.

“If our public systems, such as schools and the juvenile justice system, view black girls as older and less innocent, they may be targeted for unfair treatment in ways that effectively erase their childhood,” Rebecca Epstein, lead author of the report and executive director of the Center on Poverty and Inequality, told CNN.

How else to react but with anger when you are dealt the double blow of racism and misogyny?

“Perhaps you have figured it out by now, but little girls don’t stay little forever…They grow into strong women that return to destroy your world.”

A judge sentenced Nassar to over 300 years in jail for sexual assault. But who will hold accountable the patriarchy that not only enables and protects a predator for years but also persuades parents to believe a predator over their own daughters? How does a girl recover and heal from such betrayal?

Who will hold accountable a racist patriarchy that pays no attention to the years of abuse of teenage girls by a famous and powerful man because the girls are Black and because the gendered racism of American society reserves its most forceful cruelty for Black girls?

Who will hold accountable a patriarchy that insists on cutting off completely healthy body parts of hundreds of thousands of girls around the world in the name of “culture,” sometimes in the name of religion, but always with the goal of controlling female sexuality?

“Perhaps you have figured it out by now, but little girls don’t stay little forever,” Kyle Stephens told Larry Nassar. “They grow into strong women that return to destroy your world.”

I want a world where little girls are believed by their parents. I want a world where little girls don’t have to wait until they are women to destroy their predator’s world. What would that world look like?

I want girls to grow up with their pilot light of anger tenacious and sure of its right to flare whenever treated unjustly.

I want girls to grow up knowing that angry women are free women.

During the days of witness testimonies at Nassar’s sentencing, as women gave voice to years of trauma and betrayal, the feminist and author Ursula K. Le Guin died. Her commencement speech at the women’s college Bryn Mawr in 1986 gives us a road map to what that world would look like when girls are believed, in which girls believe they have the power to destroy their predators.

“We are volcanoes. When we women offer our experience as our truth, as human truth, all the maps change. There are new mountains. That’s what I want—to hear you erupting. You young Mount St. Helenses who don’t know the power in you—I want to hear you,” Le Guin told the young women preparing to graduate.

We must teach girls to erupt!

Girls are born with plenty of rage already, but we squash it. They are taught to be polite, to be well-behaved, and to not make a scene. We tell them not to raise their voice and not to speak too much. And if, after all of that, they still manage to simply say they wish to be free of sexual abuse, a worse silencing happens: their own parents don’t believe them, or their parents partake in the mutilation of their own daughters, ostensibly to protect them from sexual desire.

I want to bottle-feed rage to every baby girl so that it fortifies her bones and muscles. I want her to flex and feel the power growing inside her as she herself grows from a child into a young woman. I want girls to grow up with their pilot light of anger tenacious and sure of its right to flare whenever treated unjustly.

I want girls to grow up knowing that angry women are free women.

Mona Eltahawy is a feminist author, commentator and disruptor of patriarchy. Her first book Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution (2015) targeted patriarchy in the Middle East and North Africa and her second The Seven Necessary Sins For Women and Girls (2019) took her disruption worldwide. It is now available in Ireland and the UK. Her commentary has appeared in media around the world and she makes video essays and writes a newsletter as FEMINIST GIANT.

FEMINIST GIANT Newsletter will always be free because I want it to be accessible to all. If you choose a paid subscriptions - thank you! I appreciate your support. If you like this piece and you want to further support my writing, you can like/comment below, forward this article to others, get a paid subscription if you don’t already have one or send a gift subscription to someone else today.