Posters of support placed by neighbours outside the Idris mosque, Seattle. (Photo by Julia-Grace Sanders)

The day after the September 11, 2001 attacks, we did not leave the apartment because we were worried that Americans angry at Muslims would attack my sister-in-law, who wore a hijab. I lived in Seattle at the time and my brother and his wife were visiting me and my (now ex) husband.

Two days after 9/11, one such angry American tried to start a fire in my local mosque’s parking lot. When two Muslims coming out from night prayers inside the Idris mosque tried to stop him, the man– who was drunk – tried to shoot them; he missed, then jumped into his car and drove into a tree.

When we heard what had happened, we drove to the mosque and were moved to see flowers and messages of support already flooding its entrance. And from that night on and for weeks more, neighborhood men and women holding signs that read “Muslims are Americans” stood on 24-hour guard outside the mosque.

Compassion was not one-sided. Issa Qandil, a Jordanian immigrant to the United States of Palestinian descent, who was one of the two Muslim men the would-be arsonist had tried to shoot, told authorities that he wanted to drop the charges because he believed that forgiveness is a way to get closer to God.

Qandil visited the man in jail and told him that he understood why he did what he did and that he forgave him. Qandil even testified at his sentencing hearing, saying that retribution was useless and asked the court to be lenient. The defendant got six-and-a-half years instead of 75. He wrote a four-page, handwritten apology to the mosque in which he referred to “the two brave men of your congregation.” The attempted attack on the mosque in Seattle ended without harm but other attacks were successful.

Two weeks after 9/11, a group of young men asked the white American husband of a Pakistani-American woman I knew "What's it like to fuck a terrorist?"

Two months after 9/11, a special agent with the FBI went to my brother’s home in the Midwest to ask him if he “knew anyone who had celebrated the attacks.”

A year after 9/11, I left my husband. Not because he was an American and I an Egyptian, nothing to do with culture or religion; nothing to do with 9/11. We brought out the worst in each other.

A year before 9/11, he was the reason I had moved to the United States, a country that had never been more than distant vacation memories. When I signed my divorce papers, I packed for a new job and life in New York City and I got into my car to drive there. For 18 days – just America and me. And paranoia: just before I left, a group of Muslim men had been stopped on the highway. Apparently, a customer at a diner they’d just frequented had heard them speaking Arabic (not sure how she knew it was Arabic as most Americans wouldn’t distinguish it from Swahili, say) and called the police, saying they were acting “suspiciously.”

My brother is a cardiologist in a country that refuses to stand still and allow its heart to heal, choosing revenge and mass destruction instead. My sister-in-law delivers babies in a country whose exceptionalism will not allow it to birth a better version of itself.

A year and five months after 9/11, I began a relationship with a Black American man in New York City. We lived together for three years during which we boycotted the Arab-owned bodega in our Manhattan neighbourhood because of the racism of the men behind the counters. I am often assumed to be Latinx. The Arab men in the bodega did not think I spoke Arabic nor that I understood the ugly things they were saying about Marcus. I confronted them in rage at the fuckery of being Muslims who were anti-Black in New York City at a time when Muslims were being subjected to the fuckery of profiling.

Muslim Americans were not invented on September 11, 2001. Our history with New York, and the rest of the country for that matter, far precedes those attacks. Some of the earliest arrivals were on slave ships that crossed the Atlantic. For many non-Black Muslims, 9/11 forced an uncomfortable and dangerous visibility. Black Muslims have been there all along, confronting racism--including from fellow non-Black Muslims--and Islamophobia, years before 9/11.

I spray painted over that fucking ad because I was fed up of the bullying and vilification of American Muslims. I spray painted over that fucking ad for my niblings. They will not grow up to be scared or apologetic for being Muslim, or Egyptian, or brown.

A year and a half after 9/11, while he and my sister-in-law were expecting their first child, my brother had to submit to “special registration,” as part of the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System (NSEERS) that the Bush administration enacted on September 10, 2002. He was photographed, finger-printed and interrogated for the database which would go on to register and monitor more than 80,000 Muslim and Arab men and boys. More than 13,000 of those registrants were placed in deportation proceedings. Special registration was aimed at temporary foreign visitors who present "increased national security concerns."

The day of 9/11, as we watched the twin towers crumble on live television, I told my brother and sister-in-law, “If this is Muslims, they’re going to round us up and put us in camps.”

Fifty-nine years before 9/11, shortly after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the U.S. held people of Japanese descent, including U.S. citizens, in concentration camps. And now here they were creating a database, using powers to survey, detain, and to deport. And to fill a prison camp in Guantanamo with Muslim men who had not been charged or tried.

A decade after 9/11, President Barack Obama’s administration suspended NSEERS. More than 15 years after 9/11, it ended the programme, which had not resulted in a single terrorism conviction.

For many non-Black Muslims, 9/11 forced an uncomfortable and dangerous visibility. Black Muslims have been there all along, confronting racism--including from fellow non-Black Muslims--and Islamophobia, years before 9/11.

A year and nine months and two weeks after 9/11, my brother and his wife had their first child, a daughter--the first American in our family.

Eleven years after 9/11, when she was nine years old, she and her brother who had turned six just five days earlier, and their siblings--twins who were four years old-- were in their local mosque in a swing state in the Midwest for Sunday school just hours before a man set the building on fire. Eleven years after the failed arson attempt at my local mosque in Seattle, an Islamophobic white supremacist had succeeded in arson hundreds of miles away, gutting my brother’s local mosque in the Midwest.

Thirty eight years before 9/11, the bombing of Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, killed four young Black girls who had just got out of Bible class.

“I had it in my mind to go out and kill someone,” Nina Simone said about her reaction. “I didn’t yet know who, but someone I could identify as being in the way of my people.” It took her an hour to write “Mississippi Goddam.”

Alabama’s got me so upset

Tennessee makes me lose my rest

And everybody knows about Mississippi Goddam!

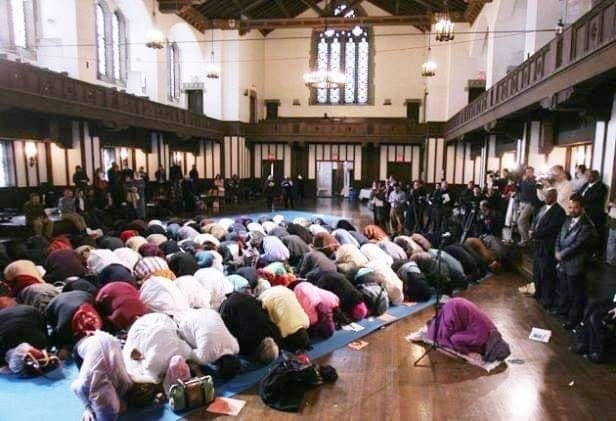

Three and a half years after 9/11, a Black American feminist scholar of Islam called Dr. Amina Wadud became the first woman imam to lead a mixed-gender Friday congregational prayer--100 of us--50 women and 50 men. It was one of the most moving moments of my life. The prayer was co-sponsored by the (now defunct) Progressive Muslim Union of North America (PMUNA), of which I was a board member.

Dr. Amina Wadud leading us in a mixed-gender Friday prayer, 2005. From her Facebook page.

A jihadist website urged Osama bin Laden to issue a fatwa calling for our deaths, while the now late Libyan leader Muammar el-Qaddafi complained at the time to an Arab League summit meeting that our prayer would create a million bin Ladens. A woman leading one hundred people in prayer would inspire people to extremist violence, rather than than oppression, torture and corruption of regimes such as those led by Qaddafi and his fellow dictators at that Arab League summit.

A BBC documentary filmmaker told me that during his interview soon after our prayer with Iraqi cleric Muqtader al-Sadr - usually described as “hardline” and “fiery” in western media - he asked Sadr what was the worst thing the US had done. Remember, my reader, that Amina Wadud had led us in prayer in New York City in 2005, two years after the US invaded al-Sadr’s country Iraq, in its war of revenge--along with the war on Afghanistan-- for 9/11, leading directly or indirectly to the deaths of almost half a million Iraqi citizens. Sadr replied “Allow a woman to lead prayer.”

The PMUNA had come to be in the aftermath of 9/11, as part of the vigorous internal Muslim arguments and debates those awful attacks had shaken into being. Remember: al-Qaeda has killed more Muslims than non-Muslims. No mosque would host our female-led mixed-gender prayer. An art gallery that had agreed backed out after a threat. The Cathedral of St. John the Divine kindly offered us a lay building on its premises for our prayer.

Fifty-nine years before 9/11, shortly after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the U.S. held people of Japanese descent, including U.S. citizens, in concentration camps. And now here they were creating a database, using powers to survey, detain, and to deport. And to fill a prison camp in Guantanamo with Muslim men who had not been charged or tried.

Four years after 9/11, my brother and sister-in-law moved to a small town in the Midwest--population 8,200--where she had just been hired as the sole female OB/GYN physician. They were the only Muslim family in the entire town. One day she and I were watching one of those medical dramas when she told me this: "I was delivering a baby the other day and the father was watching via Skype cam. He was a soldier in Afghanistan. And I thought, here I am: a Muslim doctor in a headscarf delivering a baby whose father is an American soldier in Afghanistan, a Muslim country."

Eleven years after 9/11, and on my nephews’ sixth birthday, I was arrested in New York City for spray painting over a racist and bigoted pro-Israel ad. I realized as I was handing my possessions over in the transit police holding cell that I had not yet called my nephew to wish him a Happy Birthday.

A member of the American Freedom Defense Initiative, which paid for the ad campaign, trying to stop me from spray painting over it. Photo by Kristy Leibowitz

Five days later, the arsonist set my brother’s local mosque on fire. It was a coincidental correlation. My brother and his family had been living in a larger town where they were no longer the only Muslim family but hate cannot be contained. The through line was Islamophobia and ultimately racism. From the ad that I defaced which equated Muslims and Palestinians with “savages,” to the arsonist who said he set my brother’s local mosque on fire because he’d seen on Fox News that “Muslims are killing Americans abroad.” From the arson attacks against mosques since 9/11 to the bombings of Black churches. From a database of Muslims and detentions without trial to the internment of Japanese Americans.

I spray painted over that fucking ad because I was fed up of the bullying and vilification of American Muslims. I spray painted over that fucking ad for my niblings. They will not grow up to be scared or apologetic for being Muslim, or Egyptian, or brown. They will not grow up feeling they should apologise for something they had nothing to do with and they will not grow up hiding any part of their identities or having to choose one identity over the other.

Twenty years after 9/11, On the 20th anniversary of that day, my eldest niece who has just moved to dorms to start university, texted her dad, my brother this: “bruh can you guys send me my liverpool kit lol these bozos like man u and other teams and I have to rep.”

In my family of Liverpool supporters, I am the only one who supports Manchester United. Nevertheless, when my brother shared my niece’s text with our family WhatsApp group, it was a relief. The days leading up to every 9/11 anniversary are always heavy with trauma--20 years worth of it.

My brother is a cardiologist in a country that refuses to stand still and allow its heart to heal, choosing revenge and mass destruction instead. My sister-in-law delivers babies in a country whose exceptionalism will not allow it to birth a better version of itself.

And so we are forever the day after 9/11.

Mona Eltahawy is a feminist author, commentator and disruptor of patriarchy. Her first book Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution (2015) targeted patriarchy in the Middle East and North Africa and her second The Seven Necessary Sins For Women and Girls (2019) took her disruption worldwide. It is now available in Ireland and the UK. Her commentary has appeared in media around the world and she makes video essays and writes a newsletter as FEMINIST GIANT.

FEMINIST GIANT Newsletter will always be free because I want it to be accessible to all. If you choose a paid subscriptions - thank you! I appreciate your support. If you like this piece and you want to further support my writing, you can like/comment below, forward this article to others, get a paid subscription if you don’t already have one or send a gift subscription to someone else today.

Thank you. Excellent article.