The Menopause: When We Are Free

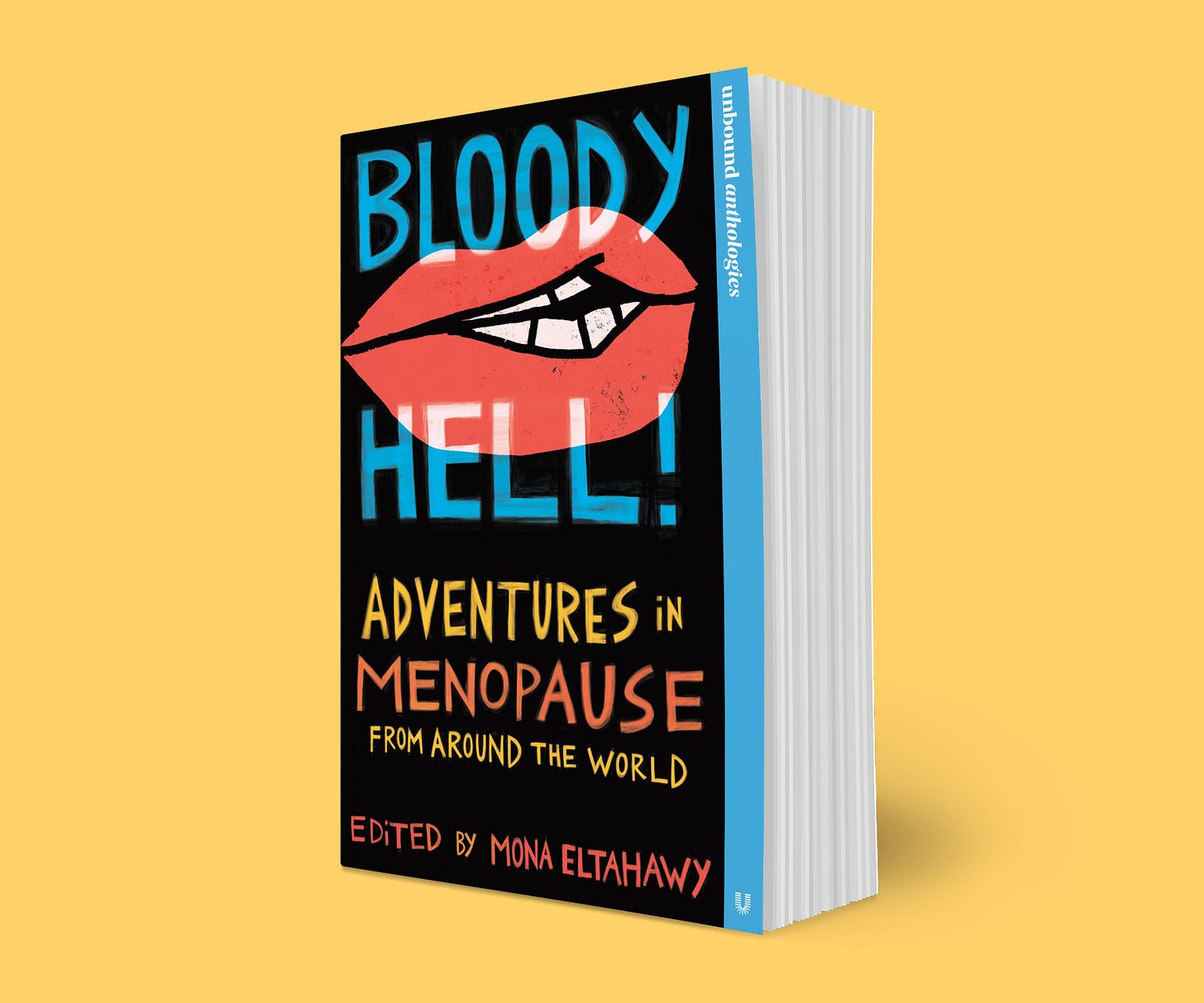

Excerpt from Bloody Hell! Adventures in Menopause from Around the World

Excerpt from Bloody Hell! Adventures in Menopause from Around the World

By Marilyn Muthoni Kamuru

When we are free, what will we do with our freedom?

Almost two decades ago, when my aunt was in her fifties, she decided to move to America. She had always lived in Kenya. A few years before, she had retired from her job, where she had been making a comfortable living. She was still married and all of her children had left home. My aunt’s decision wasn’t particularly unusual. Families and communities around the continent have similar stories of women who left in their forties, fifties and even sixties. An exodus of African women departing for Europe and the United States. Often this happened after the marriage of a child, or the birth of a grandchild. Yes, these women were interested in economic opportunities, but there was something else driving them. There were aunties leaving to attend a wedding or grandmothers going on the pretext of helping the new mother and ensuring the grandchild ate the ‘proper food’ and spoke a few words of Kikuyu, Kisii or Kiswahili. Just a visit. Some of these aunties and grandmothers were going abroad for the first time, others had visited before, but what we didn’t know at the time of their departure is that this time they wouldn’t be coming back. I am not sure they all knew it either.

I am about the age my aunt was when she moved to the US almost twenty years ago. When I was discussing this phenomenon with my girlfriends, we spoke about these as silent divorces, about women escaping, in a socially acceptable way, their unhappy or unsatisfactory familial situations. Women whose age and socialisation wouldn’t allow them to get a divorce. And maybe some of that is true, but I don’t think it is the whole truth. I don’t think women are running away as much as they are running to.

Women in the menopause transition are encouraged to think of ourselves as socially useless, used up. But it is what women are doing with this social irrelevance that is threatening the patriarchy. The women who travel abroad are a subset of the women who in social irrelevance find permission and freedom to be. In the social irrelevance that is supposed to accompany women when they stop bearing children, women have found opportunities to feel their own desires and to create their own relevance without reference to societal expectations. Less making lemonade with lemons, and more pass the tequila and salt. The narrative most of these women have of the menopause transition isn’t one that is dominated by the patriarchy’s position on the value of women in the menopause, nor by their menopausal symptoms. As Dr Jen Gunter aptly states in her book The Menopause Manifesto: Own Your Health with Facts and Feminism, ‘What the patriarchy thinks of menopause is irrelevant. Men do not get to define the value of women at any age.’ Instead, the narrative that seems to prevail among these African aunties is of a more feminist menopause, a phase of life that is fundamentally about freedom – women’s freedom. Freedom from and, more importantly, freedom to. This narrative of the menopause transition is particularly problematic for the patriarchy.

What we are witnessing with the exodus of African women abroad in their late forties and fifties is an expression of this narrative of the menopause as freedom.

Women in the menopause transition are encouraged to think of ourselves as socially useless, used up. But it is what women are doing with this social irrelevance that is threatening the patriarchy.

So much of what we are encouraged to focus on with the menopause transition is what ceases, what stops happening. The loudest menopause narratives are about who we stop being – women who can reproduce. The cessation of menstrual periods and the end of the reproductive phase. It is the biology of menopause and the resulting societal implications that we are encouraged to focus on. Indeed, even the purpose of menopause is explained by its evolutionary benefit to others, from the ‘mother hypothesis’, which holds that older mothers benefit more from investing in their current children rather than in continuing to reproduce themselves, to the ‘grandmother hypothesis’, which argues that grandmothers have a benefit to the reproductive success of their children and improve the survival and wellbeing of their grandchildren. What doesn’t seem to get anywhere near as much attention is what is the meaning of the menopause for women. In other words, what does it mean for a woman to live through perimenopause, menopause and into postmenopause? What do these phases (which for this piece I will refer to broadly as the menopause or the menopause transition) mean for her life? For our lives? What continues flowing? Somehow, even in this uniquely female life process – and it is a process, not an event – women and women’s lives have become incidental. While recognising that it is all people with ovaries who experience menopause, I will use the term ‘women’ in this piece because I am more concerned with the gendered social and societal implications of the menopause transition as opposed to the physical biological process.

For many African women, the menopause transition is a time of freedom. A time when patriarchy no longer cares, when it is focused on the women in their pre-reproductive and reproductive stages, and then we are free.

MODERN MENOPAUSE

At the same time as our African aunties are choosing to cross continents, we are witnessing other African aunties, in the menopausal transition, reach for some of their most career transgressive and ambitious public roles. Ellen Johnson Sirleaf was fifty-nine when she first ran for president and sixty-seven when she was elected President of Liberia. Joyce Banda was sixty-two when she was elected President of Malawi, and Samia Suluhu Hassan was sixty-one when she assumed the presidency of Tanzania. In Kenya, Charity Ngilu and Professor Wangarĩ Maathai were the first two women to vie for president in 1997, and they were forty-five and fiftyseven years old respectively. In 2021 Kenya got its first woman Chief Justice; at the time of her appointment, Martha Koome was sixty-one years old. Martha Karua, the first female deputy presidential candidate of a leading political party in Kenya, was fifty-six when she unsuccessfully ran for the presidency in 2013. In 2004, at the age of sixty-four, Professor Wangarĩ Maathai was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. And seven years later, in 2011, the same prize was jointly awarded to President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, then seventythree, and fellow Liberian Leymah Gbowee, thirty-eight.

The experiences of these African women, from aunties to presidents and Nobel Prize laureates, are manifestations of the power of the menopause-transition narrative. Yes, they are a result of the opportunities now available to women, but which opportunities women seize is dependent on the menopause narrative they adopt.

For many African women, the menopause transition is a time of freedom. A time when patriarchy no longer cares, when it is focused on the women in their pre-reproductive and reproductive stages, and then we are free.

Bloody Hell: Adventures in Menopause from Around the World is published by Unbound available to order now as paperback and e-book

Mona Eltahawy is a feminist author, commentator and disruptor of patriarchy. Her new book, an anthology on menopause called Bloody Hell!: Adventures in Menopause from Around the World, has just been published. Her first book Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution (2015) targeted patriarchy in the Middle East and North Africa and her second The Seven Necessary Sins For Women and Girls (2019) took her disruption worldwide. It is now available in Ireland and the UK. Her commentary has appeared in media around the world and she makes video essays and writes a newsletter as FEMINIST GIANT.

I appreciate your support. If you like this piece and you want to further support my writing, you can like/comment below, forward this article to others, or send a gift subscription to someone else today.